South Australian COVID-19 outbreak highlights how pandemics need a different disaster management approach

Last Wednesday, Australians tuning into the news were shocked to see Steven Marshall, the Premier of South Australia, making the sudden announcement of a major six-day COVID-19 lockdown for that state.

The lockdown began on Thursday, and is even more strict than the one implemented to control the second wave outbreak in the state of Victoria. All schools, hotels, cafes, takeaway food outlets, and the construction industry have been closed, and people are restricted from going outside their homes.

The South Australian Premier has stated that the strong lockdown measures are aimed at preventing a second wave. Like the outbreak that caused Victoria’s second wave, the South Australian outbreak has its origin in a hotel used for the 14-day quarantine of people returning to Australia from overseas.

Victoria’s second wave can be traced back to coronavirus transmission from returned travellers to staff, including security guards, at two quarantine hotels. The original outbreak is believed to have been caused through environmental transmission due to poor infection-control practices at one of the hotels.

South Australia’s outbreak can be traced back to a returned traveller transmitting the coronavirus to a cleaner at the Peppers Waymouth quarantine hotel via a contaminated surface. It is believed that the cleaner then infected two security guards. She is also the daughter of an 80-year-old who attended hospital and sparked the alert.

It was then believed that the coronavirus had been passed to a second quarantine hotel, the Stamford Hotel, through surface transmission at the Woodville Pizza Bar. A security guard at the Peppers Waymouth quarantine hotel also worked at the Woodville Pizza Bar, and a Stamford Hotel employee advised contact tracers that he had purchased a takeaway pizza from the Woodville Pizza Bar.

Lessons not learned?

There are significant similarities in the Victorian and South Australian outbreaks, with a person who worked as both a security guard at the Peppers Waymouth quarantine hotel and in the Woodville Pizza Bar having been a key vector in the South Australian outbreak. Given this, a medical expert has questioned whether South Australia has adequately considered the lessons from the Victorian outbreak. Professor Catherine Bennett, Chair in Epidemiology at Deakin University, has argued that workers in quarantine hotels need to be paid more so that they don’t work in other jobs and risk coronavirus infection.

We’ve previously featured Professor Bennett’s analysis of the problems with Victoria’s contact tracing. She discusses how contact tracers from Victoria had travelled to New South Wales (NSW) to learn from that state. In contrast to the situation in Victoria, NSW’s system of decentralised local area health districts meant when the second wave hit, that state was able to draw on teams embedded in their local communities to manage contact tracing.

However, South Australia’s Police Commissioner Grant Stevens strongly rejected Professor Bennett’s comments, stating that:

Your expectation is that people who work in a quarantine hotel will be isolated in a complete bubble from the rest of the community while they’re providing that service. That’s not just security guards. That’s police officers, it’s nurses, it’s caterers, its cleaners, its hotel staff, it’s the Australian Defence Force. Your expectation is unreasonable.

But in a dramatic twist on Friday, it was revealed that the Stamford Hotel employee who had advised contact tracers that he had contracted COVID-19 through purchasing a takeaway pizza from the Woodville Pizza Bar had lied. He was actually employed at the Woodville Pizza Bar! In response, South Australia’s Premier Steven Marshall has ended the lockdown early.

So, just as the coronavirus had been transmitted to the Woodville Pizza Bar by someone who was working in both a quarantine hotel and the pizza bar, it had also been potentially transmitted out of the Woodville Pizza Bar by someone working in both a quarantine hotel and the pizza bar. This further reinforces Professor Bennett’s perspective, and indeed, the Victorian COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry Interim Report and Recommendations1 which state that:

Accepting the need to bring in expertise, every effort must be made to ensure that all personnel working at the [quarantine] facility are not working across multiple quarantine sites and not working in other forms of employment.

… every effort should be made to have personnel working at quarantine facilities salaried employees with terms and conditions that address the possible need to self-isolate in the event of an infection or possible infection, or close contact exposure, together with all necessary supports, including the need to relocate if necessary and have a managed return to work.

In response to these recommendations, Victorian Premier Dan Andrews has stated that:

Everybody who works in this program will either work for the Victorian government or be exclusively contracted for this purpose and this purpose only.

We will advance contact trace every single person who works in this program to work out who they live with, what these people do for a living.

We don’t want a situation where someone is sharing a house with an aged care worker. We think that would be an unacceptable risk.

If Victoria can rapidly respond in this way then so can South Australia, and so can every other Australian state and territory. This is particularly important as pressure mounts for Australia to open up to more international arrivals, which can only be done successfully if hotel quarantine is managed in the safest possible way.

While the Victorian COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry Interim Report and Recommendations were only released on the 6th of November, processes through Australia’s National Cabinet should have enabled the government of South Australia to have been well aware of the inquiry recommendations the moment that the report was released, and also well aware of the planned response from the government of Victoria the moment that was announced. So rather than flatly rejecting the outcomes of Victoria’s inquiry, South Australia could and should have instead been actively learning lessons from Victoria and acting to rapidly implement hotel quarantine employment actions paralleling those announced by Dan Andrews.

