Three types of knowledge

By Tobias Buser and Flurina Schneider. Originally published on the Integration and Implementation Insights blog.

When addressing societal challenges, how can researchers orient their thinking to produce not only knowledge on problems, but also knowledge that helps to overcome those problems?

The concept of ‘three types of knowledge’ is helpful for structuring project goals, formulating research questions and developing action plans. The concept first appeared in the 1990s and has developed into a core underpinning of transdisciplinary research.

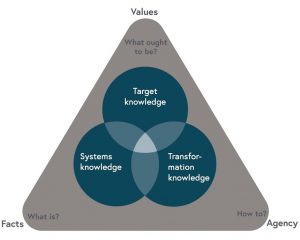

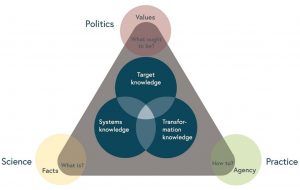

The three types of knowledge, illustrated in the first figure below, are:

- Systems knowledge, which is usually defined as knowledge about the current system or problem situation. It is mainly analytical and descriptive. For example, if you think of water scarcity, systems knowledge refers to producing a holistic understanding of the relevant socio-ecological system, including aspects like water availability, water uses, water management, justice questions, and their interrelations.

- Target knowledge, which is knowledge about the desired future and the values that indicate which direction to take. It relies on deliberation by different societal actors, and is based on values and norms. In the water scarcity example, ways of producing target knowledge could include participatory vision and scenario development with a wide range of stakeholders.

- Transformation knowledge, which is about how to move from the current to the desired situation. It includes concrete strategies and steps to take. In the water scarcity example, producing transformation knowledge could, for instance, employ a collaboration platform between water rich and water poor communes to coordinate just water distribution, as well as to provide detailed and feasible water saving measures.

The three knowledge types are equally important for societal change and they are interdependent. A specific project might focus on only one or two types, however it is important to keep them all in mind, as the missing knowledge may have been generated in another project.

Two particular traps to watch out for are:

- ignoring target knowledge production can mean that an implicit assumption of a desirable goal can be completely at odds with what different stakeholders aim for

- generating more and more systems knowledge, with no plan for using it to effect change.

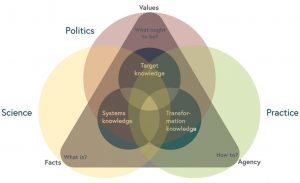

Relationship with facts, values and agency

The three types of knowledge can be usefully conceptualised as being located within a triangle delimited by facts, values, and agency, as shown in the figure immediately below. Facts are strongly associated with systems knowledge, values with target knowledge, and agency – the capacity to act in a purposeful way – with transformation knowledge.

Three questions are helpful for operationalizing this relationship:

- systems knowledge answers the question, ‘what is?’

- target knowledge addresses the question, ‘what ought to be?’

- transformation knowledge defines ‘how to?’

It is important to note that answers to each of the questions involve facts, values and agency to a certain extent. For example, the knowledge about ‘how to’ would be of limited use, or even dangerous, if not oriented towards desirable target values and based on sound facts.

Three spheres of influence: science, politics, and practice

The corners of the triangle can also be linked to spheres of influence, where different societal actors tend to have higher legitimacy, as shown in the next figure:

- facts belong to the sphere of science, with scientists as the most credible actors

- values and norms are generally in the sphere of political actors, depending on public debate and governments for their legitimacy

- agency is linked to the sphere of practice, with legitimacy resting with practitioners who know how things are done.

The three spheres, with their respective legitimised actors and attributes, provide one rationale for the importance of working with stakeholders from all three spheres when generating knowledge for societal change.

This third image (above) is too simplistic, as the knowledge types overlap and are interdependent. Furthermore, the spheres of influence of the different societal actors are also not independent. For example, actors from the political and practical spheres are also important holders of systems knowledge. Some scientists, for example, ethicists, explicitly work on values, while others, for example engineers, work on transformation knowledge. Finally, every research question is already a normative decision on what topic to focus on. In this regard, transdisciplinarity can be seen as working within, and creating spaces at the intersection of, all three spheres.

How does the concept of three types of knowledge and their relationships resonate with you? Do they reveal new things about your projects? What other concepts do you use to structure different types of knowledge and their links to project goals, research questions and action plans?

To find out more

These are some of the core ideas from the Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) “Partnering for Change – Link Research to Societal Challenges” which will be run for a second time starting on February 22, 2021.

The MOOC video about the concepts presented here can be seen on the Integration and Implementation Sciences (i2S) YouTube channel and on the MOOC website [and also available at the top of this page].

An exercise on the three types of knowledge tool is also described, with references, in the td-net toolbox.

Biographies

|

Tobias Buser is executive secretary of the Global Alliance for Inter- and Trans- disciplinarity (ITD Alliance) and project head of international networks and capacity building at the Network for Transdisciplinary Research (td-net), which is at the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences in Bern, Switzerland. He is a specialist for collaborative research processes, with experience in a) designing, conducting and reflecting stakeholder engagement processes, b) capacity building for transdisciplinary research, and c) conducting research on transdisciplinary research programmes, projects and stakeholder perspectives. |

|

Flurina Schneider PhD is an integrative geographer and head of the Land Resources Cluster at the Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern, Switzerland. Her research focuses on sustainability, justice, and human well-being in relation to land and water resources. She is particularly interested in how science, knowledge co-production and participation can contribute to sustainability transformations. |

Article source: Three types of knowledge, republished by permission.