Taking responsibility for complexity (section 2.2): Why does complexity matter in implementing policies and programmes?

This article is section 2.2 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems.

Complex problems and the challenges they pose. This section [Section 2] should enable the reader to assess whether their implementation challenge is in fact a ‘complex’ problem, and to identify key characteristics to mark out the appropriate tools for managing the type of complexity faced. It first describes what is meant by a complex problem, and then outlines three specific aspects of complex problems that cause problems for traditional policy implementation. It goes into detail on each of these aspects, providing explanations and ideas to help the reader identify whether their policy or programme is complex in this way (Sections 2.3-2.5).

2.2 Why does complexity matter in implementing policies and programmes?

The main argument of this section, and a central argument to this paper, is that different types of issue require different approaches to designing and implementing policies and programmes. However, there are some particular features of complex problems that explain why they present particular challenges in implementing programmes and policies. In this regard, a broad body of research has categorised different types of policy issue into three dimensions:

- For some problems, the capacity to act can come from well-defined, smoothly operating hierarchies; others cannot be controlled by one actor and involve distributed capacities and a variety of dynamics at different levels, with ongoing negotiations between them.

- For some issues, there is relatively stable knowledge on cause and effect, or the means for addressing issues; this is less well-understood or straightforward for other issues, which are quite unpredictable.

- For some issues, there is consensus on the questions policy must address, or the goals it must work towards; in others there are many plausible and equally legitimate interpretations and perspectives.

The different approaches needed for different types of problems relate to these dimensions1, which are essentially about when, where and how knowledge should be linked to decision-making for implementation. The first is about where decision-making action takes place, and what levels are linked to knowledge (e.g. national vs. local level). The second is about when we gain important knowledge about action, and when crucial decisions must be made (e.g. before an intervention vs. during it). The third is about how decision-making can fruitfully take place and how knowledge should be integrated (e.g. instrumental and technocratic vs. dialogue-based).

Complex problems are those best characterised by the latter option for any of the three dimensions above: there is 1) limited knowledge of different levels and distributed capacities; 2) limited knowledge of cause and effect and high unpredictability; or 3) limited consensus on the questions for policy to address or the overarching goals2. For complex problems, there are limitations and challenges in linking knowledge with implementation: limited knowledge of different scales, limited knowledge of the future and limited understanding in the face of conflicting perspectives.

Meanwhile, ‘traditional,’ well-established and strongly embedded approaches to implementation rely on the policy problem involving stable hierarchies, well-understood causality and agreed policy goals. For example, taking action through regulation and legislation, standardising solutions and importing best practices is suitable where there is consensus on the goals of policy and on the means of addressing it (so-called ‘well-structured problems,’ 3, or the domain of the ‘known’ 4). Alternatively, a technocratic response employing selected scientific inputs for analysis to improve services is appropriate where there are agreed goals but causal relationships are not fully understood (‘moderately structured’ problems, or the domain of the ‘knowable’)5.

When traditional approaches are applied to complex issues, they are based on inappropriate assumptions. They assume that knowledge and policy implementation can be linked in a straightforward, linear manner. Below, we go into each of the three dimensions in turn, outlining the nature of complex issues according to the dimension, as well as the problems and side-effects of applying a traditional approach to implementation in each case. But a general argument can be made first. Where tools, structures and approaches for policy implementation rest on the mistaken idea that a complex problem is not complex, this will often mean these tools are irrelevant. The exercise of shoehorning a problem of one type into the shoe that fits another type of problem is of limited utility, as important aspects are systematically missed or ignored.

This not only wastes time and money, but also means the reality of implementation can become quite different from what is explicit in the various frameworks and structures – and processes become quite difficult for ‘outsiders’ to understand. In the face of complex problems, there is often a heightened emphasis on traditional linear and rational tools, on ensuring more rigorous targets, carrying out more in-depth reviews of scientific literature and focusing on measures to enable managers to keep a tighter watch on implementation. These reforms, intended to help improve practitioners work, seem to take them away from it instead, and seem to be driving an increasing ‘dissonance between what [aid workers] do and what they report that they do’ 6. Staff are often involved in managing a system of representation and interpretation of information as much as the projects themselves7. Natsios8 reports a widening divide between those involved in development programming and those charged with managing and supporting it.

Worse, than this, tools that are perfectly suitable for some problems have serious side-effects when applied to complex problems. Where incentives for staff are aligned around assumptions that problems are simple, this can lead to them being pushed towards aspects of the problem that suit these assumptions – focusing on the ‘low-hanging fruit’ and working with high risk aversion, which are both likely to lead (in the long run) to irrelevant programming in the face of complexity. These kinds of observation have been made elsewhere, and mark the cornerstone of the New Synthesis Project, a collaborative approach to developing a new framework for public administration that is suitable for complexity (see Box 2).

Box 2: The New Synthesis Project

The New Synthesis Project (NS6) is an international partnership of institutions and individuals dedicated to advancing the study and practice of public administration. It draws on the knowledge and experiences of senior public officials, researchers and scholars in Australia/New Zealand, Brazil, Canada, the Netherlands, Singapore and the UK to integrate key traditions and conventions and develop a unifying frame of reference for modern public administration.

