Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology [Personality & TKMS series]

This is part 8 of a series of articles featuring edited portions of Dr. Maureen Sullivan’s PhD dissertation.

Users of technical knowledge management systems (TKMSs) willingness to adopt the systems directly relates to their level of acceptance of the new technology. The technology acceptance model (TAM) outlines two issues of individual acceptance: usefulness and ease of use.

As a result, researchers developed several different models by studying these issues from various dimensions. Researchers Venkatesh and Davis1 believed that the perceived usefulness of an information system is affected by users‘ perception of their personal image and job importance. Consequently, Venkatesh and Davis revised the TAM to include social influence as a new construct and called the revised model TAM2. Thompson, Higgins, and Howell2 observed users‘ behaviors while they were using PCs and added two more variables to TAM2 that included the long-term effects of new technology and facilitating conditions.

TAM and TAM2 models were created to assist companies and organizations with understanding reaction to new technology by customers and employees. In addition, these models help companies focus on how employees would respond to new technology.

Conversely, due to limitations in some of the TAM and TAM dimensions and constructs, companies and organizations were prevented from fully listing the reasons why new technology was not accepted by customers or employees. Venkatesh et al.3 proposed an integrated model called the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) after examining eight well-known models.

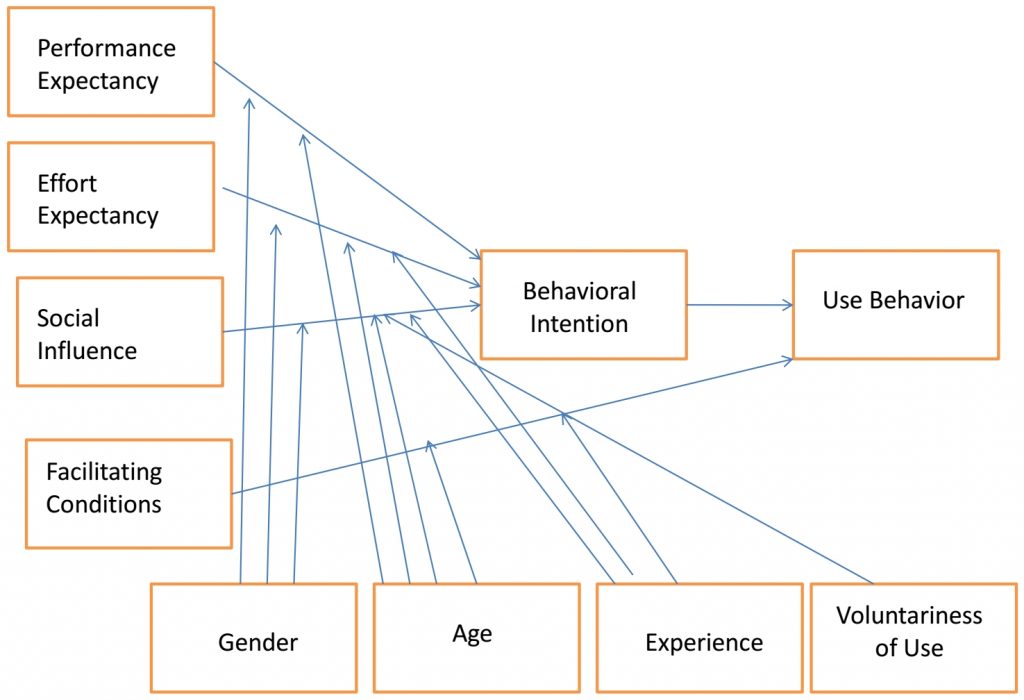

UTAUT consists of four constructs: facilitation conditions, efforts expectancy, performance expectancy, and social influence. These constructs were derived from the eight well-known models and directly addresses the intention of behavior to use technology. Figure 1 demonstrates this theory.

The four constructs of UTAUT defined by Venkatesh et al. are:

- Performance expectancy – The level a person considers that the use of a new technology would help to improve their work performance. This construct is included as perceived usefulness in TAM.

- Effort expectancy – The degree to which the user perceives the system as easy to use. This construct includes scale items from TAM.

- Social influence – The degree to which the user perceives that others who are important to the user believe that the user should use the system. The construct includes scales from subjective norms in TAM.

- Facilitating conditions – The degree to which the user believes that conditions are adequate for effective use of the system, including organizational readiness and infrastructure adequacy. This construct encompasses perceived behavior control, TAM and other variants.

