Medical groupthink: is that surgery, procedure or medication really necessary?

All aboard the medical procedure “train”

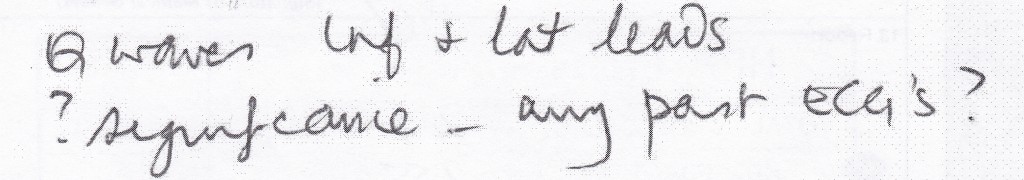

In 2011, an experience of chest pain led to an electrocardiogram (ECG) that showed abnormal Q waves. This can be a sign of a previous myocardial infarction (heart attack), so the cardiologist referred me for a coronary angiogram. The inference was that I may have suffered a recent ‘silent’ heart attack due to arteriosclerosis.

This situation left me feeling considerable disquiet. Firstly, it seemed strange to me that I could have suffered a heart attack without knowing it. Secondly, I had previous experience of medical professionals insisting I had no option other than surgery for another medical condition, when in fact another much better alternative was available. Thirdly, after reading about coronary angiograms I had significant reservations about the infection risk from this procedure.

I remembered that I still had my medical records from my time as an avionics technician in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). Looking through these records, I came across two ECG reports, one conducted in 1983, when I was 20 years old, and the other in 1988. Surprise, surprise both showed the same abnormal Q waves that had been observed in the 2011 ECG. The 1983 ECG includes the following comments:

So the assumption that I may have suffered a recent ‘silent’ heart attack due to arteriosclerosis was without basis. However, the cardiologist who had referred me for the coronary angiogram had not taken the time to consider alternative scenarios. My situation appeared very much like the one described by Dr. Eric Topol, an interventional cardiologist, in a New York Times article that I read at the time:

Dr. Topol said a patient typically goes to a cardiologist with a vague complaint like indigestion or shortness of breath, or because a scan of the heart indicated calcium deposits – a sign of atherosclerosis, or buildup of plaque. The cardiologist puts the patient in the cardiac catheterization room, examining the arteries with an angiogram. Since most people who are middle-aged and older have atherosclerosis, the angiogram will more often than not show a narrowing. Inevitably, the patient gets a stent.

”It’s this train where you can’t get off at any station along the way,” Dr. Topol said. ”Once you get on the train, you’re getting the stents. Once you get in the cath lab, it’s pretty likely that something will get done.”

A factor that had contributed to my questioning of the angiogram referral was my previous experience of incorrectly being told that I had no other option than surgery for another medical condition.

In 2004, I had been referred for surgery for large areas of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on my right temple. Because of the location and size of the BCCs, the surgery needed to involve a skin graft and carried the risk of both scarring and surgical infection. But I was told there was no alternative. The risk of infection was of significant concern to me, having been hospitalised in 2002 due to a serious infection from a small cut on my elbow, and with hospital infections being a significant problem.

Purely by chance, I happened to read a magazine article at the time about Imiquimod, a topical cream that was being used to successfully treat BCC and some other conditions. I immediately made an appointment with a different dermatologist and insisted on being prescribed Imiquimod. I proceeded with Imiquimod treatment on my BCCs through 2005 and 2006. The treatment was fully successful, with the BCCs completely gone, and the only evidence of their previous presence being a slight difference in skin colour in the treated area.

I also had significant concerns about the surgical infection risk from the proposed coronary angiogram as it is an invasive procedure. As with the BCC treatment, I was told there was no other option. However, my research revealed that this was not true. A non-invasive option was the cardiac CT scan. Although the earlier inference of a recent ‘silent’ heart attack due to arteriosclerosis could not have been true, I decided to have a cardiac CT scan given the long-term presence of abnormal Q waves. The cardiac CT scan revealed minimal arterial plaque in some areas and no heart problems. The chest pain that I had initially experienced was also further investigated and revealed to be muscular.

Questionable surgery and treatments

Given my experiences, it has been no surprise to read the Grattan Institute’s recent report Questionable care: avoiding ineffective treatment and an extract from Ian Harris’ new book Surgery, The Ultimate Placebo. Both highlight the widespread conduct of unnecessary surgery and procedures.

In a summary of the Grattan Institute report in The Conversation, the report authors state that:

For decades, clinicians and researchers have been concerned about patients getting treatments, including operations, that don’t work. As well as failing to treat the original health problem, ineffective care exposes patients to complications and side-effects and waste precious health-care resources.

Ian Harris is Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at the South West Sydney Clinical School of the University of New South Wales and the Director of Orthopaedic Surgery at Liverpool Hospital. In the extract of his new book, he highlights the groupthink of surgeons:

Without good scientific evidence, surgeons perceive the procedures they recommend to be effective – otherwise their colleagues wouldn’t be doing them, right?

Put simply, a lack of evidence allows surgeons to do procedures that have always been done, those that their mentors taught them to do, to do what they think works, and to simply do what everyone else is doing.

What should be done?

The Grattan Institute report recommends that better information needs to be provided to medical professionals, including guidance about which procedures should be avoided. Hospitals then need to be monitored in regard to implementation of this guidance. New recommendations in regard to tests, treatments and procedures from NPS MedicineWise, as summarised in ABC News, appear to go some way towards providing this guidance.

Patients also need to feel comfortable questioning the advice they are being given, so that they can ensure that all relevant information is being considered and that the pros and cons of all possible options are being explored. The recommendations from NPS MedicineWise include five questions that people should ask their doctor or healthcare provider:

- Do I really need this test or procedure? Tests may help you and your doctor or other healthcare provider determine the problem. Procedures may help to treat it.

- What are the risks? Will there be side effects? What are the chances of getting results that aren’t accurate? Could that lead to more testing or another procedure?

- Are there simpler, safer options? Sometimes all you need to do is make lifestyle changes, such as eating healthier foods or exercising more.

- What happens if I don’t do anything? Ask if your condition might get worse — or better — if you don’t have the test or procedure right away.

- What are the costs? Costs can be financial, emotional or a cost of your time. Where there is a cost to the community, is the cost reasonable or is there a cheaper alternative?

Image source: CPMC Surgery by Artur Bergman is licenced by CC BY-SA 2.0.

Also published on Medium.