It starts from the following proposition: ‘public administration as a practice and discipline is not yet aligned with the challenges of serving in the 21st century. This gap has generated risk aversion in public organisations at a time when innovation and creativity in government are most needed. It has acted as a barrier to change as the remnants of the previous frame of reference limit the capacity of the state to address an increasing number of complex public policy issues in the context of our global economy, networked society and fragile biosphere.’

NS6 argues that most practitioners know from experience that the ‘classical’ model of public administration, and New Public Management, do not adequate reflect the reality of current practice, and instead speak to only a declining fraction of their work. However, an updated frame of reference is lacking.

NS6 is looking to provide a narrative supported by powerful examples to help practitioners face the challenges of the 21st century. It is drawing on many new concepts about complexity, networks, resilience, adaptive systems and collective intelligence, as well as from new ideas in fields traditionally associated with public administration, such as political science, law, administrative and management sciences and organisational behaviour.

Source: www.ns6newsynthesis.com [archived].

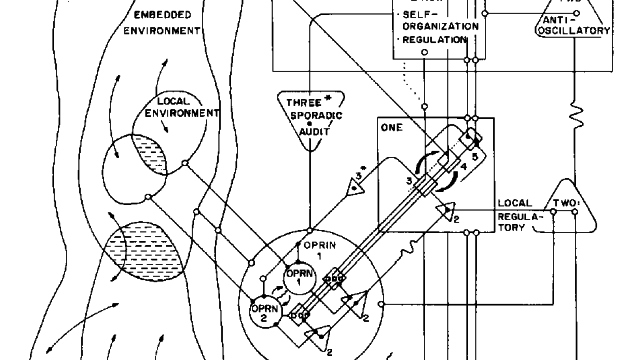

The next subsections explore these issues for each dimension in more detail. Before that, one caveat is important. Many of these insights are not in themselves new, with various areas of theory and practice touching on them for some time. However, approaching them from the starting point of ‘complexity,’ and drawing on the tools from complexity sciences, has brought out similarities between analyses and provided new ways of understanding the underlying issues. For example, agent-based modelling (ABM) has brought new ways of getting a handle on how micro-level behaviours relate to macro-level patterns, through the study of emergence and self-organisation. Application of ABM is rising in the social sciences to understand how different combinations of micro-level incentives and interactions can produce macro-level phenomena, helping economists and others to look into the implications of more complex assumptions; when combined with empirical data, it provides a valuable tool for testing and falsifying theories9. This is helping to bring factors such as trust, ownership and local knowledge into the mainstream of economics and other social sciences, providing a legitimacy previously dismissed by those with a more quantitative bent. It is also bringing together common themes in areas not systematically linked before, and promising to enrich our understanding on how to intervene in these processes to support development.

Next part (section 2.3): Where problems can be tackled: distributed capacities and intelligence.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity.

Article source: Jones, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 330. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6485.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

References and notes:

- Hogwood, B. and Gunn, L. (1984). Policy Analysis for the Real World. Oxford: OUP. ↩

- Some attempts to categorise policy problems have not included the first of these three dimensions, and have labelled complex problems as those that have both no stable knowledge on cause and effect and no consensus on the goals of policy – for example, others have labelled these problems the ‘domain of complexity’ (Kurtz and Snowden, 2003) or a matter of unstructured or badly structured problems (Hisschemoller and Hoppe, 2001). This paper attempts to build on these analyses and has benefited greatly from the insights provided there – however, the following two judgements are made: 1) the issue of scale and distributed intelligence is a crucial dimension of complex problems irreducible to the other two dimensions. Despite being tackled explicitly and implicitly in much of the work on complexity, it is not incorporated into any of the problem taxonomies; 2) for the reasons presented below, issues that fall on the latter side of the spectrum for any of the three dimensions all present challenges for traditional policy approaches, and each has alternative approaches related to it. Also, the three issues are often interlinked, so complexity assigned according to one dimension may be linked to another. For example, with a variety of different actors required to negotiate policy responses, achieving consensus on policy goals is likely also to be an issue. Therefore, it is possible that it is better to consider complexity as a matter of degree, and to cover issues that have the latter designation for any one of the three rather than requiring a complex problem to meet all three. ↩

- Hisschemoller, M. and Hoppe, R. (2001). ‘Coping with Intractable Controversies: The Case for Problem Structuring in Policy Design and Analysis.’ In Hisschemoller, M., Hoppe, R., Dunn, N. and Ravetz, J. (eds). Knowledge, Power and Participation in Environmental Policy Analysis and Risk Assessment. New Brunswick: Transaction. ↩

- Kurtz, C.F. and Snowden, D. (2003). ‘The New Dynamics of Strategy: Sense-making in a Complex and Complicated World.’ IBM Systems Journal 42(3): 462-483. ↩

- Shaxson, L. (2009). ‘Making Sense of Wicked Issues: Do Policy-makers Have a Suitable Toolkit?’ Presentation to DEFRA. ↩

- Eyben, R. (2010). ‘Hiding Relations: The Irony of “Effective Aid.”’ European Journal of Development Research (22)3: 382-397. ↩

- Mosse, D. (2006). ‘Anti-social Anthropology? Objectivity, Objection and the Ethnography of Public Policy and Professional Communities.’ Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 12(4): 935-956. ↩

- Natsios, A. (2010). The Clash of the Counter-bureaucracy and Development. Washington, DC: CGD. ↩

- Janssen, M.A. and Ostrom, E. (2006). ‘Empirically based, Agent-based Models.’ Ecology and Society 11(2): 37. ↩