Past research studies have used the UTAUT model to test a variety of areas involving the acceptance of technology. For instance, Robinson4 applied the UTAUT model to a study of students‘ adoption of technology in marketing education. Additionally, several researchers have performed studies that have validated the UTAUT model in Internet technologies and virtual communities5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 .

Further, Koivumaki, Ristola, and Kesti14 used the UTAUT model to study the adoption of mobile technology thereby adding to the literature on technology acceptance. This study added to the literature through the study of mobile technology. Further studies added more dimensions to the UTAUT that reflected the flexibility of the model. For instance, Wang, Wu, and Wang15 conducted a research study that included an additional dimension of self-management and perceived playfulness as independent variables moderated by age and gender. The study investigated age and gender as significant determinants to the adoption of mobile learning technology.

Despite its usefulness in studying the acceptance of technology, the UTAUT model is limited in that it does not include the task-technology fit (TTF). Venkatesh et al. noted that this was not included in the UTAUT model and that it warranted further research. Essentially, the models that underlie the UTAUT model fail to include task constructs. Typically, users intend to use information technology if it meets their task requirements. Dishaw, Strong, and Bandy16 conducted a study that added TTF constructs to the UTAUT with the goal of determining whether this addition produced an improvement in explanatory power, similar to that reported by Dishaw and Strong17. The results of their study produced a new model that combined the TTF and UTAUT models.

Next edition: Addressing generational differences in the adoption of technical knowledge management systems.

References:

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology

acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186-204. doi:10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926 ↩ - Thompson, R. L., Higgins, C. A., & Howell, J. M. (1991). Personal computing: Toward a conceptual model of utilization. MIS Quarterly, 15(1), 125-143. doi:10.2307/249443 ↩

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425-478. ↩

- Robinson, J. L. (2006). Moving beyond adoption: Exploring the determinants of student 150 intention to use technology. Marketing Education Review, 16(2), 79-88. ↩

- Anderson, J. E., Schwager, P. H., & Kerns, R. L. (2006). The drivers for acceptance of tablet pcs by faculty in a college of business. Journal of Information Systems Education, 17, 429-440. ↩

- Chieh-Peng, L., & Anol, B. (2008). Learning online social support: An investigation of network information technology based on UTAUT. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(3), 268-272. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.0057 ↩

- Debuse, J. C. W., Lawley, M., & Shibl, R. (2008). Educators’ perceptions of automated feedback systems. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 24(4), 374-386. ↩

- Hennington, A. H., & Janz, B. D. (2007). Information systems and healthcare XVI: Physician adoption of electronic medical records: Applying the UTAUT model in a healthcare context. Communications of AIS, 2007(19), 60-80. ↩

- Lin, H. F., & Lee, G. (2006). Determinants of success for online communities: An empirical study. Behaviour & Information Technology, 25(6), 479-488. doi:10.1080/01449290500330422 ↩

- Loke, Y. J. (2008). Merchants and credit cards: Determinants, perceptions and current practices: A case of Malaysia. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 13(2), 121-134. doi:10.1057/fsm.2008.15 ↩

- Pappas, F. C., & Volk, F. (2007). Audience counts and reporting system: Establishing a cyber-infrastructure for museum educators. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(2), 752-768. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00348.x ↩

- Park, J. K., Yang, S. J., & Lehto, X. R. (2007). Adoption of mobile technologies for Chinese consumers. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 8(3), 196-206. ↩

- Wang, Y. S., Hung, Y. H., & Chou, S. C. T. (2006, November 20-22). Acceptance of egovernment services: A validation of the UTAUT. Paper presented at the WSEAS Conference on E-Activities, Venice, Italy. ↩

- Koivumaki, T., Ristola, A., & Kesti, M. (2008). The perceptions towards mobile services: An empirical analysis of the role of use facilitators. Personal & Ubiquitous Computing, 12(1), 67-75. doi:10.1007/s00779-006-0128-x ↩

- Wang, Y. S., Wu, M. C., & Wang, H. Y. (2009). Investigating the determinants and age and gender differences in the acceptance of mobile learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(1), 92-118. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00809.x ↩

- Dishaw, M., Strong, D., & Bandy, D. B. (2004). The impact of task-technology fit in technology acceptance and utilization models. AMCIS 2004 Proceedings. Paper 416, New York, NY. ↩

- Dishaw, M. T., & Strong, D. M. (1999). Extending the technology acceptance model with task-technology fit constructs. Information and Management, 36(1), 9-21. doi:10.1016/S0378-7206(98)00101-3 ↩