The case for indigenous knowledge systems and knowledge sovereignty (part 8): Knowledge sovereignty: threats, adaptation and merger

This article is part 8 of a series of articles putting forward the case for indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) and knowledge sovereignty, featuring selected excerpts from the book Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders.

The recognition and use of indigenous knowledge (IK), not only as a system in itself but also as a response to other knowledge systems, are under threat from an array of angles: physical, economic, political, and even academic. However, it is in the face of these threats that IK has demonstrated its resilience.

Berkes and Jolly1, for instance, have studied a community in the Canadian Western Arctic who, despite stresses brought by climate change, still employ their traditional knowledge system and practices related to hunting and fishing to obtain much of the protein they require in their diet.

Davies and Bennett2 document the resilience faced by pastoralists as they cope with both economic and political pressures such as the ‘loss of valuable resource patches to agricultural projects, and the growing restriction in access to the natural resource base’. They point out that despite, and even in answer to, these new sources of pressure and insecurity, traditional risk management strategies, such as herd management and the maintenance of strong social bonds, remain. The production of butter gives them a source of capital that is not only more liquid than cattle, but also easily stored and sold. Among the Afar communities in Ethiopia, ‘the ability to produce butter enables Afar households to benefit from periodic gluts, although this is limited by human capital constraints (labour and also knowledge of new or improved processing techniques)’. Strong social bonds are also created and maintained, partly through a debt system which requires the gifting of anything from services to livestock in times of need. This particular risk management strategy not only helps to ensure a more egalitarian society, but also creates a form of bonding capital within the society.

There is ample evidence that IK responds, and adapts itself, to new situations and imperatives in order to service the community that uses it. It is not in simple adaptation, however, that we see the true strength of IK, but rather in IK’s ability and willingness to adopt principles and practices from other systems of knowledge. This ability to extract information and practices from elsewhere and incorporate them into one’s own knowledge system, that is, the power to use one’s own system of knowledge to evaluate an integral component of another knowledge system and pronounce it worthy or unworthy of incorporation into one’s own repertoire of knowledge and practice, is one of the quintessential expressions of knowledge sovereignty.

