The knowledge management implications of the Trump vote

This article is part of a series of articles on stakeholder and community engagement.

Media across the world reacted to the US Presidential election outcome with shock, disbelief and anxiety, saying that the world had fundamentally changed overnight. But did it? No, it didn’t, and this reaction shows a serious lack of knowledge of the current state of US society.

Writing in The Conversation, Clive Hamilton, Professor of Public Ethics in the Centre For Applied Philosophy & Public Ethics (CAPPE) at Charles Sturt University, reminds us that for many months it had been clear that over 40% of American voters were going to vote for Trump no matter what, and that the Trump win came down to just the 3% of voters who had been unwilling to reveal their voting intentions prior to the election.

Hamilton alerts to the deep divisions in US society that have been six decades in the making: “Over that time, the left won the cultural battle and the right won the economic battle, and Trumpism is a reaction against both.” As a result of neoliberal economics, “the wealthy are richer and more powerful. Billionaires and big corporations have greater influence over politics. Leaving things to the market has had a devastating impact of great swathes of middle America.” Trump’s message has resonated with these disaffected masses, whose anger is fueled by a deep sense of shame at being unable to support their families.

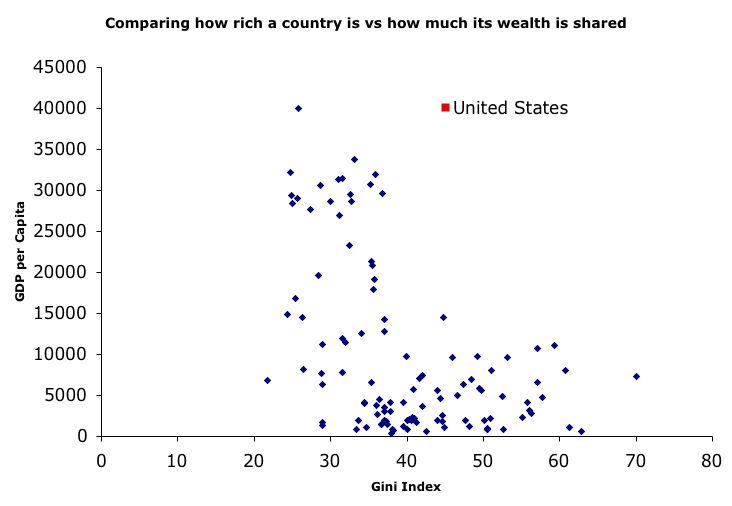

Wealth inequality in the US is actually truly exceptional. Professor David Pannell, Head of the School of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Director of the Centre for Environmental Economics and Policy at The University of Western Australia, provides an insight into this inequality. He advises that above a certain level of inequality, almost all countries have really low average income levels, while above a certain level of average income, almost all countries have fairly low inequality. The exception is the US, which has both high average income and high inequality. The starkness of the situation can be clearly seen in the graph below (Figure 1).

The wide disparities that also exist in Australia are discussed by ABC News Australia Business Editor Ian Verrender. He talks about the loss of jobs to productivity enhancing technologies over the past five decades, giving rise to an underemployed working class, and the disparity of returns for Australia’s many small shareholders: “small investors are angry that the spoils aren’t being shared anywhere near equally and that the pain is being disproportionately borne by those at the bottom.”

When people are experiencing personal shame as a result of economic disadvantage, it’s not surprising that they will seek to blame migrants, who they perceive as contributing to the problem by either taking jobs away from them or receiving more government support and benefits than they do. Trump captured this discord, as has the Brexit vote and Australia’s controversial politician Pauline Hanson.

Pauline Hanson lived in the city of Ipswich, located on the western outskirts of Brisbane, capital of the Australian state of Queensland. She was first elected to the Australian Parliament in 1996, appealing to disadvantaged white Australians by criticising what she saw as the more favourable financial treatment given to Aboriginal Australians and Asian immigrants. While these claims were grossly untrue, I can well understand her motivation for making them.

I lived in the city of Ipswich at the same time as Pauline Hanson, and was her regular customer at Marsden’s Seafoods, Hanson’s fish and chip shop on Blackstone Road. I saw her putting in long and hard hours of work as a single mother at a time when Ipswich was suffering a serious economic downturn after the closure of the city’s railway workshops and woolen mills and a decline in the coal mining industry that was the city’s other economic mainstay. Life would have been a financial struggle for Hanson, and for the many people who voted for her, just as it is for Trump’s supporters.

I would later experience the same community disenchantment with mainstream government when carrying out the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Project, as I discuss in the article Case studies in complexity (part 6): Tacit knowledge transfer and deliberative conversations in the Helidon Hills. After her election in 1996, Pauline Hanson established the One Nation political party which gained widespread electoral support in the economically disadvantaged rural areas where the Helidon Hills project was conducted.

Richard Sambrook, Professor of Journalism at Cardiff University, writes in The Conversation that the media got it so wrong with Trump (and Brexit) because “big media has too easily become part of the political/celebrity bubble and tends to forget that journalism is meant to be an “outsider” activity – outside the halls of power, but not outside the communities it serves.”

As Sambrook states, the media got it wrong because “Too much of the media spends too much time talking to itself and not to the communities it serves.” Converse to this, I got it right in the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Project because I spent as much time as possible talking with the community of the Helidon Hills area, listening to their stories and working with them collaboratively to develop plans that everyone could relate to.

If we are to move beyond the frustrations that have led to the election of Donald Trump and the Brexit vote, then the approaches I applied in the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Project need to be applied universally.

Postscript: On 26 January 2017, Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett published the article The Science Is In: Greater Equality Makes Societies Healthier which provides an in-depth analysis of wealth inequality in the United States.

See also: How the media is going to be, and has been, Trumped.

Header image source: Donald Trump at CPAC 2011 in Washington, D.C. Photo by Gage Skidmore is licensed by CC BY-SA 2.0.

Also published on Medium.