Sensors are everywhere

As knowledge managers, should we limit the amount of information that sensors can collect?

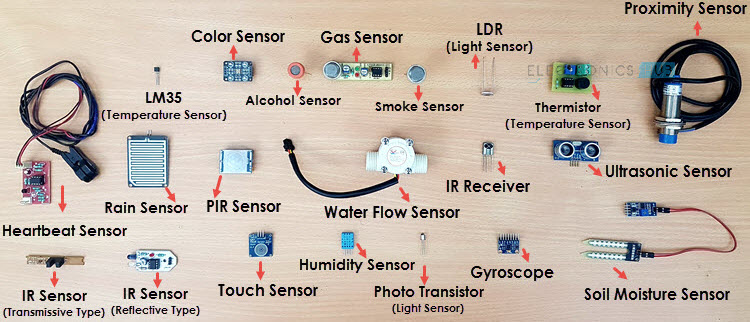

We must first understand and define what a sensor is:

- A device, which detects or measures a physical property and records, indicates, or otherwise responds to it1.

- A device, module, machine, or subsystem whose purpose is to detect events or changes in its environment and send the information to other electronics2.

- People being exposed to information that would be of significant value if collected, processed, and integrated into a common operating picture; hence, the concept of Every Soldier is a Sensor3.

- When the birds become silent during a walk in the woods, we listen for indicators of a predator nearby.

- When we are alerted by the sound of a rattle in areas with rattlesnakes, we immediately move away, as by reflex we know that this sound means there is the danger of a rattlesnake nearby.

When we think of sensors, we think of items such as these:

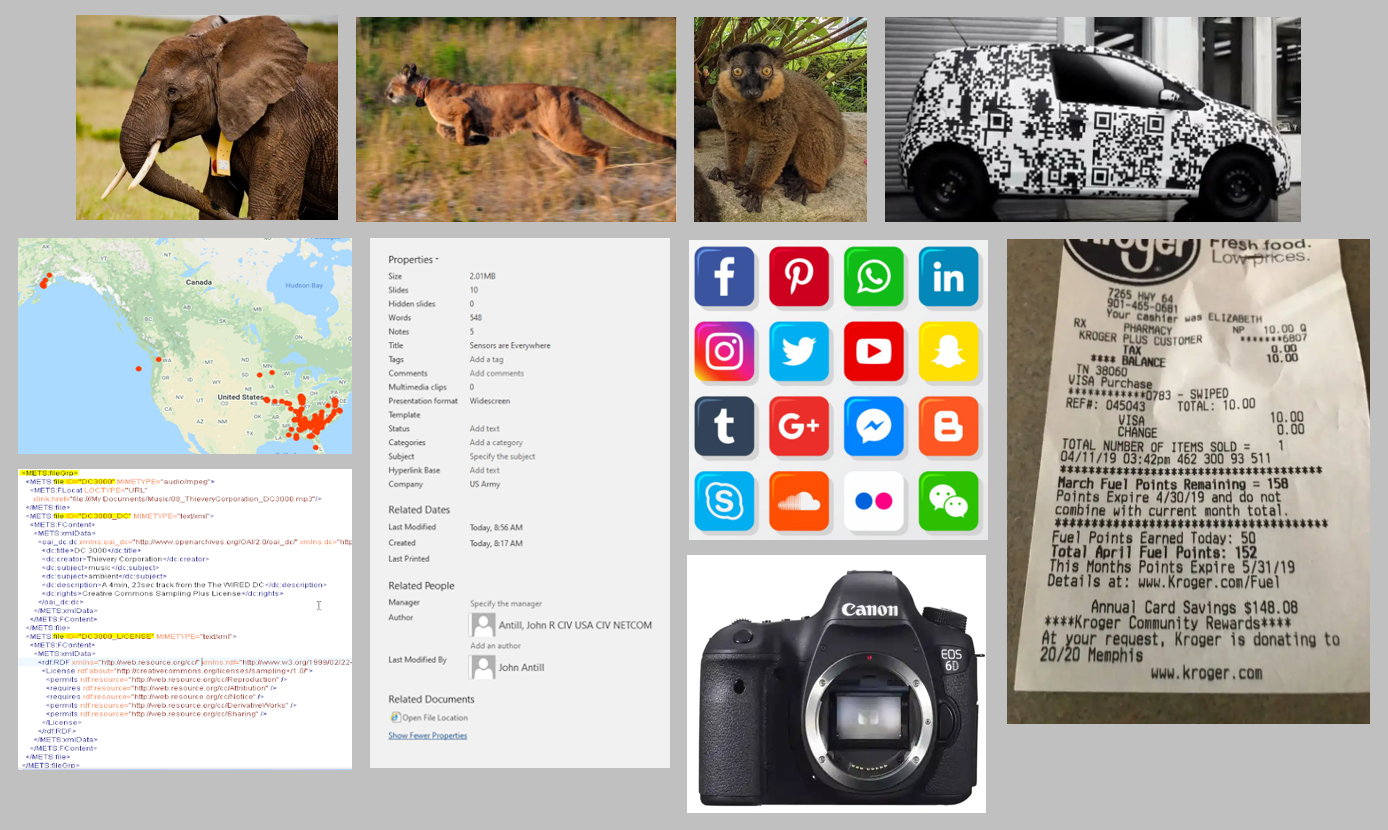

But these also all involve sensors:

So why is it important for us to understand that sensors are everywhere?

