Taking responsibility for complexity (section 3.2.1): Appropriate planning

This article is part of section 3.2 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems.

Although strategy and planning are still desirable and relevant in the face of uncertainty, it is crucial to ensure that levels of uncertainty and ambiguity are accepted as a de facto part of the policy-making process. There are some straightforward implications of this: light and flexible systems around ex ante analysis are needed to facilitate responsive, appropriate interventions. For example, taking the lead in convening a group of actors may require some commitment of funds, although the precise nature of the policy solution that will be agreed may not be decided until further down the line.

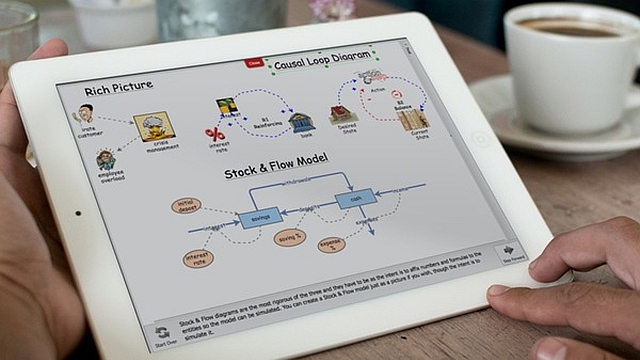

In complex problems it is still worthwhile carrying out ex ante analyses of a problem, its causes, its consequences and its contextual setting, but this should be based on lessons about what is effective in shaping successful projects on the specific problem. For example, environmental impact assessments (EIAs) are often embedded in national laws, and compulsory for set types of projects (those that are, based on experience, likely to have significant environmental impact). There is some flexibility over smaller projects or ones where the environmental impact is less easy to predict in advance. It may be useful to generate certain ‘do no harm’ tools for certain sectors, to help minimise potential negative impacts on certain outcomes that may otherwise be forgotten or poorly understood.

Ex ante assessment and planning tools may be aimed predominantly at enhancing the knowledge, awareness and capacities of decision-makers through the process of carrying them out, rather than being attempts to map out the future. For example, Drivers of Change was developed within the UK Department for International Development (DFID)1, motivated by the fact that donor organisations frequently explained away the failure of their programmes by pointing to a lack of political will for change among aid recipients, without examining the underlying reasons for this lack of will. This can be used as a learning exercise to enable a better appreciation of the interlocking causes that make progressive change so difficult in some of the poorest developing countries.

The locus of accountability should shift away from fixing detailed action plans and budget allocations before intervening: it is better to embed flexibility and adaptation in order to allow interventions to react to ongoing learning and unexpected conditions, so there must be space to improvise2. One way of doing this is to provide core funding to trusted units or partners with a proven track record and/or seed funding to those with potential, and giving resources based on intuitively developed plans with broad outcomes in order to allow project/programme staff to adapt to unfolding circumstances3.

Another way of doing this is to anchor accountability to clear principles for action (‘if, then’-type statements), providing a benchmark to measure performance against which does not make action inflexible. US marine operations work according to three such principles, which govern decisionmaking in complex and unpredictable environments: 1) capture the high ground; 2) stay in touch; and 3) keep moving. In this way, decentralised decision-makers can be very clear about the principles to which they will be held accountable, while having principles rather than set plans enables adaptive responses to emerge4. As mentioned earlier, holding teams or organisations to account for functional roles, or to clear statements of missions or values, is one way of doing this.

Another way of doing this is to build in rules for the adjustment of plans in advance. Planning processes will need to look at likely variations in future conditions that will affect the operation of the policy, ask how it will need to be adjusted and predefine this adjustment5. During implementation, there must be monitoring of the key indicators, which will trigger the appropriate adjustment when needed. Alternatively, processes for review and evaluation could be triggered based on threshold values of certain outcomes that are monitored, or stakeholder feedback and the availability of critical new information. This can feed back into policy by recommending adjustments to make it robust across a range of newly anticipated conditions, developing indicators that will trigger future (predefined) adjustment or triggers for future analysis.

Next part (section 3.2.2): Iterative impact-oriented monitoring.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity.

Article source: Jones, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 330. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6485.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

References and notes:

- Booth, D., Cammack, D., Harrigan, J., Kanyongolo, E., Mataure, M. and Ngwira, N. (2006). ‘Drivers of Change and Development in Malawi.’ Working Paper 261. London: ODI. ↩

- Pina e Cunha, M. and Vieira da Cunha, J. (2006). ‘Towards a Complexity Theory of Strategy.’ Management Decision 44(7): 839-850. ↩

- Reeler, D. (2007). ‘A Three-fold Theory of Social Change; and Implications for Practice, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation.’ Cape Town: CDRA. ↩

- Ramalingam, B. and Jones, H., with Reba, T. and Young, J. (2008). ‘Exploring the Science of Complexity: Ideas and Implications for Development and Humanitarian Work.’ Working Paper 285. London: ODI. ↩

- Swanson, D. and Bhadwal, S. (eds) (2009). Creating Adaptive Policies: A Guide for Policy Making in an Uncertain World. Winnipeg and Ottawa: IISD and IDRC. ↩