Australia’s public servants: dedicated, highly trained … and elitist

This article is part of a series of articles on stakeholder and community engagement.

Ron Levy, Australian National University

One of the limitations of popular rule is that the people can’t vote on every matter. Instead, faced daily with complex decisions on everything from the environment to aviation to foreign affairs, governments often take the lead. But governments still consult citizens in order to be guided by the people’s broad values and policy preferences.

That, at least, is the theory of how modern democracies function. And it is a useful theory: it preserves the notion that “the people” are still in charge.

However, I was recently part of a team of researchers who ran the Future of Australia’s Federation Survey. We received answers from nearly 2,000 state and federal public servants across Australia on a 39-point questionnaire. Our questions gauged, among other things, what really goes on when policy is made on citizens’ behalf. (I report on some of our results here.)

The picture that emerged was of a dedicated, highly trained and professional cadre of public servants. But some answers raised doubt about a genuine steering role for citizens in policy-making.

Our research found attitudes of elitism among public servants, which effectively led them to resist public input. The public servants’ animating assumption – often wrong – was that members of the general public lack the capacity to deliberate well on broad policy directions.

Future of Australia’s Federation Survey

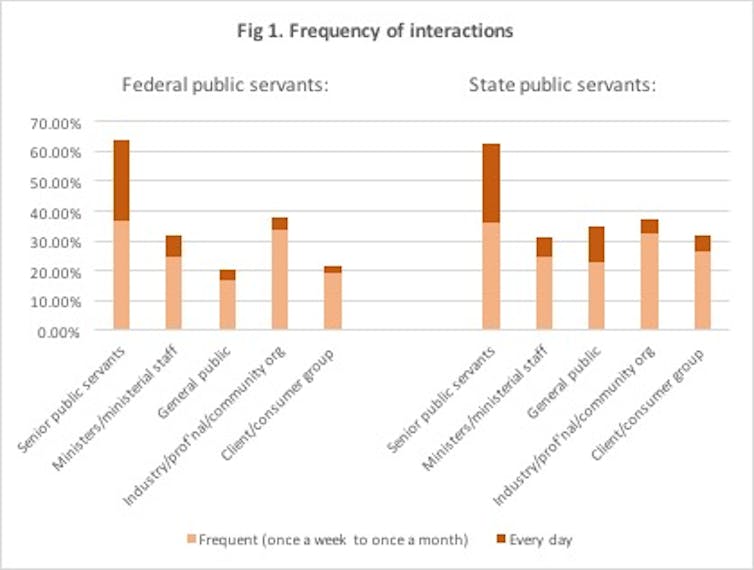

One of our questions asked “how much direct interaction” public servants “personally have with” an array of people in the course of their work. The answers showed that public servants deliberate, most of all, with other public servants.

Of course, public servants must interact with their colleagues when conducting their work. So these results do not necessarily preclude meaningful interaction with the public or its representatives. Indeed, many public servants – though a minority – also reported frequent interactions with the general public, or with industry and community groups, consumer groups and ministers or ministerial staff.

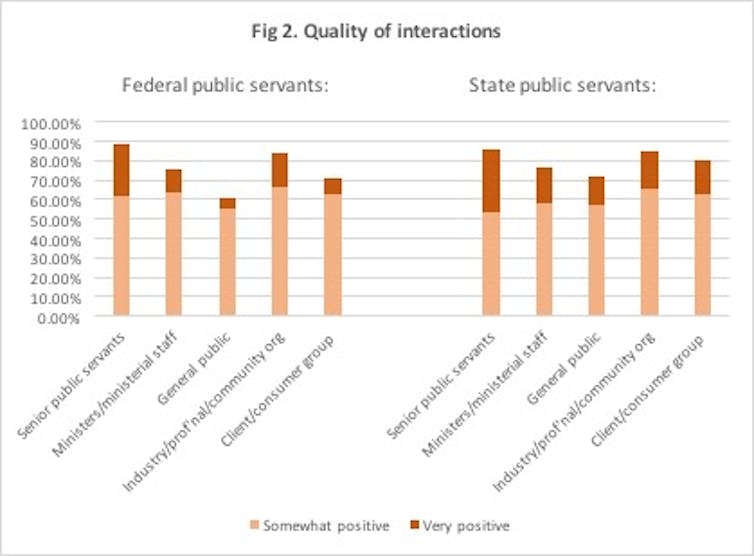

Our other survey questions looked at the quality of these interactions. The respondents most often held positive views of their interactions with other public servants. The next-most-positive were interactions with industry and community groups, consumer groups and ministries.