By understanding metadata we can see why the information is collected quickly. Metadata standards are intended to establish a common understanding of the meaning or semantics of the data, to ensure correct and proper use and interpretation of the data by its owners and users. Different types are technical, business, descriptive, and operational.

The cost of a sensor varies widely. In 2004, the average cost of sensors was $1.30, and by the year 2020, it was expected to come down to $0.384. With the decrease in the cost of sensors, now we can collect more data and can make decisions that are more intelligent at a lower cost.

On the other hand, for a tracking collar for animals5:

- $350 Standard VHF Collar

- $650 for Anti Snare Collar

- $3337.79 for GPS Collar

- $158 to 699 for a dog collar with GPS and health.

So why should we care about sensors?

We need to consider:

- What data are they collecting?

- What is the tagging process?

- Can we limit the sharing of the data?

- What are they showing?

- What happens if they are leaked?

We as humans have 5 basic senses, with a total of 15 to include all minor senses also. So we collect data, but most of it is ignored to only show us what is important. As we accelerate humans through technology and use, the number of sensors climbs quickly:

By understanding the use of sensors we can utilize them for good or nefarious purposes.

Good uses include:

- Conservationists using GPS to do things like monitor the movements of wild horses6 and figure out the migration habits of songbirds7 (with the help of miniature backpacks). The use of radio tagging even enables scientists to monitor migrating birds, bats, and turtles8 from the International Space Station.

- Loyalty programs or rewards programs, which are created by businesses to reward repeat customers. Using mobile apps, brands can develop ways9 for consumers to earn exclusive deals and discounts. A good loyalty program can improve user engagement, build brand recognition, and increase sales. Rewards members spend three times as much generating up to 70% of sales.

Bad examples include:

- Attempts – possibly by a poacher – to hack into GPS data showing the location of a Bengal tiger10, and wildlife photographers’ use of VHF receivers that pick up radio signals to figure out the locations of tagged animals11 in Banff National Park.

- The Target Store predicting customers’ pregnancies12, which has “creeped people out.”

Companies also buy and sell data all the time. These include datasets that forecast trends, analyze operations, marketing, sales, and other uses. There are even platforms establishing online stores to facilitate the easier buying and selling of data13.

Should we limit the amount of information that sensors can collect?

Now, we can see the implication of sensors. So in the end, should we limit the amount of information that sensors can collect? Yes, as knowledge managers, we must try to limit what we and our organisations need to use. This will help instill trust in our partnerships, as we control who has access to data, what is collected, and how it is collected. We must also offer a removal option to show we care about people’s data, and in this, recognize that cities, states, and countries have different standards for the use of data and removal.

The sensors we use to collect the data are as much our responsibility as what is in the databases that they inform.

Header image source: Gerd Altmann on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References:

- Oxford English Dictionary. ↩

- Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0. ↩

- AUSA. (2004, August). ES2: Every Soldier is a Sensor. Discussion Paper, Association of the United States Army (AUSA). ↩

- Honrubia, M. (n.d.). Industrial IoT is booming thanks to a drop in Sensor Prices. Ennomotive News. ↩

- Wildlife ACT. (2014, April 17). GPS and VHF Tracking Collars used for Wildlife Monitoring. Wildlife ACT Blog. ↩

- Nodjimbadem, K. (2016, November 22). How Conservationists Use GPS to Track the Wildest Horses in the World. Smithsonian Magazine. ↩

- Zhou, L. (2015, June 18). The Hottest New Accessory for Songbirds: Tiny GPS-Enabled Backpacks. Smithsonian Magazine. ↩

- Yong, E. (2016, July). The Space Station Is Becoming a Spy Satellite For Wildlife. The Atlantic. ↩

- Davis, B. (2021, December 25). The Average Cost of a Digital Loyalty Program in 2022. Stamp Me Loyalty Solutions. ↩

- Storm, D. (2013, October 16). Cyber-poaching: Hacking GPS collar data to track and kill endangered tigers. Computerworld. ↩

- Blakemore, E. (2017, March 2). Tracking Collars Can Lead Poachers Straight to Animals, Scientists Warn. Smithsonian Magazine. ↩

- Hill, K. (2012, February 16). How Target Figured Out A Teen Girl Was Pregnant Before Her Father Did. Forbes. ↩

- Liederman, E. (2021, July 26). Tech Platform Introduces Online Store for Buying and Selling Data. Adweek. ↩