An evaluation framework for extra-organizational communities of practice (CoPs)

Communities of Practice (CoPs) are an important knowledge management (KM) tool. They are a group of people who work together on an ongoing basis to share knowledge and expertise in regard to common issues, topics, or practices.

CoPs can be internal, which operate completely within an organization, or extra-organizational, which link people across different organizations and can also include people who may not be part of an organization.

In a recent University of Toronto PhD thesis1, Kaileah Alyssa McKellar proposes a template for the evaluation of extra-organizational CoPs. McKellar advises that the proposed framework can be a tool to support different stages of evaluation and multiple approaches to evaluation of extra-organizational CoPs, and can be helpful in both the planning and implementation phase of an evaluation.

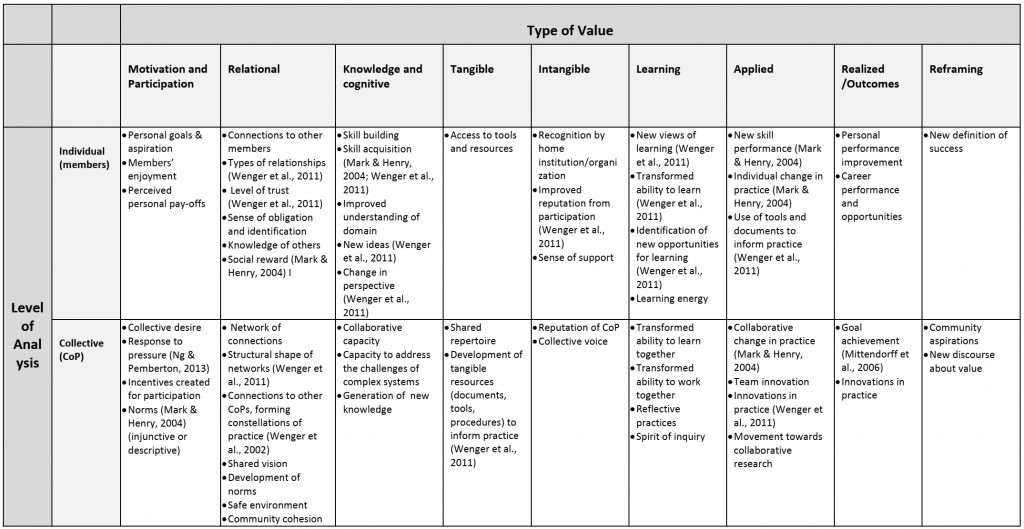

The McKellar extra-organizational CoP evaluation framework is shown in Figures 1 and 2, and descriptions of the ‘levels of analysis’ and ‘types of value’ follow the figures.

1. Levels of analysis

The ordering of the levels of analysis, starting at the top with individual, and then working towards larger or more distant groups, reflects the levels at which process and impacts can occur. While each level is represented by one row in the proposed evaluation framework, the framework can be adapted to represent the structure of particular CoPs. For example, one can adapt the framework to include multiple specific stakeholders or focus on core (centrally connected and engaged) and peripheral (loosely connected, infrequent participation) stakeholders at each level.

Individual

This represents the value for individual members (people) of the CoP. The base model includes one level to represent individuals within the CoP; however, depending on the characteristics of the CoP to which it is being applied (e.g., size, homogeneity of members), the evaluator could instead consider core and peripheral members or other types of individuals that are involved with the CoP. Given that there are different ways and degrees of participating, there could therefore be different types of members included in the framework. The individual level of analysis is most common in other CoP evaluation frameworks and is perhaps easiest to conceptualize.

Organization

While this framework provides guidance for extra-organizational CoPs, members’ organizations should be considered with respect to the value created by CoP processes. Despite extra-organizational CoPs not being housed within a single organization, and therefore less likely to receive organizational support, we can still expect to see value for most organizations to which CoP members belong (e.g., members bring back new skills to share with colleagues or other CoPs within the organization). Some organizations may also fund or support extra-organizational CoPs. The value to the organization, such as building their internal knowledge assets, may depend on intentional actions of the organization to leverage their access to CoPs.

