A model for rapid learning and action in the face of COVID-19 uncertainty

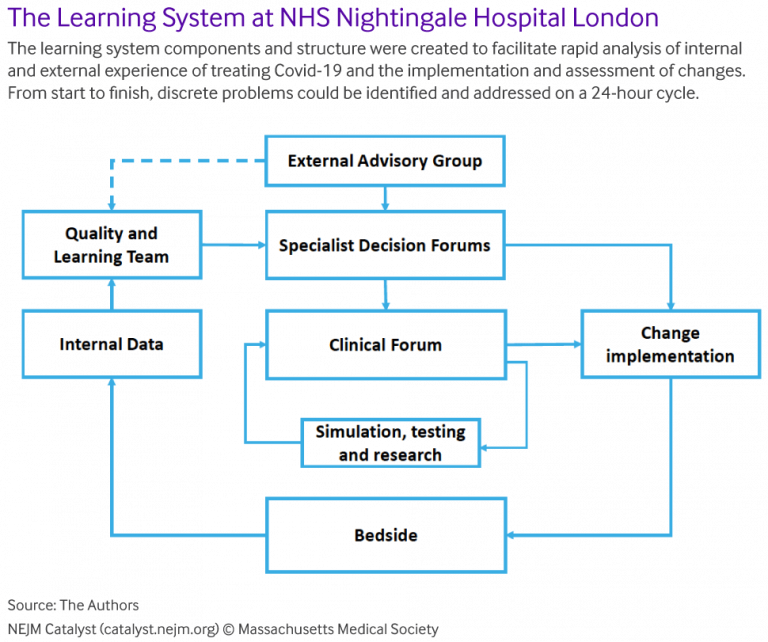

The uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic has meant that health care organisations have needed to learn quickly and act as fast as possible. To quickly create and refine a care delivery system for COVID-19 ICU patients, the NHS Nightingale Hospital London has implemented a “learning system” model. The aim of the learning system is to bring the best knowledge to every bedside, and improve the patient and staff experience day by day.

Nightingale Hospital is a temporary expanded capacity facility set up in the ExCel convention and exhibition centre in London. It operated during the first wave of COVID-19 in the United Kingdom, and has since been placed on standby.

The Nightingale learning system involves identifying and addressing problems on a 24-hour cycle, and is described in a recent paper1 in the journal NEJM Catalyst.

The learning system was found to enable a high level of reporting of problems and incidents. The incident rate fell steadily over time, potentially due to the proactive approach to problem solving and learning. In exit interviews, staff reported feeling encouraged to challenge, learn, and change, which enabled them to achieve a rapid turnaround of ideas and actions.

Transferability of the learning system

The paper authors consider that what is likely most transferable from the Nightingale example is the learning system’s architecture, not the specific implementation tactics. They state that the architecture is applicable to any health care delivery organisation, and is also relevant to both the challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and of managing care systems in normal conditions.

The authors alert that “A learning system only functions and supports the necessary learning culture when it is a system not simply an unconnected set of components.”

I suggest that the architecture also has potential application beyond health care, particularly in other settings where rapid cycles of learning and action are desirable, for example as I’ve previously discussed in regard to Boeing, Takata, and Toyota.

Architecture of the learning system

The structural and process components of the Nightingale learning system are shown above, and were designed to do five things:

- Create a rich data stream

- Analyze and test insights

- Make redesign decisions

- Rapidly implement planned changes

- Close the loop by checking reliability and effectiveness.

Data collection

A small Quality and Learning team with expertise in innovation, improvement and governance received inputs from multiple data sources:

- Incidents

- Bedside Learning Coordinator

- Staff survey

- Staff suggestions

- Clinical forum

- Hospital performance dashboard

- External evidence

- Clinical audit

- Mortality reviews

- Complaints.

The paper authors advise that there was a desire to capture not only quantitative data, but also qualitative data from staff: their insights into better ways of delivering care under difficult circumstances, personal reports of their own physical and psychological wellbeing, and their observations of patterns in the novel disease. Because research suggests that staff will typically keep such insights to themselves, the new role of Bedside Learning Coordinator was created.

The Bedside Learning Coordinators engaged with staff as they went about their work, asking questions about what was going well or badly. They used a structured data collection form to record perspectives, ideas, safety concerns, and observations, and occasionally provided assistance.

Analysis

Data were collated and evaluated by the Quality and Learning team, and then responses to the identified problems were triaged into three categories:

- Fix – Resolve problems in reliably doing what had been committed to be done. These were usually issues that could be resolved with rapid operational changes.

- Improve – Find better ways of delivering standard care; improve what is currently being done.

- Change – Significant changes in clinical or operational practice.

Decision-making

A daily Clinical Forum encouraged learning and change by making leadership accessible and facilitating rapid collaborative decision-making. It focused on areas for cross-team collaboration and was the setting in which changes and improvements were recommended, discussed, and actioned. To support a learning culture, anyone was permitted to raise a new issue at the Clinical Forum.

Most improvements and changes were agreed immediately, but some issues were assigned a task and finish group, or returned to the originating sub-group or recommending staff group for further evaluation.

Implementation into action at the bedside

The paper authors alert that health care is notorious for its slow pace and unreliability of innovation adoption, and a key challenge in any learning system is getting change into practice as soon as possible. To address this, the Nightingale learning system included by design multiple channels for communicating and implementing change.

Closure: checking reliability and effectiveness

The authors further alert that a common complaint from staff who are asked to participate in change programs is that although they provide many suggestions for improvements, they don’t see changes happening as a result. To address this, as a final step to close the loop, staff using the suggestions mobile phone app were sent messages when their suggestions had been actioned, and “we said, we did” boards were placed at the entrance to the ward and were updated regularly.

The Bedside Learning Coordinators also undertook ad hoc audits to confirm that changes had been successfully implemented and were having their desired impact, and these audit results were presented back to the daily Clinical Forum.

Header image: The military and contractors build the Nightingale Hospital for COVID-19 patients at the ExCel convention and exhibition centre in London. Source: Number 10 on Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Reference:

- Bohmer, R., Shand, J., Allwood, D., Wragg, A., & Mountford, J. (2020). Learning systems: managing uncertainty in the new normal of Covid-19. NEJM Catalyst, 1(4). ↩

Also published on Medium.