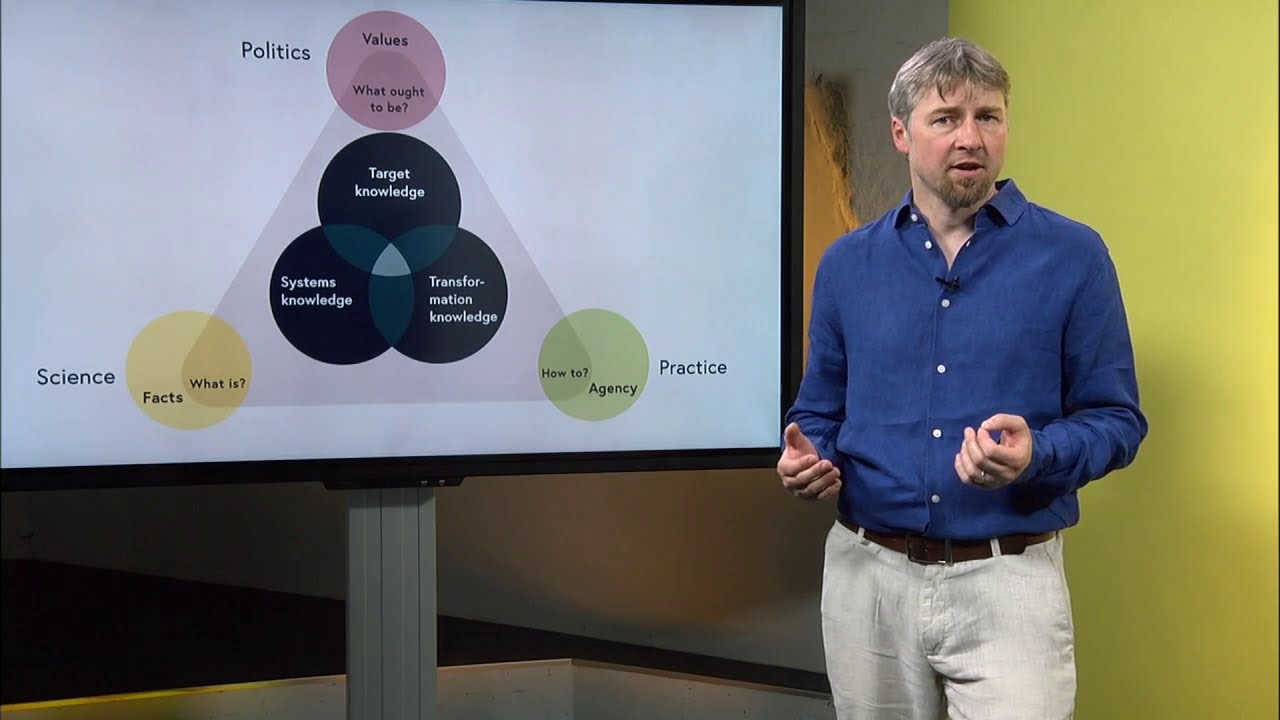

It is of great importance to note that implicit in the concept of a merger of knowledge systems is the idea that neither on its own is infallible or complete. In discussing the possibility of combining knowledge systems in some way, or even perhaps the need to do so, one recognises the limitations of each in addressing current needs in a satisfactory manner.

In his 1994 article3, DeWalt explains in detail the difficulties of such a merge in knowledge systems, elucidating the deficiencies inherent in each, and the benefit which could be felt if ‘more effective and creative interactions between [them]’ could be achieved. One of the deficiencies of occidental knowledge construction, according to DeWalt, is that although it is extremely adept at breaking phenomena into researchable pieces, the result of doing this is that ‘complex systems and those characterized by myriad interactions are likely to be ignored’. This is a critique mirrored by Scrinis in his 2013 work Nutritionism4, in which he criticises the modern medical and health establishment for reducing the concept of nutrition to a smattering of individual vitamins, minerals and other elements, resulting in the inference that they act independently rather than working with each other to create on overall nutrition profile. This tendency to ignore the interactions between various studied elements in a complex system, states DeWalt, has facilitated an academic and political environment in which scientists are given licence to ‘advocate the change of one part of the system without paying attention to the results for the overall system’. Furthermore, [according to DeWalt,] the institutionalisation of occidental knowledge creation has led to a sense of disconnect between its practitioners and those upon whom this knowledge acts, leading to the assertion that this knowledge is ‘value-free, disconnected from the ethical, social, or ecological consequences of their research’.

Indigenous knowledge systems (IKS), on the other hand, apart from their proclivity to be too highly (and naively) valorised by some, have the unfortunate shortcoming of being definitively local. Whereas occidental knowledge claims to be universally applicable, IK is very much a product of its surroundings, and the knowledge gained in one geographical region may be wholly useless in another. This is what Latour5 called ‘mutable immobiles’, that is, changeable, relational knowledge which is attuned to one particular location. Given the increasingly global and interconnected world, such immobile knowledge is certainly facing an existential crisis, despite whatever resilience it may have demonstrated.

In addition to these systemic differences, a true merger of knowledge systems is often considerably hampered by the practicalities of life in many places. Lumu, Katongole, Nambi-Kasozi et al.6 explore the choices in feed made by livestock farmers in and near Kampala, Uganda. In this work, they unearth a vast wealth of indigenous knowledge pertaining to nutrition in various feed sources, and the health impacts feed choices will have on livestock. For example, in nutrition surveys conducted among cattle farmers, brewer’s waste and elephant grass scored the highest, with smooth coats and firmer faecal droppings being the observed health benefits, while other items, such as sweet potato peels and banana peels, were rated the lowest in terms of nutrition. However, Kampala is a rapidly urbanising environment, and, as a result, ‘feed availability is a major limiting factor, and as a response, urban livestock farmers have resorted to using whatever resource is available to them, particularly food/crop wastes (market crop wastes, leftover food, etc.) and forages obtained from open access lands (roadsides, wetlands/swamps, etc.)’. This very real limitation of availability has led to banana peels (widely available from the markets) being reported as the most commonly used source of feed, despite a preference for almost anything else and an awareness ‘that the practice compromises nutritional quality’.

