How do managerial heuristics emerge?

A newly published paper1 proposes a process model for the generation, articulation, sharing, and application of managerial heuristics, from their origin as unspoken insight, to proverbialization, to formal or informal sharing, and to their adoption as optional guidelines or policy.

Paper author Radu Atanasiu proposes the following definition of managerial heuristics:

Managerial heuristics are cognitive shortcuts for making decisions, that use fewer resources than analytical algorithms in order to reach good enough solutions for difficult managerial problems.

There are two main classes of heuristics:

Intentional heuristics – idiosyncratic heuristics that are learned from experience and employed consciously and purposefully

Unintentional heuristics – systemic, inherent or innate heuristics, that are used in a non-deliberate way.

As the purpose of the paper is to examine how managers and firms generate and apply their portfolios of heuristics, Atanasiu focuses on intentional heuristics.

Some examples of intentional managerial heuristics in different contexts are:

- internationalization – “choose location because skill sets are within reach”

- internationalization – “enter countries with lots of pharma activity and where rich pharma firms had headquarters”

- business strategy – “if 10% of customers say yes, then you have your target group”

- internationalization – “enter one country at a time”

- business strategy – “promote short offers in Facebook, long-term offers on the website”

- climbing on Everest – “if you see a damaged rope, you have to fix it right away”

- various – “hire enthusiastic and intelligent individuals over those with specific skills or experience.”

To infer how heuristics emerge, Atanasiu studies how proverbs emerge. Articulated heuristics are, like proverbs, short, catchy, generic decision rules. Like heuristics, proverbs are inductive in nature, born from experience, satisficing, and ecologically fit, being adapted to the context and environment out of which and for which they have been generated.

Sometimes, heuristics really are proverbs. One researcher gathered a collection of 186 heuristics used by entrepreneurs and a lot of these are, in fact, proverbs, for example “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket,” or play on existing proverbs, for example, “Timing is money.”

Like heuristics, proverbs are strategies for dealing with situations. Real-life management practice employs many such simple rules and most managers use a number of articulated, proverb-like heuristics. For example, “Sell in May and go away” as a guideline for investing.

Process model of how heuristics emerge

The process model for how heuristics emerge is shown in Figure 1, with each stage of the process then explained in the following sections.

Generation

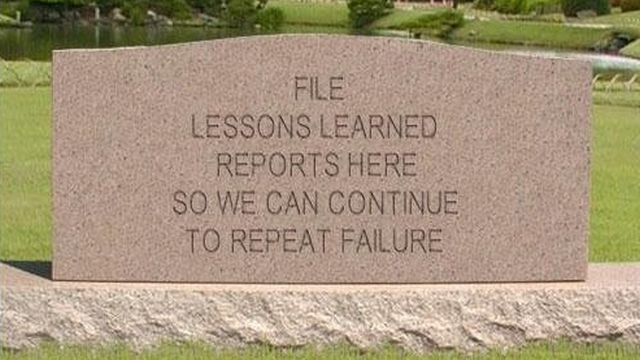

Heuristics are generated as lessons learned from negative outcomes. They are also cultivated by experience, with an interesting correlation found between the years of experience of managers and their inclination to create and use heuristics. Heuristics can be generated both by individuals and collectively, but when a heuristic is born in a group discussion, the first insight still originates from one individual.

Articulation

Articulation is defined as the process by which tacit knowledge is made more explicit or usable. The experienced manager first makes sense of how to prevent the negative outcome by creating a decision rule with (usually) one key criterion.

Heuristics subsequently go through a process of proverbialization. Proverbs are characterized by mnemonic robustness – they are articulated as to be easily remembered and passed forward. Tools such as parallelism, rhyme, alliteration, and the use of numbers are used to establish the mnemonic robustness. Although not all articulated heuristics have a proverb-like formulation, they are clearly expressed and can be easily remembered and communicated.

Some examples of the proverbial markers in heuristics are:

- “Sell in May and go away” – rhyme

- “Sell aspirins rather than vitamins” – rhyme, symmetry

- “It takes money to make money” – alliteration, rhyme

- “Companies to be acquired must have no more than 75 employees, 75% of whom are engineers” – repetition, use of numbers

- “A bad deal is better than a good lawsuit” – surprising contrast

- “Buy on the rumour, sell on the fact” – symmetry, parallelism

- “If there are 3 “ifs”, do not do it!” – shortness, use of numbers

- “Enter one country every two months” – shortness, use of numbers

- “If you pay peanuts, you get monkeys” – humorous twist

- “Every internal team should be small enough that it can be fed with two pizzas” – humorous twist, use of numbers.

Articulated heuristics then go through a constant refining process which renders them more precise and strategic, with a higher degree of abstraction and generality.

Sharing

Application

The dual sharing process can be paralleled with a dual process for adoption and application, with soft adoption turning shared heuristics into optional guidelines and hard adoption turning them into policies.

Soft adoption occurs through informal communication. Hard adoption of a heuristic as policy can be the consequence of hierarchical authority or of collective authority. For example, in the case of Jeff Bezos’ two-pizza rule (see above), his insight is shared and transformed into policy almost from inception, based on the hierarchical authority of the Amazon CEO.

Article source: The lifecycle of heuristics as managerial proverbs, CC BY 4.0.

Header image source: iStock.

Reference:

- Atanasiu, R. (2021). The lifecycle of heuristics as managerial proverbs. Management Decision. DOI 10.1108/MD-08-2019-1025 ↩

Also published on Medium.