Questioning the truth in the notion of “post-truth”

The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year for 2016 is “post-truth”, defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief”.

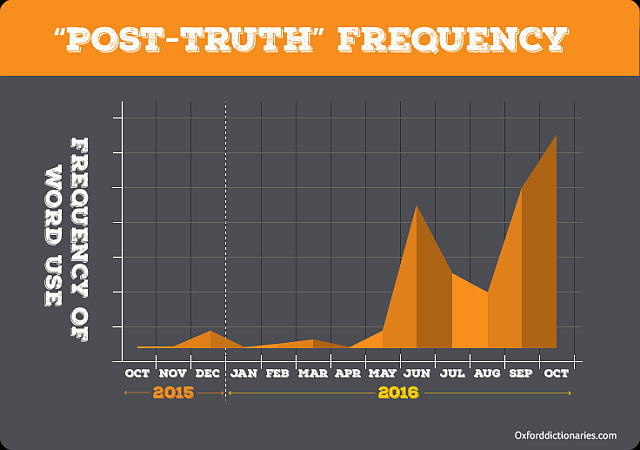

Post-truth was apparently first used with this meaning in a 1992 essay, and then later in the title of A 2004 book. But it wasn’t until the past year that this term came to be widely used and understood, as shown in the graph in Figure 1.

The spikes on the graph coincide with the 23 June 2016 Brexit referendum and the lead-up to the 8 November 2016 United States presidential election, where post-truth became associated with the phrase “post-truth politics”, which Wikipedia defines as “a political culture in which debate is framed largely by appeals to emotion disconnected from the details of policy, and by the repeated assertion of talking points to which factual rebuttals are ignored. Post-truth differs from traditional contesting and falsifying of truth by rendering it of “secondary” importance.”

Implicit in the emergence of the terms “post-truth” and “post-truth politics” is the view that the global information landscape has undergone a dramatic and sudden shift over the past year. Using these terms is to propose that only just a year ago, public opinion was based on objective facts, but is now based primarily on emotion and personal belief, and that political debate was based on evidence-based policy, but is now based primarily on emotional appeals in ignorance or rejection of the facts.

But is this really the case?

The flood of fake news that circulated during the United States presidential election campaign is seen as clear evidence of the arrival of a post-truth era. However, Robert Love, an adjunct professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, charts a very long history of fake news in a 2007 article in the Columbia Journalism Review:

Fake news has been with us for a long time. Documented cases predate the modern media, reaching as far into the past as a bogus eighth century edict said to be the pope-friendly words of the Roman emperor Constantine. There are plenty of reports of forgeries and trickeries in British newspapers in the eighteenth century. But the actual term “fake news”—two delicious little darts of malice (and a headline-ready sneer if ever there was one)—seems to have arisen in late nineteenth century America, when a rush of emerging technologies intersected with newsgathering practices during a boom time for newspapers.

Just as social media is doing now, the arrival of new technology—telegraph, trans-Atlantic and transcontinental cables, linotype, high-speed electric presses, halftone photo printing, telephone—revolutionised the media. By 1900, fake news was reaching disturbing proportions. The highly competitive nature of the big money newspaper industry was a big contributor to this:

By the century’s turn, the tallest buildings in New York and San Francisco were both owned by newspapers. And the business became so hypercompetitive that some reporters not only made things up but stole those fake scoops and “specials” from one another with impunity.

But what about post-truth politics?

Joanna Weiss writes in the Boston Globe that the nineteenth century was “a time [in US politics] when the party apparatuses were as ruthless as any super PAC [political action committee], the newspapers were proud to take sides, and outrageous charges went out in handbills, the precursor to TV ads and direct mail.”

She lists four campaigns that she considers “highlights of 19th-century bare-knuckle politics” over a period of more than 80 years: Jefferson v. Adams, 1800; Andrew Jackson v. John Quincy Adams, 1828; Abraham Lincoln v. Stephen Douglas, 1860; and Grover Cleveland vs. James G. Blaine, 1884.

Dick Polman, national political columnist at NewsWorks/WHYY in Philadelphia and a “Writer in Residence” at the University of Pennsylvania, describes Jefferson v. Adams as the Clinton v. Trump of its day:

Incumbent President John Adams and his surrogates slimed Jefferson as a God-hater who, if elected, would close the churches and import French revolutionaries to wreak violent havoc upon the land and foment “the insurrection of the Negroes in the southern states.”

Adams’ surrogates called Jefferson “an open infidel” who, if elected, “will be a center of contagion to the whole continent.”

One pro-Adams tract … warned the people of Delaware that “if Jefferson is elected, the morals which protect our lives from the knife of the assassin, which guard the chastity of our wives and daughters from seduction and violence, defend our property from plunder and devaluation, and shield our religion from contempt and profanation, will be trampled upon and exploded.” If Jefferson is elected, Americans would become “more ferocious than savages, more bloody than tigers, more impious than demons.”

And the top pro-Adams newspaper (the Fox News of its day) blared the slogan “JEFFERSON – AND NO GOD!!!”

Jefferson finally gave up trying to fact-check his accusers: “It has been so impossible to contradict all the lies that I have determined to contradict none; for while I should engage with one, they would publish 20 new ones.”

In return, Jefferson and his allies similarly slimed Adams.

The 1828 election battle between Andrew Jackson v. John Quincy Adams was more of the same: “by the time the votes were cast, both men would have wild stories circulated about their pasts, with lurid charges of murder, adultery, and procuring of women being plastered across the pages of partisan newspapers.”

While it included the rhetorically brilliant 1858 debates, the Abraham Lincoln v. Stephen Douglas 1860 election campaign honed in on the candidates’ physical appearances:

It’s hard to imagine political parties going there today: Lincoln supporters mocked Douglas, a stout man of 5’4″, for being “as tall as he is wide.” (Even Douglas’s allies call him “The Little Giant.”) Lincoln foes, well into his presidency, made fun of him for looking like an ape.

What did the public think about their appearances? Hard to know, especially given that the iconic circa 1860 portrait photograph of Abraham Lincoln is actually a fake, “having been created by splicing together the head of Lincoln with the body of Southern politician John Calhoun.”

The 1884 election battle of Grover Cleveland vs. James G. Blaine was just as bad:

During the 1880s, American politics witnessed the birth of its newest and most powerful player—journalistic sensationalism. And with it, presidential elections entered a whole new era of toxicity.

Its first victims were Grover Cleveland and James Blaine, who squared off during the 1884 election. The Blaine campaign was probably best known for its slogan “Ma, Ma, Where’s My Pa?” which played off accusations that Cleveland had an illicit affair that produced a child. Blaine’s Republican supporters latched onto the phrase quickly, chanting it in the streets as they rallied around their candidate. But the media latched onto it, too—this time with a newly invested interest in wringing out every drop of drama. In 1883, Joseph Pulitzer purchased New York World and upped the ante on selling stories. His emphasis on human-interest pieces and juicy scandals had newspapers flying off the racks, and other papers scurried to deliver the same. As long as people were buying them, nobody seemed to bother with the facts.

In these four nineteenth century election campaigns, “debate is framed largely by appeals to emotion disconnected from the details of policy, and by the repeated assertion of talking points to which factual rebuttals are ignored”—the Wikipedia definition of post-truth politics, which has supposedly only come into existence in the past year.

So, if we are really in a “post-truth” era, then it began a long time ago, and not just in the nineteenth century—for example in the 1690’s, only 100 years before Jefferson v. Adams election of 1800, the Salem witch trials were conducted in the United States. Not exactly evidence-based policy…

Also published on Medium.