All of this being said, we know that such mergers of knowledge, although fraught with difficulty, are possible. Very much contrary to the notion that IK and occidental knowledge are mutually exclusive, Couix7 explains how such a merger could take place, through a study of fire prevention operations in France. According to Couix, cognitive and operational synchronisation is necessary for the successful production of a hybrid system of knowledge and its implementation in the world. ‘Cognitive synchronisation corresponds to communication processes aiming at establishing a “context of mutual knowledge” about the situation between the actors (information on the problem, envisaged solutions, hypotheses retained, etc.) as well as about the field of knowledge under question. Operational synchronisation aims at assuring task distribution among the actors and coordinating the schedule for carrying out the actions (sequence of actions, simultaneousness of certain actions, pace, etc.)’.

In the study, technical (forestry and farming representatives) and administrative partners were organised into a cohesive unit to co-design a land rehabilitation plan. As these various stakeholders were brought together, each having its own knowledge background and agendas (forestry representatives wanting increased replanting and fire watching and fighting, and farming representatives desiring the reintroduction of farming activities that facilitate the maintenance of open areas), the conversation moved from a reactive stance against fire to a more proactive one. ‘They moved, in fact, from speaking in terms of the struggle against the phenomenon to a formulation in terms of preventing the conditions which fostered the development of the phenomenon. What is more, the resulting land rehabilitation proposals were quite innovative compared to the plans previously implemented (networks of tracks, cisterns, water reserves) which sought only to allow fire to be fought efficiently’.

It was in the implementation of the co-designed project, however, that things began to crumble. There was neither coordination between the various actors nor follow-up on the original design of the plan, which inevitably led to conflict. For example, ‘at the site, the forest technician developed a project with four forest owners without taking into account the presence of the shepherd using the plots next to theirs. The shepherd in turn brought in the farm technician in hope of having the forester’s project revised according to his own interests. The farm technician intervened, however, too late and could not succeed in renegotiating a project review’. Such situations demonstrate the difficulty with which combined knowledge systems consisting of various groups (all with their own agendas) actually play out in the real world.

However, all is not in vain and some joint projects combining multiple knowledge systems do work. Aubron, Guérin, Gallion and Moulin8, for example, describe in detail how pastoral knowledge is being combined with knowledge from the field of forestry in order to construct a technical support tool for use in silvo-pastoral practices. This participatory modelling practice lies at the forefront of efforts to hybridise knowledge systems. It allows stakeholders, and not just ‘knowledge gatekeepers’, to mobilise their knowledge ‘to replace (or complement) data sets and equations produced through experimental research that often are inadequate in certain research fields’. Of more ‘real-world’ benefit is that such involvement of stakeholders necessarily produces social outputs, which helps this new joint knowledge avoid any claims to being ‘value-free’ or dissociated from its intended users.

Another programme designed to link indigenous knowledge to occidental knowledge and methodologies is described in Kristjanson et al.9. Here, a selection of interrelated research projects was devised in order to address and improve sustainable livestock practices. One of these projects specifically targeted pastoral groups. Its goal was ‘to work closely with largely marginalized pastoral communities and more effectively contribute to scientific evidence-based policies and practices (an outcome) for the sustainable use of their rangelands (a longer-term impact)’. From the outset, all actors in the project were encouraged not only to use, but to put forward, their own rubric, by which they measured project success. Such transparency from the outset not only allowed all ‘sides’ to better understand the measures of success deemed necessary for other actors, but also facilitated joint strategies to achieve these various goals.