In the wake of the pizza worker’s lie being exposed, South Australia’s Premier Steven Marshall has reacted angrily, saying that he was “fuming” in regard to the person’s actions, and that police would look at “all and every avenue to throw the book at this person.”

However, others have called out the Premier’s actions in making the pizza worker the scapegoat for systemic failures that are within the area of responsibility of his government. Ryan Batchelor, executive director of the McKell Institute in Victoria, has stated that:

It seemed like the authorities were saying: largely this is the fault of the person who lied to us. The danger here is that this is portrayed as the actions of one person when it actually points to some more systemic issues with the way we work.

The fact remains that this kind of thing could happen tomorrow, or next week, or in the future as long as we have workers who are engaged on contracts, as casuals, with no securities who are being put on the frontline of a global health pandemic.

This again strongly reinforces Professor Bennett’s perspective, the Victorian COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry Interim Report and Recommendations, and the response of Victorian Premier Dan Andrews to those recommendations. It again confirms that rather than flatly rejecting the recommendations of Victoria’s inquiry and engaging in emotive blame shifting, South Australia could and should have instead been actively learning lessons from Victoria and acting to rapidly implement hotel quarantine employment actions paralleling those announced by Dan Andrews.

But it’s not that simple

But that conclusion isn’t the end of the story. As we’ve previously discussed2 in RealKM Magazine, COVID-19 is a wickedly complex issue. So we need to explore why South Australia is reacting in this way.

Two news reports from the medical profession provide some solid clues. In May this year, newsGP, the news hub for the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), carried an article with the title “GPs at the forefront of South Australia’s successful efforts to tackle coronavirus.” The article states that:

The state has been among the nation’s leaders in controlling the virus – here’s how … Welcome to South Australia’s conquering of the coronavirus, with GPs very much at the forefront.

But then last week, as South Australia’s new outbreak was unfolding, the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) (South Australian Branch) published a news item stating that:

Victims of our own COVID success

South Australia’s success in curtailing the coronavirus may also have contributed to the latest alarming outbreak as people became more relaxed.

“The reality is that the system, both the community at large and the health system, has become somewhat a bit more relaxed because we weren’t seeing the virus with all the testing that was happening,’’ ANMF (SA Branch) CEO/Secretary Adj Associate Professor Elizabeth Dabars AM told ABC Radio’s David Bevan this morning.

These articles suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic in South Australia has been thought of as a one-off event, and that once it was successfully brought under control, it could then be considered as having been successfully “conquered.”

Similar thinking has also been evident in regard to Australia’s overall response. For example, an article published in April described Australia as being “a “rare example” among Western countries amid the coronavirus pandemic,” and another published in June labelled Australia’s response to the coronavirus as being a “triumph.” Soon after, Victoria’s second wave outbreak would expose the dangerous folly of such thinking.

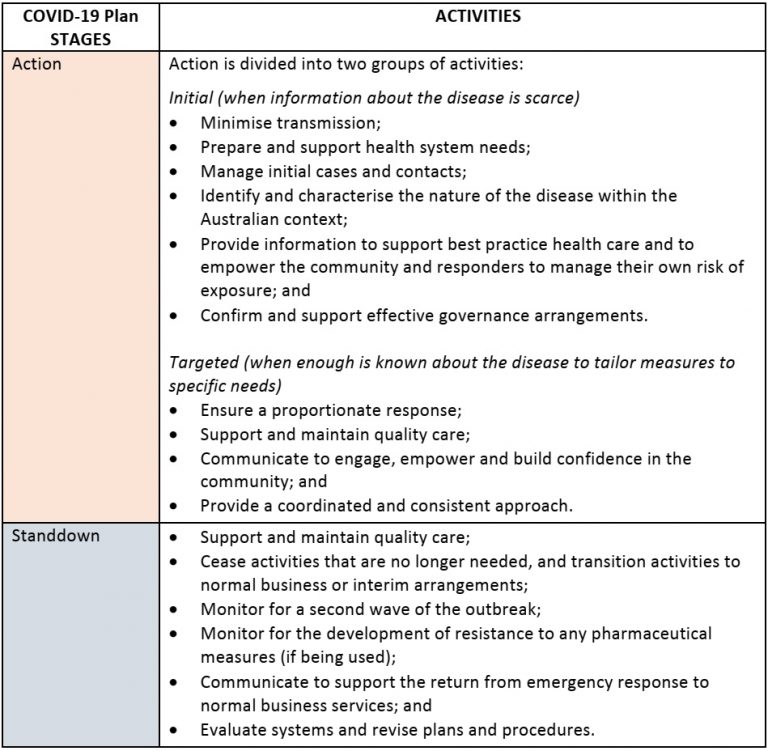

Indeed, the notion that the response to COVID-19 involves the simple and linear stages of “action” followed by “standdown” is actually the basis for the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)3, as shown in Figure 1. This plan is directly based on the Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI)4 which had been prepared prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A key difference is that while the AHMPPI has the three response stages of standby, action, and standdown, the COVID-19 Plan only has the two stages of action and standdown. This is because at the time of the publication of the COVID-19 Plan, Australia already had COVID-19 cases.

