The case for indigenous knowledge systems and knowledge sovereignty (part 1): Introduction

This article is part 1 of a series of articles putting forward the case for indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) and knowledge sovereignty, featuring selected excerpts from the book Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders.

In previous RealKM Magazine articles, I’ve argued that there’s a need for an improved awareness of cultural differences in knowledge management.

One aspect of the cultural differences in knowledge management are the differences between indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) and scientific / western knowledge systems. As Dr Zeremariam Fre from University College London (UCL), argues in a new open access book:

Our perception of knowledge and reality is, in part, culturally, socially and ecologically determined, and that applies to a multitude of indigenous, or local/empirical, and exogenous, or scientific/western, knowledge systems, including indigenous pastoralist knowledge systems in the African drylands. Knowledge systems, in general, are based on the observation, assumption and interpretation of complex realities. They can be defined as organised structures and dynamic processes of a cluster of understandings, usually locally specifc, or both.

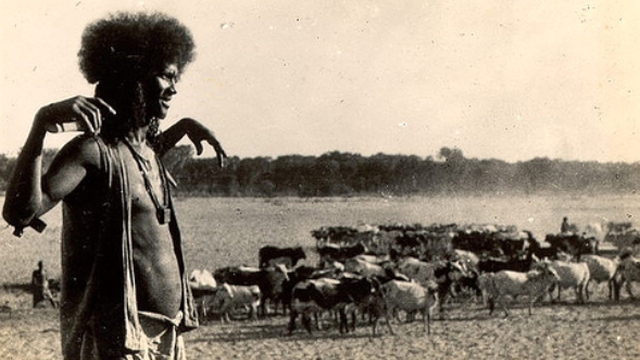

In the book, titled Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders, Fre argues the case for indigenous knowledge systems and knowledge sovereignty, drawing on the example of Africa’s Beni-Amer people:

In a world in which the sustainability of industrial agriculture is being seriously questioned, there is growing evidence that bio-cultural knowledge systems and practices offer greater opportunities for environmentally and socially just sustainable food production and food sovereignty. I believe that the solution lies in identifying and exploring new epistemic and practical connections between culturally and politically distinct indigenous and exogenous knowledge systems from a complementarity perspective. Thus, the arguments about sustainable food production and food sovereignty need to be strongly anchored in the knowledge sovereignty of the so-called poor and dispossessed, because the worst dispossession is to not acknowledge such sovereignty.

Indigenous knowledge systems are the strategies communities employ to deal with everyday issues such as food production, health, education and the environment.

In the coming weeks, we’ll be featuring selected excerpts from Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders in a series of articles:

Part 1: Introduction (this article)

Part 1: Introduction (this article)

Part 2: The broader context

Part 3: The ‘indigenous’ versus the ‘scientific’ position

Part 4: Advancing the cause of knowledge sovereignty

Part 5: Threats to indigenous knowledge and knowledge sovereignty

Part 6: Key debates

Part 7: Hybrid knowledge systems: are they feasible

Part 8: Knowledge sovereignty: threats, adaptation and merger

Part 9: Knowledge systems of the Beni-Amer

Part 10: Moving the debate forward

Part 11: Policy and research recommendations

Part 12: Reflections on ways forward

Next part (part 2): The broader context.

Article source: Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Header image source: Tigre man from Barka Valley is in the Public Domain. The Beni-Amer people probably emerged in the fourteenth century AD from the intermixing of the Beja and the Tigre.

See also: Cultural awareness in KM.