Collective

Here we are looking at the collective value for the CoP as a whole or unit. There are both individual and collective manifestations in the motivations and processes of CoPs, therefore it follows that the outcomes of participation also occur at the individual and collective level. Early literature in CoPs promotes the collective as a unit of analysis and Wenger specifies that joint enterprise is considered a collective product.

External stakeholders

The level of external stakeholder is unique because it can represent individuals, organizations or target populations of the CoP. Stakeholders are actors (persons or organizations) with a vested interest; external stakeholders being those outside of the organization or CoP in this case. The distinction with this level of analysis is that they are external to the CoP, and the value gained is a result of the practices of the CoP. When determining which external stakeholders to consider in the evaluation, attention needs to be paid to the goals and strategy of the CoP, in particular, who or what group(s) is/are the CoP trying to influence, and what organizations are closely connected to the CoP. For example, evaluators might include the health care system as the focus for this level of analysis if relevant for the CoP. Robust techniques, such as stakeholder analysis, can be used to determine where external stakeholders attention should be focused.

Field

The field is related to the subject, issue or topic in which members share an interest or passion (i.e., related to the CoP’s domain). The field is comprised of both codified knowledge (i.e., formalized, written, archived), emergent knowledge, represented in the ongoing work of researchers and practitioners active in the field, and tacit knowledge, held by individuals; all of these elements both comprise the field and contribute to its evolution. The field is related to the concept of domain for a community of practice, where the latter (CoP) is subsumed within the former. A community of practice can also contribute to the development of a field.

2. Types of value

The types of value laid out in the framework draw heavily from Wenger et al.’s Value Creation Framework for promoting and assessing value created in communities and networks, with some modifications. We provide an overview of Wenger et al.’s types of value (value creation cycles), followed by a description of our modifications. The Value Creation Framework provides a way of categorizing generated value. This includes five types of value: immediate value, encompassing the idea that CoP activities and interactions have their own value, which is likened to satisfaction; potential value, which Wenger refers to as “knowledge capital” but which has included other forms of capital including social capital; applied value, representing changes in practice and leverage of potential value; and realized value, the outcomes of the practice change or applied value; and reframing value, defined as a “reconsideration of learning imperative and criteria by which success is defined”.

In the proposed framework, immediate value has been replaced with motivational and participation value, to capture both participation as well as reaction to the event. Immediate value was likened to satisfaction, but satisfaction can come from either the social rewards of participating in a CoP activity or from the collaborative learning that takes place. Immediate value was also defined as connecting with people, which overlaps aspects of the framework (relational value) . Motivation is a key driver of participation in communities of practice, therefore in this model it replaced immediate value. While types of value appear in separate columns, they are not entirely mutually exclusive. Moving from left to right generally reflects changes in the temporal nature of the value. The time-span of outcomes needs to be considered when conducting an evaluation. We turn to a description of each type of value. This evaluation framework uses the term value, not to align the framework with economic or management evaluation, but to select a more encompassing term. The term outcomes may also have been appropriate; however, value is considered to be a broader term encompassing different outputs, emergent states, underlying processes, intermediary outcomes, and long-term outcomes. Additionally, this term reflects the language of Wenger et al.’s Value Creation Framework, from which the types of value were adapted.

Motivation and participation value

This value refers to the motivational response of engaging with the CoP. It can include goals and aspirations, or positive feelings from participation. Motivation is an important intermediate outcome as it can drive further participation and development of practice. A “virtuous circle” involving motivation and participation has been used as a defining characteristic of CoPs (Thompson, 2005). Examples would be individual or collective goals and a motivated workforce, perceived personal pay-offs or norms at the collective level. At a member level, the source of motivation could be, for example, a strengthened social relationship, or a new skill developed by engaging in a CoP.

Relational value

Relational value includes both structural and relational aspects of social capital reflected in the number and quality of connections and the structure and knowledge of the community. Relational value can facilitate or limit other types of value; for example, trust plays a role in willingness of members of a network to share knowledge. Making connections and being able to identify subject matter experts can help speed knowledge transfer.

