Are you an unwitting mercenary in the dirty Facebook disinformation wars?

We’re horrified to think that there are people who sign up to become mercenaries in wars against our own governments. But that is effectively what some people are allowing to happen to them on Facebook.

These wars are being fought with disinformation rather than guns and missiles, but innocent people are still being hurt. The uncomfortable truth is that those who share this disinformation are holding the internet equivalent of a smoking gun.

The evidence of real warfare is abundantly clear

When the word “warfare” is used it brings to mind thoughts of military battlefield conflict, so the idea that using disinformation to interfere in the political system of another country constitutes warfare may at first seem incongruous. However, this type of psychological manipulation has long been seen as an aspect of information warfare.

For example, Martin C. Libicki Writes in a 1995 United States National Defense University paper1 that “Arguable forms of warfare include psychological operations against the national will and culture.”

Libicki’s paper predates social media and YouTube, so he could never have anticipated that these platforms would become weapons of information warfare. But it’s abundantly clear now. As RealKM’s Stephen Bounds states in a 2017 survey that sought expert opinion on the future of truth and misinformation online, “This is the new reality of warfare today. Wars are going to be literally fought over ‘information supply lines,’ much as food supply lines were critical in wars of years gone by.”

The body of evidence documenting these disinformation wars continues to grow. The Computational Propaganda Project at the University of Oxford has been investigating the global disinformation order since 2012. Its latest report2, titled The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation, includes the finding that:

The body of evidence documenting these disinformation wars continues to grow. The Computational Propaganda Project at the University of Oxford has been investigating the global disinformation order since 2012. Its latest report2, titled The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation, includes the finding that:

A handful of sophisticated state actors use computational propaganda for foreign influence operations. Facebook and Twitter attributed foreign influence operations to seven countries … who have used these platforms to influence global audiences.

The actions of the Internet Research Agency, a Russian organisation, clearly illustrate this.

A flood of fake news circulated through social media and on YouTube during the 2016 United States presidential election campaign. Then, in February 2018, the United States Department of Justice announced that a grand jury had returned an indictment charging thirteen Russian nationals and three Russian companies “for committing federal crimes while seeking to interfere in the United States political system, including the 2016 Presidential election.”

The indictment states that the Internet Research Agency,

a Russian organization engaged in political and electoral interference operations [had] sought, in part, to conduct what it called “information warfare against the United States of America” through fictitious U.S. personas on social media platforms and other Internet-based media.

Further, the very same Internet Research Agency has also been implicated in spreading disinformation with the aim of creating discord in society.

A May 2018 paper3 found that Russian trolls were political and divisive in regard to the vaccination debate in the United States, promoting discord:

#VaccinateUS tweets were uniquely identified with Russian troll accounts linked to the Internet Research Agency—a company backed by the Russian government specializing in online influence operations. Thus, health communications have become “weaponized”: public health issues, such as vaccination, are included in attempts to spread misinformation and disinformation by foreign powers.

While the Internet Research Agency may have been disarmed, it’s clear that other organisations have been quickly established to take its place. For example, in Australia’s recent bushfire crisis, the actions of social media accounts using the hashtag #ArsonEmergency bore a striking resemblance to the activities of the Internet Research Agency.

How to not become a mercenary

Despite the clear evidence, over the past week I’ve seen a number of my friends sign up as disinformation war mercenaries by sharing posts on Facebook without checking that what they are sharing is true. The Computational Propaganda Project has found that Facebook is the weapon of choice for the disinformation warmongers, stating4 that:

Despite there being more social networking platforms than ever, Facebook remains the platform of choice for social media manipulation. In 56 countries, we found evidence of formally organized computational propaganda campaigns on Facebook.

I’m sure I haven’t made myself popular with my friends by calling out their posts, but in times of war, we all need to be vigilant and act against threats to peace and stability when we see them.

One example of the disinformation I’ve seen shared is a video purporting to be of the market in Wuhan that is thought to have been the source of the current COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak, when the video actually shows the Langowan extreme animal market in Indonesia.

This video is being circulated despite warnings from experts and the World Health Organisation (WHO) of the serious dangers of an ‘infodemic’ of misinformation in regard to COVID-19, and the Facebook page that is the source of the video having a very obvious anti-China agenda.