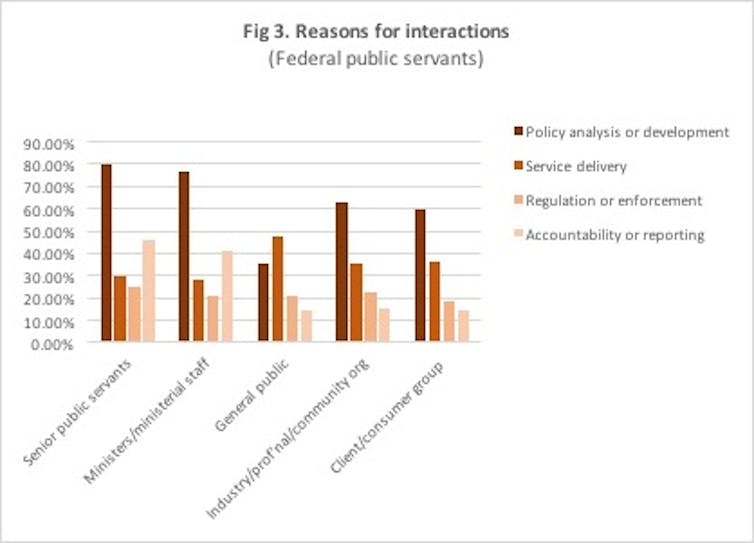

Interactions with members of the general public were less often described as positive. Moreover, the great majority of interactions with ordinary citizens were to deliver services, not to involve these citizens in policy-making.

One possible conclusion is that public servants remain amenable to ordinary citizens’ input in policy-making, but simply prefer that civil society groups or ministries first collect public views in more coherent and convenient forms.

But whether these groups really represent public views is questionable. This is clearest for groups that are actually wealthy and well-connected lobbying organisations – self-appointed influencers, rather than bona fide representatives of ordinary citizens.

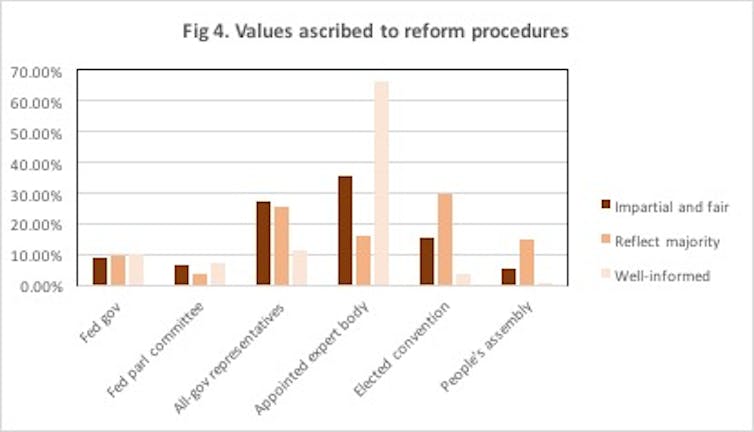

A last set of survey questions was the most telling. These asked public servants whether they thought ordinary citizens could ever deliberate well on a particular matter: constitutional reform.

We described well-established public deliberation methods that engage and inform ordinary citizens – for example, citizens’ assemblies like the one recently used in advance of the Irish abortion referendum.

But the public servants largely rejected this option. Most still preferred to see decisions made by elites like themselves.

Our results show that public servants hold unfavourable assumptions about deliberation by members of the general public. Our data thus raise doubts that members of the general public are considered welcome contributors in policy-making.

Why public service elitism matters

Why does all this matter? First, the idea that ordinary citizens can’t deliberate well contradicts some important empirical findings.

Members of the general public can often deliberate well – even often better than certain elites – if given institutional support to do so (such as information and opportunities for dialogue).

But most public servants presume the quality of ordinary citizen deliberation will always remain poor, regardless of institutional help.

Second, nearly all government policies – for example, how to mitigate climate change – require trade-offs between costs and benefits experienced by various societal groups. Some people stand to gain, while others lose after any policy change.

We should therefore reject the myth that policy-making is purely technical, legal or scientific, and can be conducted in a vacuum. Most policy-making has to rely in some way on consultation with citizens to determine what public values should steer policy.

![]() In short, our research found evidence that public servants do not act as democratic theorists might hope or predict. A clear democratic conduit between citizen and policymaker is largely absent. In part, this seems due to many public servants’ unjustified attitudes of elitism toward the ordinary citizens they purport to serve.

In short, our research found evidence that public servants do not act as democratic theorists might hope or predict. A clear democratic conduit between citizen and policymaker is largely absent. In part, this seems due to many public servants’ unjustified attitudes of elitism toward the ordinary citizens they purport to serve.

Ron Levy, Associate professor, Australian National University

Article source: This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.