By the end of the project, a land use map was produced jointly, whereby ‘the local community group was able to catch the attention of the policy makers and have their information and concerns included in a new land policy … The result was Kenya’s first ever land-use master plan for a pastoral area’. It is important to note that, unlike in Couix’s project, in which lack of communication in the implementation stage caused a breakdown, here the project hired community facilitators as part of the research team. Their duty was to ensure ongoing communication between the community, researchers and policy makers. ‘In this case, constant engagement essentially blurred the boundaries between researchers, policy makers and communities, increasing the probability that the information generated would not only be useful, but used’.

The [following parts of this series of articles] … will explore ways of moving this debate forward in the realms of research and policy.

Next part (part 9): Knowledge systems of the Beni-Amer.

Article source: Knowledge Sovereignty among African Cattle Herders is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

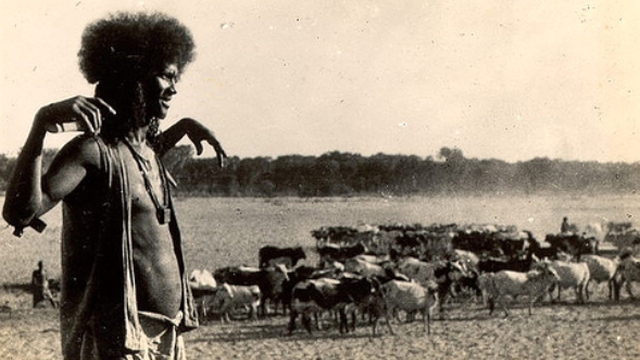

Header image source: Tigre man from Barka Valley is in the Public Domain. The Beni-Amer people probably emerged in the fourteenth century AD from the intermixing of the Beja and the Tigre.

See also: Cultural awareness in KM.

References:

- Berkes, F. and D. Jolly. 2001. ‘Adapting to Climate Change: Social-Ecological Resilience in a Canadian Western Arctic Community.’ Conservation Ecology 5 (2): art. 18. ↩

- Davies, Jonathan and Richard Bennett. 2007. ‘Livelihood Adaptation to Risk: Constraints and Opportunities for Pastoral Development in Ethiopia’s Afar Region.’ Journal of Development Studies 43 (3): 490–511. ↩

- DeWalt, Billie. 1994. ‘Using Indigenous Knowledge to Improve Agriculture and Natural Resource Management.’ Human Organization 53 (2): 123–31. ↩

- Scrinis, Gyorgy. 2013. Nutritionism: The Science and Politics of Dietary Advice. New York: Columbia University Press. ↩

- Latour, Bruno. 1986. ‘Visualization and Cognition: Thinking with Eyes and Hands.’ In Elizabeth Long and Henrika Kuklick (eds), Knowledge and Society: Studies in the Sociology of Culture Past and Present, vol. 6, 1–40. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. ↩

- Lumu, Richard, Constantine Bakyusa Katongole, Justine Nambi-Kasozi, Felix Bareeba, Magdalena Presto, Emma Ivarsson and Jan Erik Lindberg. 2013. ‘Indigenous Knowledge on the Nutritional Quality of Urban and Peri-urban Livestock Feed Resources in Kampala, Uganda.’ Tropical Animal Health and Production 45 (7): 1571–8. ↩

- Couix, Nathalie. 2002. ‘Concerted Approach to Land-Use Management: Developing Common Working Procedures. A Cevennes Case Study (France).’ Land Use Policy 19 (1): 75–90. ↩

- Aubron, Claire, Gérard Guérin, Bruno Gallion and Charles-Henri Moulin. 2013. ‘Drawing together the knowledge of forestry and pastoralism experts in the construction of a technical support tool for silvopastoralism.’ Journal of Environmental Management 117: 162–71. ↩

- Kristjanson, Patti, Robin S. Reid, Nancy Dickson, William C. Clark, Dannie Romney, Ranjitha Puskur, Susan MacMillan and Delia Grace. 2009. ‘Linking International Agricultural Research Knowledge with Action for Sustainable Development.’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (13), 5047–52. ↩