Critical Eye: ISE4GEMs – A new approach for the SDG era

Critical Eye is a semi-regular feature where RealKM analyses and discusses the methodology and science behind claims made in publications. This article is also part of an ongoing series of articles on KM in international development.

UN Women recently released ISE4GEMs, one of a series of evaluation guidance documents that provide guidance on how to address the complexity involved in international development and shaping global agendas. It is reflective of the ongoing transformation of UN practices to incorporate systems thinking into its approach for achieving its 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. The introductory pages explain this focus explicitly:

[Members of the United Nations] need to think across and beyond one area of expertise or mandate and to understand how our actions contribute to the overall United Nations objectives. We need to analyse the environment as a set of complex, live ecosystems and to understand underlying organizing principles as well as the linkages, interactions, dependencies and power distribution among components and constituencies. And we must strategically identify leverage points in these systems to achieve maximum

impact. United Nations leaders must therefore shift from linear thinking to non-linear, systems thinking.

— UN Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB/2017/1)

The authors of the guide state their reasoning for adopting systems thinking up front:

A new paradigm is emerging that starts with the premise that each intervention is an opportunity for learning how to influence desired social change … [moving] away from the idea of conducting evaluations primarily for accountability against specific planned results, towards acceptance of the reality that “we do not know what we do not know” during any programme planning or implementation process …

But applying systems thinking to organizational analysis requires a profound shift in a basic tenant of evaluation: the unbiased observer (e.g., the evaluator). Traditionally, evaluator objectivity has been achieved by ensuring that one does not interact with the programme, organization or system to be evaluated—remaining “outside” of the system. Yet systems thinking reminds us that even from the outside of a system, evaluators cannot be entirely separate or objective. In defining what constitutes the system, and conducting analysis from their individual vantage point, evaluators engage with the system itself. Thus, systems theory teaches us that evaluation is never entirely objective or value free.

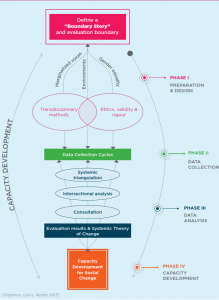

The ISE4GEMs framework involves identifying both a system to be evaluated and a system of the intervention that is being evaluated, with feedback loops “providing information about opinions or attitude, change and resistance, and actions taken”. Evaluation is guided by the use of systemic triangulation, a method that seeks to identify and reconcile three components:

- FACTS: Findings and evidence of change

- VALUES: Perspectives on the meaning of change

- BOUNDARY ANALYSIS: Interpretation of change within a specific boundary

The framework systematically identifies how to work through each aspect of evaluation, including reviewing data collection and analysis methods, participatory data interpretation, and the establishment and testing of a systemic theory of change (SToC).

A SToC is developed including “strands or predictions” about both systems that will draw on one or multiple theoretical positions. A SToC will often explicitly describe the desires, wills, relationships, and power imbalances of participants in the system as a key driver of transformational change.

Acknowledging the imperfection of any such description of systems drivers, the authors go on to state, “While even the SToC has limitations in terms of addressing the complexity of contexts, the complexity must always be considered and stated explicitly up front”. The authors posit that a sound SToC “broaden[s] our understanding of desirable social change processes and the complexity around supporting them”.

A key part of the effectiveness of use of SToCs comes from performing interventions and evaluating the results. Narratives of the SToC may either reinforce (concurrent with) or contradict (contrast with) the evaluation evidence. Either way, the identification of emergent behaviour and feedback loops is sought for incorporation into an updated SToC model.

The guide provides a compelling model for systemic interventions, using the Cynefin domains as a high-level descriptor of types of systems behaviour. It’s well-written and easy to follow, with lots of practical advice and process detail. However, the most striking aspect of the document for me is that how it highlights that doing KM interventions does not guarantee objectively “good” or “bad” outcomes. All evaluation of outcomes must happen within a moral and ethical framework – whether or not that framework is made explicit.

I have quite deliberately ignored the intersectional and feminist viewpoints promoted in this document, because it is clear that it would be just as easy to undertake the same practices from a conservative or reactionary viewpoint. It’s a timely reminder that knowledge management is a method, and not an ideology – a lesson that all KM practitioners would do well to bear in mind.