Does discomfort help to explain the effectiveness of agile and other incremental / cyclic methods?

An agile method relies upon the incremental and iterative completion of goals with a self-managing team. Reasons for the effectiveness of agile methods are widely discussed, and include being able to respond quickly to change, more readily cope with uncertainty, and better meet the needs of clients.

But what is it about agile methods that makes teams more able to do this? Rebecca Freeth and Guido Caniglia provide a potential insight in this regard in a recent post on the i2insights blog. They discuss the role of discomfort as a motivator. Discomfort may also be a similar factor in other incremental / cyclic methods such as the OODA loop (observe – orient – decide – act) and Deming wheel (plan – do – check – act).

Before exploring how discomfort might help to explain the effectiveness of agile and other incremental / cyclic methods, I’ll provide a very brief and basic introduction to agile methods for anyone unfamiliar with them or needing a refresher.

Agile methods

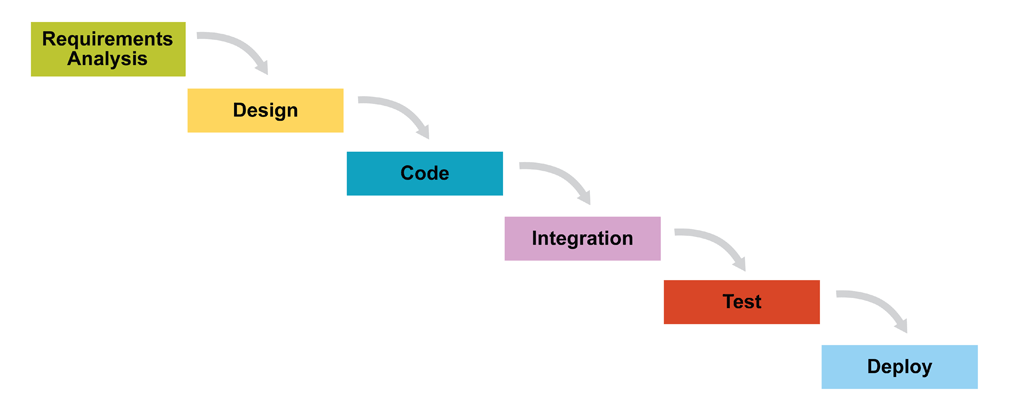

Agile methods are commonly used in software development, where the incremental and iterative process of agile methods is often presented in opposition to the “waterfall” process.

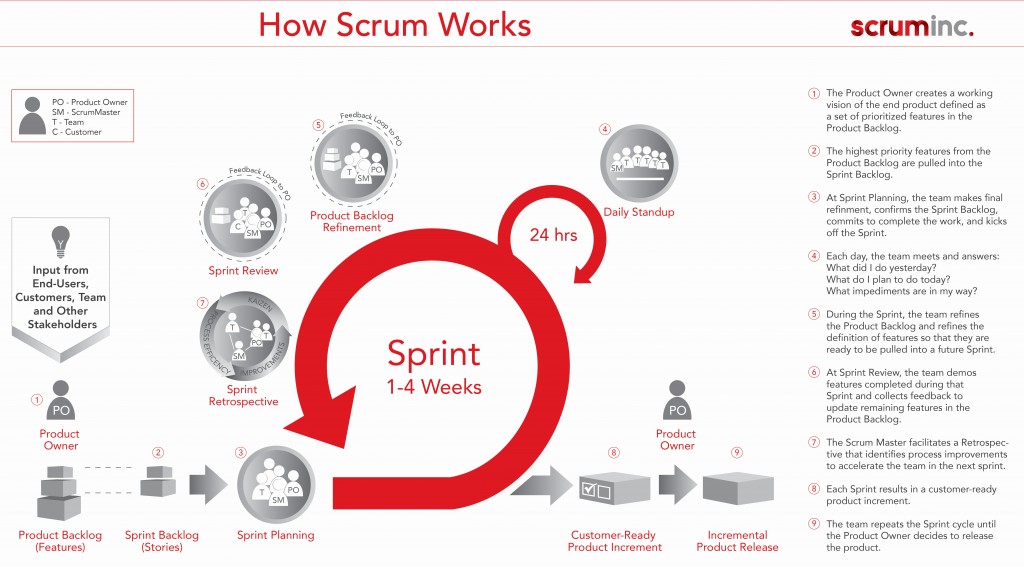

In a waterfall process (Figure 1 above), teams sequentially gather requirements, complete a design, and then build a final product. However, in an agile process such as the popular Scrum framework (Figure 2 below), work is carried out in short, iterative, and incremental cycles.

Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka proposed the core agile concept of iterative, continuous delivery in 19861. They are acknowledged2 as the inspiration for Scrum today.

Note that the term “Scrum” is often used interchangeably with “agile”. However, properly speaking, “Scrum” is a specific methodology whereas “agile” can be any technique that focuses on iterative delivery and empowerment.

Discomfort as a motivator

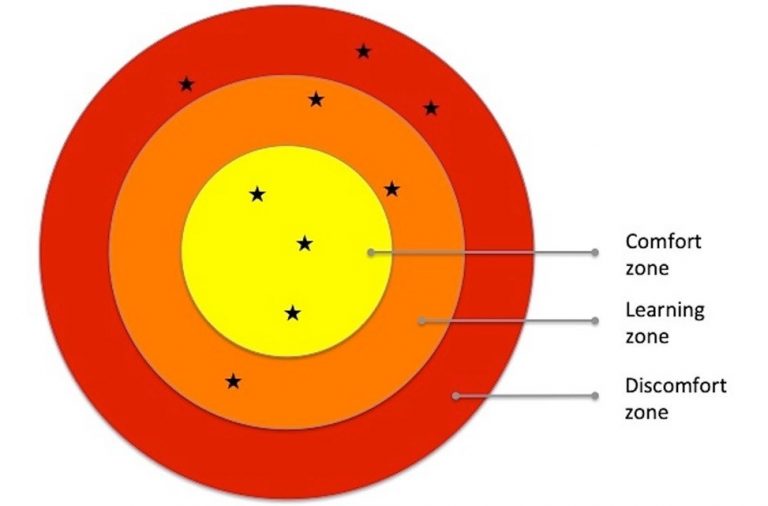

Freeth and Caniglia draw on the work of German pedagogue Tom Senninger3 to explore varying degrees of discomfort as prompts for on-the-job learning and collaboration. They advise that:

Too much discomfort and our stress levels can block learning. But with zero discomfort, there may be little stimulus to challenge one’s own assumptions. As shown in … [Figure 3 below], somewhere in-between is a sweet spot that Senninger calls the ‘learning zone’, where there is enough discomfort to prompt inquiry and learning.

Applying these concepts to waterfall (Figure 1) versus agile (Figure 2) processes, it can be seen that waterfall processes are more likely to result in either “zero discomfort” or “too much discomfort”.

In the early stages of a waterfall process, the final outcomes are a long way off, allowing teams to sit in a comfort zone where “there may be little stimulus” for them to worry about exactly what they will deliver and when. However, as final deadlines approach, the comfort level is likely to skip the “sweet spot” in the middle and go straight to “too much discomfort” where teams are overwhelmed and highly stressed by the very real prospect of time and budget overruns and the delivery of a product that is substandard or doesn’t meet client requirements.

On the other hand, by breaking down an overall process into smaller iterative cycles, agile methods mean that teams are focused on reaching immediate and much more readily achievable goals or milestones. These smaller cycles create a more desirable level of discomfort – equivalent to the “sweet spot” of the learning zone in Figure 3 – that keeps teams engaged in the learning, collaboration, and task completion necessary for the achievement of the goals of the current cycle.

Header image: A daily Scrum team helps people control workload and schedule. Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

References:

- Nonaka, I., and Hirotaka, T., The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation, USA: Oxford University Press, 1995. ↩

- See https://www.scruminc.com/takeuchi-and-nonaka-roots-of-scrum/ (accessed 22 September 2019). ↩

- Senninger, T. (2000). Abenteuer Leiten – in Abenteuern lernen: Methodenset zur Planung und Leitung kooperativer Lerngemeinschaften für Training und Teamentwicklung in Schule, Jugendarbeit und Betrieb. Oekotopia Verlag: Aachen, Germany. ↩

- Senninger, T. (2000). Abenteuer Leiten – in Abenteuern lernen: Methodenset zur Planung und Leitung kooperativer Lerngemeinschaften für Training und Teamentwicklung in Schule, Jugendarbeit und Betrieb. Oekotopia Verlag: Aachen, Germany. ↩

Also published on Medium.