The approach in both the AHMPPI and COVID-19 Plan reflects the simple and linear “prevention, preparedness, response and recovery” approach to disaster management in Australia. The Australian Emergency Management Arrangements Handbook5 states that:

The Australian approach to managing emergencies recognises four phases of emergency management: prevention, preparedness, response and recovery. This is abbreviated to PPRR.

Some jurisdictions are redefining PPRR to three phases of the ‘before’, ‘during’ and ‘after’ the emergency. Both approaches are in use in Australian states and territories.

Pandemics are not like other disasters

However, a recently published paper6 makes the important point that pandemics are not like other disasters.

Pandemics have a number of key characteristics that are distinct from those of other natural disasters such as earthquakes, bushfires, and floods. These include:

- pandemics have a wave pattern behaviour, and might re-infect the same affected area or population

- disease outbreaks can cross geographic boundaries to become a global phenomenon, and have mutative and adaptive behaviours

- pandemics are population discriminative (that is, there are particular classes of people that are more vulnerable than others)

- spread patterns are influenced by different factors including pathogen contagion, demography, and behaviour, creating hotspots that “move” uncontrolled to other locations depending on population movement

- disease outbreaks have a deterministic and high effect on the health workforce itself (thus reducing the capacity of health systems to react).

One basic, crucial difference between pandemics and other natural disasters is that pandemics are not single, discrete, and time-bounded events. Pandemics are instead a continuous process that operates over a time horizon which lasts until there is extinction of the pathogen or the introduction of a vaccine. Another crucial difference is that while other disasters are bounded in spread and damage, typically being very localised, pandemics can spread globally.

These key differences mean that standard approaches to disaster management are less relevant to pandemics. Disaster management aims to reduce or avoid the potential losses from hazards, assure prompt and appropriate assistance to victims of disaster, and achieve rapid and effective recovery. Pre-disaster reduction is performed by risk and vulnerability assessment, risk reduction, and disaster preparedness. Post-disaster recovery is performed through relief, early recovery transition, and reconstruction.

However, pandemics have a slow and progressive explosion, which overlaps and interacts with relief and recovery. While there is an urgency of managing early recovery, a similar (if not higher) urgency needs to be devoted to risk reduction and the preparedness of other populations. Disaster management phases and targets overlap.

On this basis, serious shortcomings are immediately evident in the response plan shown in Figure 1 above. Standdown cannot occur until there is extinction of the pathogen or the introduction of a vaccine, so monitoring for and responding to a second wave (and subsequent waves) must be part of the action stage and not the standdown stage. Just as Victoria did earlier in the year, with devastating consequences, South Australia had moved into the standdown stage when it should have still been in the action stage.

Because pandemics have a slow and progressive explosion, which overlaps and interacts with relief and recovery, rapid loop learning in the face of uncertainty needs to be an essential activity in the action phase. An example of this learning approach is the Nightingale learning system7.

It appears that Victoria may now have come to this realisation, but not yet South Australia. But South Australia can’t be expected to change its approach while the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) continues to describe an approach that doesn’t reflect the key differences between pandemics and other natural disasters.

The Australian Government can’t have been expected to have adequately comprehended these differences in advance either, with the world not having experienced a global pandemic for more than 100 years and the world being a very different place now to what it was then. However, now that the differences are known, the Australian Government has a responsibility to also apply rapid loop learning and immediately act to update both the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI).

Header image source: Hans Braxmeier on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References:

- Coate, J. (2020). COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry Interim Report and Recommendations (6 November 2020). Parliamentary paper no. 169 (2018-2020). ↩

- Sahin, O., Salim, H., Suprun, E., Richards, R., MacAskill, S., Heilgeist, S., … & Beal, C. D. (2020). Developing a Preliminary Causal Loop Diagram for Understanding the Wicked Complexity of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Systems, 8(2), 20. ↩

- Australian Government Department of Health (2020). Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). February 2020. ↩

- Australian Government Department of Health (2019). Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza (AHMPPI). August 2019. ↩

- AIDR (2019). The Australian Emergency Management Arrangements Handbook. Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience (AIDR) and Australian Government Department of Home Affairs. ↩

- Ammirato, S., Linzalone, R., & Felicetti, A. M. (2020). Knowledge management in pandemics. A critical literature review. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1-12. ↩

- Bohmer, R., Shand, J., Allwood, D., Wragg, A., & Mountford, J. (2020). Learning systems: managing uncertainty in the new normal of Covid-19. NEJM Catalyst, 1(4). ↩

Also published on Medium.