What YOU can do about fake news

Fake news is nothing new, but became a significant issue in the context of the recent US presidential election. An analysis showed that fake election news outperformed real news on Facebook, and academics say that it’s likely that fake news influenced the election outcome. Disturbingly, a fake news story even led to a shooting inside a pizza restaurant. The story related to a conspiracy theory about Hillary Clinton running a child sex ring out of the restaurant.

Mainstream media outlets and social media platforms arguably have a responsibility to help prevent the spread of fake news. However, fake news would cease to be a problem if people stopped falling for it and circulating it, so there’s much that we as media consumers can also do. Here are some suggestions:

- Use the new Hoaxy tool

- Understand how social bots spread fake news

- Use the BotOrNot tool

- Develop and teach metaliteracy

- Keep the IFLA fake news guide handy

Use the new Hoaxy tool

In a recent article, I introduced “Hoaxy”, a platform that was being developed to track online misinformation. On 21 December, the Hoaxy beta tool was launched by the Observatory on Social Media (OSoMe) at Indiana University.

Users can now enter a claim into the Hoaxy website and see results showing both incidents of the claim in the media and attempts to fact-check it by independent organizations such as snopes.com, politifact.com and factcheck.org. A visualization can then be generated of how articles about the claim are shared across social media.

The visualizations illustrate both temporal trends, which plot the cumulative number of Twitter shares over time, and diffusion networks, which show how claims spread from person to person. Twitter is currently the only social network tracked, and only publicly posted tweets appear in the visualizations.

Importantly, Hoaxy doesn’t decide what’s true or false – it’s up to users to evaluate the evidence about a claim.

Understand how social bots spread fake news

You may not have realized that many social media accounts are in fact not human. Rather, they are social bots, with “bots” being short for software robots. Social bots are often benign, or even useful, for example chatbots can be a useful interface for customer support.

However, as discussed in a recent paper1, social bots are also being used with ill intent: “Social bots have been used to infiltrate political discourse, infiltrate the stock market, steal personal information, and spread misinformation.”

In a new article in The Conversation, academic Katina Michael reveals how social bots have been used to spread fake political news in a number of countries. For example:

Politicalbots.org reported that approximately 19 million bot accounts were tweeting in support of either Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton in the week before the US presidential election. Pro-Trump bots worked to sway public opinion by secretly taking over pro-Clinton hashtags like #ImWithHer and spreading fake news stories.

Use the BotOrNot tool

Before following an account on Twitter or retweeting its tweets, you can first check to see how likely it is that the account is a bot by using the BotOrNot tool2. Like Hoaxy, BotOrNot comes from the Observatory on Social Media (OSoMe) at Indiana University.

Users can enter a Twitter username into the BotOrNot website and it will give a score based on how likely the account is to be a bot. Higher scores are more bot-like. Use of this service requires authenticating with Twitter. Since its release in May 2014, BotOrNot has served over one million requests.

Develop and teach metaliteracy

Writing in The Conversation, academics Thomas P. Mackey and Trudi Jacobson argue that traditional literacy (reading and writing), information literacy (the ability to search for and retrieve information), and digital literacy (the ability to effectively use digital technologies) are not enough to equip people with the skills and knowledge to be able to identify and deal with fake news.

They recommend the development of metaliteracy, which emphasizes how we think about things: “Metaliterate individuals learn to reflect on how they process information based on their feelings or beliefs.” They do this by:

- Learning to question sources of information: Noting whether the information emanates from research or editorial commentary, distinguishing the value of formal and informal news sources, and evaluating comments left by others.

- Learning to observe their feelings when reading a news item: By reflecting on the way we are thinking about a news story, we will be more apt to challenge our assumptions, ask good questions about what we are reading and actively seek additional information.

- Understanding how information is packaged and delivered: A seemingly professional design may be a façade for a bias or misinformation.

- Knowing how to contribute responsibly: There are ethical considerations involved when sharing information, such as the information must be accurate. Individuals should also understand on a mental and emotional level the potential impact of participation.

When posting a tweet, blog, Facebook post or writing a response to others online, people need to think carefully about what they are saying.

In a recent article in The Verge, an information sciences professor talks about how school librarians can teach metaliteracy, and in a previous article I show how metaliteracy can be applied.

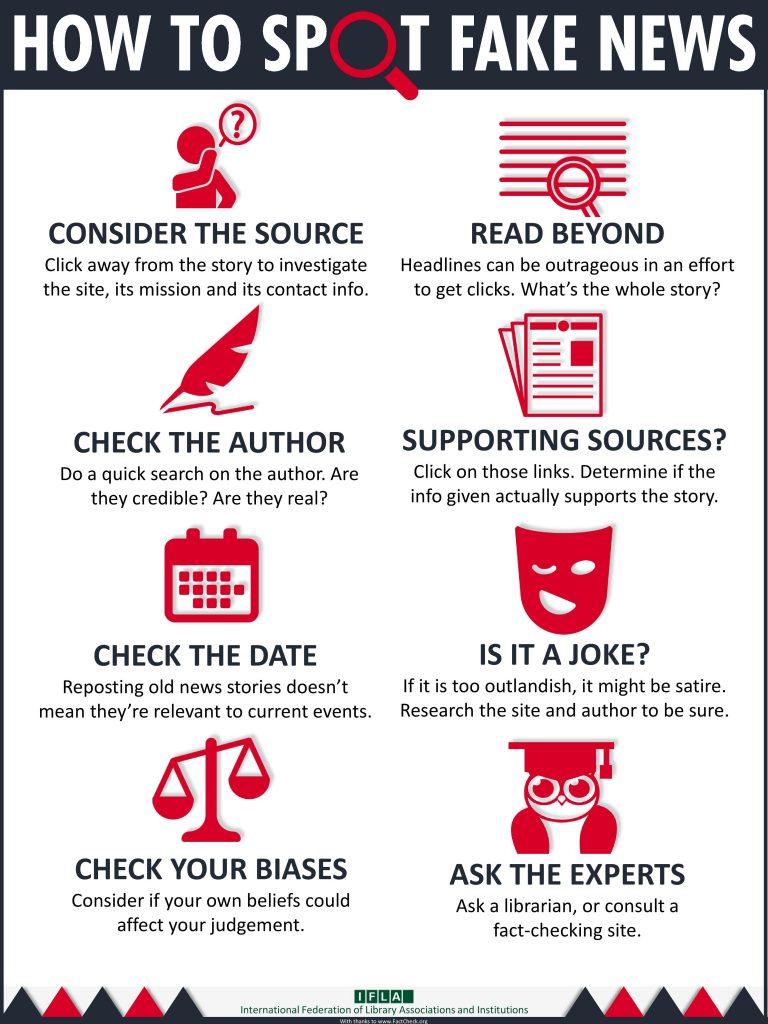

Keep the IFLA fake news guide handy

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) has made the infographic below to help you determine the verifiability of news items (the eight simple steps are based on the FactCheck.org 2016 article How to Spot Fake News).

Print it out and keep it handy, and share it with your family, friends, and colleagues.

References:

- Ferrara, E., Varol, O., Davis, C., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2016). The rise of social bots. Communications of the ACM, 59(7), 96-104. ↩

- Davis, C. A., Varol, O., Ferrara, E., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2016, April). BotOrNot: A system to evaluate social bots. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference Companion on World Wide Web (pp. 273-274). International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee. ↩

Also published on Medium.