Another example is a post that seeks to promote discord in regard to the debate over Australia Day, with the risk of causing harm to Australia’s Aboriginal people. I’ll use this post as a case study in how to avoid becoming a mercenary in the disinformation wars.

Australia Day is a national celebration held in Australia on the 26th of January each year. However, the event is very controversial, with many Aboriginal people instead calling the day Invasion Day because the 26th of January marks the day in 1788 that the First Fleet arrived from Britain and began the colonisation of what would later be called Australia.

The post that my friends shared is this one:

This post has attracted 1,100 likes, 735 comments, and 4,100 shares, and there are also other copies of it that have attracted large numbers of likes and shares.

However, the way the post is written should throw up some immediate red flags in regard to its authenticity, triggering some online research that will then reveal that it’s complete nonsense and full of lies:

- The first clue that the post is part of an organised disinformation campaign is that it begins with “A friend of mine posted this on their timeline. A very interesting read. There was no ‘share’ so I have copied and pasted as well.” This is deliberately designed to give the post an air of credibility, while at the same time ensuring that when the post is shared it can’t be traced back to the original source.

- Then the post seeks to hook the reader by playing to some popular views in society: notions that the media doesn’t tell the truth, that politicians aren’t working in our interest, that the education system is failing children, and that local councils are opposed to Australia Day.

- Finally, the post completes its confidence trick by putting forward an emotional argument saying that Australia Day was actually created to help benefit Aboriginal people, which is in reality completely untrue.

- A further red flag is the complete lack of any references to support the claims that have been made.

Once I’d seen these red flags, it led me to immediately check the information in the post against historical sources in the National Library of Australia’s Trove database. The post states that the 26th of January was chosen as the date for Australia Day because it celebrates the implementation of the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948. However, within just 15 minutes I was able to determine that:

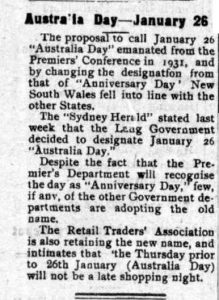

- The proposal to call 26 January Australia Day emanated from the Premier’s Conference in 1931, as shown in Figure 1 below, and was therefore not the result of the implementation of the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948.

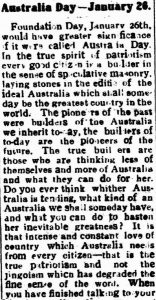

- This proposal came about in response to calls to rename what had been previously been known as “Foundation Day”, as shown in Figure 2 below.

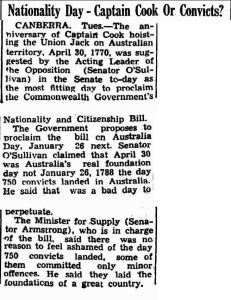

- Nearly 20 years later, Australia Day was chosen as the date to proclaim the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948, as shown in Figure 3 below. As Figure 3 reveals, even then some people were unhappy with this choice because the 26th of January commemorated the landing of the First Fleet.

Everyone needs to look for the red flags in the posts they see on Facebook, and investigate anything that is even slightly doubtful before sharing it. If we all do this, then the winner of the disinformation wars will be the truth.

Header image source: pxfuel, Public Domain.

References:

- Libicki, M. (1995). What Is Information Warfare? ACIS Paper 3, Washington, DC:National Defense University. ↩

- Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2019). The global disinformation order: 2019 global inventory of organised social media manipulation. Project on Computational Propaganda. ↩

- Broniatowski, D. A., Jamison, A. M., Qi, S., AlKulaib, L., Chen, T., Benton, A., … & Dredze, M. (2018). Weaponized health communication: Twitter bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. American journal of public health, 108(10), 1378-1384. ↩

- Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2019). The global disinformation order: 2019 global inventory of organised social media manipulation. Project on Computational Propaganda. ↩

Also published on Medium.

Nice article Bruce. The problem is that the friction of sharing is so much lower than the cost of actually reading and critically analysing the information that is put in front of us — and social media platforms have absolutely zero incentive to raise that bar.

Imagine how different our discourse would be if people had to go through a couple of extra hoops to share – even something as simple as confirming that you spent a minimum of 60 seconds reading a post before you could pass it on.

We need better ways to get past the endorphin rush and engage the critical thinking part of our brain online.