Knowledge and cognitive value

Knowledge and cognitive value includes knowledge and skill regarding the domain and practice. Knowledge is commonly conceptualized in two forms, tacit knowledge (‘know how’) and explicit knowledge (‘know that’). CoPs share both types of

knowledge and their advantage is often seen as facilitating tacit knowledge exchange. We see this as related to cognitive social capital (which focuses on the shared meaning and understanding that individuals or groups have with one another. This, in addition to the social capital captured in relational value, has been linked to team innovation.

Tangible value

Tangible assets are similar to the shared repertoire of the CoP. These can include documents, tools, procedures and methods. In some cases they will be similar to the output of the CoP. Value for the different levels includes access to researchers and their codified knowledge.

Intangible value

Intangible value is related to what Wenger et al. refer to as collective intangible assets. This includes a sense of support from the CoP, as well as reputational value. Examples include the status of an individual, the reputation of the CoP, its collective voice or the salience of the domain.

Learning value

Leaning value is more process-oriented than knowledge and cognitive value. It includes learning about how to work collaboratively and the development of strategies concerning the CoP. It includes reflective processes. This reflection facilitates an understanding of the state of the development from multiple perspectives; self-awareness can be leveraged to move forward. Learning is central to CoP theory and is connected to other factors important to CoPs, such as intrinsic motivation and skill development.

Applied value

This represents changes in practice and leveraging the capital that was created through the CoP. For example, the knowledge gained by CoP members can be applied within the CoP, so that the practice of the CoP changes, but it can also be applied in other settings with other partners. Applied value comes from the application of the above listed types of value. Examples include performing new skills, designing workshops differently, participating in collaborative research or leveraging the CoP’s collective voice. There are many contributing factors to whether practice in a CoP will change; for example, changing job behaviour may be prevented if the organizational climate is discouraging.

Realized value

Realized value can be thought of as the results of the CoP and, in particular, of applied value or behaviour change. While many of the types of value can be thought of as mechanisms or intermediate outcomes, realized value represents value that is more traditionally considered as outcome. The work of CoPs external to organizations often aims to influence external practices, be that changing policy, changing science or scholarship, or in the long-term, improving the health and well-being of communities. The outcomes will be highly dependent on the goals, domain, and practices of a CoP. Examples of realized value include performance improvement, or system change at the external stakeholder level.

Evaluators and CoP members might usefully customize the evaluation framework by separating this value into medium- and long-term outcomes. Medium-term outcomes would be those that could be expected within the lifecycle of the CoP, (e.g., 1-5 years); while long-term outcomes would be those that would be expected to occur beyond the lifecycle (e.g., 5-20 years). Note that as one moves from short- to long-term outcomes, there are more factors, aside from the CoP itself, that contribute to achieving outcomes. How the CoP and evaluator determine short- versus long-term outcomes will take into account the CoP’s stage of development.

Reframing value

Reframing value “is achieved when social learning causes a reconsideration of the learning imperatives and the criteria by which success is defined”. Like other types of value, this can happen at multiple levels. Achieving reframing value may mean breaking with existing structures and creating a new definition of success. Reframing value is related to both the concepts of “double-loop” and “triple-loop” learning; learning to learn is a contributor to transformation. Examples include new definitions of success at the individual or collective level or a change in relationship with external stakeholders. Reframing value can stem from strategic value and reflection as well as accepting and incorporating new practice.

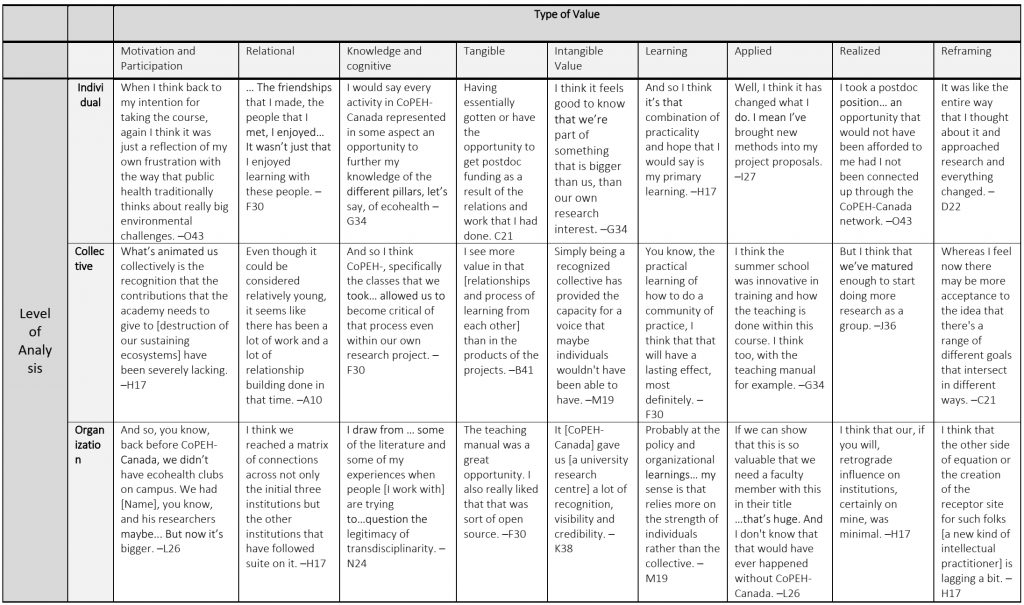

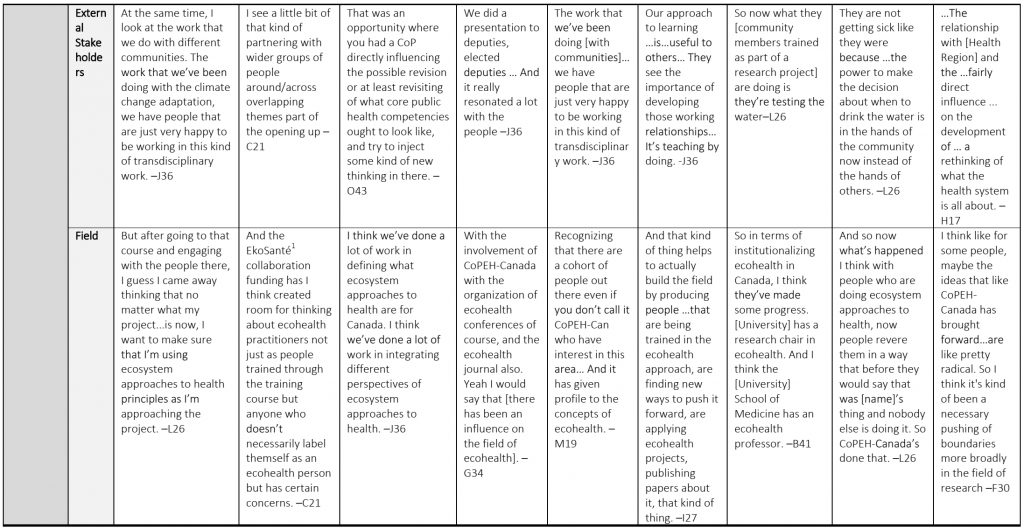

3. Example application

To assess the applicability of the evaluation framework for extra-organizational CoPs, qualitative interviews were conducted with an extra-organizational community of practice in Canada, the Communities of Practice in Ecosystem Approaches to Health (CoPEH).

Example quotes from the CoPEH interviews are shown in Figures 3 and 4. McKellar advises that these findings prove that the evaluation framework is comprehensive as a tool to understand the value generated, and is also useful in sharing results with members of the field.

Header image: A community of practice meeting. Dorine Ruter on Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

Reference:

- McKellar, K. (2019). Evaluating Extra-Organizational Communities of Practice (University of Toronto Doctoral dissertation). ↩

Also published on Medium.