Taking responsibility for complexity (section 3.3.3): Realistic foresight

This article is part of section 3.3 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems.

For aspects of interventions that do have to be fixed in advance – often high-level goals or balances of investment – planning processes must be creative, evidence-informed and based around methods that are appropriate to the context of complex problems. Despite unavoidable uncertainty, decisions do often have long-term consequences, and future alternatives require present-day choices. Forward thinking is often preferable to crisis management, and may not preclude the need to monitor environments closely; rather, it may help make an organisation or programme more nimble when the time comes for action.

An area that has been a major strategic concern for private sector organisations for decades, for Singapore for many years, for the UK policy environment for the past 10 years and increasingly for the public sector elsewhere relates to ‘foresight’ and futures techniques1. This is a well-developed field of practical and theoretical work which focuses on ‘the ability to create and maintain viable forward views and to use these in organisationally useful ways’ (emphasis added)2.

There are a variety of tools serving a variety of purposes. For example, horizon scanning and trend/driver analysis help teams look for challenges and opportunities; scenarios and visioning focus on assessing future social, political and economic contexts; roadmaps and backcasting help to define ideal actions; and models and simulations help to explore the dynamics of future options3. One key insight for applying futures techniques is that it is essential to draw on a range of perspectives from a variety of stakeholders, in order to ensure sufficient creativity and to avoid the problems of ‘group think’ 4.

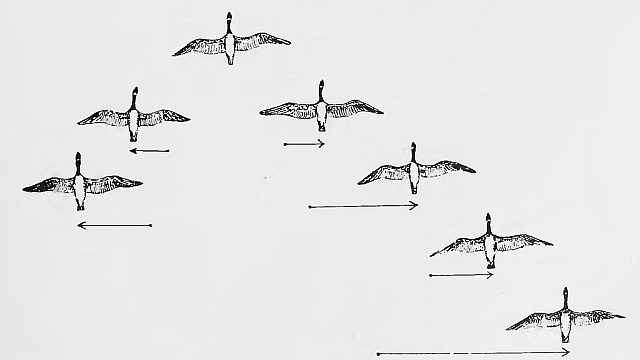

To better understand the potential, we look at one tool in particular. Scenario planning involves developing detailed pictures of plausible future worlds, constructed to encompass a broad span of possible futures, in order to ensure plans will cope with the many different ways in which the future could pan out. Against these scenarios, informed judgements can be made to produce decisions and policies that are robust under a variety of circumstances. If planning processes first identify the key contextual factors that will affect policy performance, then a series of possible scenarios can be developed as to how these factors might evolve. Proposed options can be ‘wind tunnelled’ against these to make it possible to explore how the policy will be affected if/when these change. Box 11 presents a recent example of tools for using scenario planning in development work.

Box 11: The pro-poor scenario toolkit

The Institute for Alternative Futures and the Rockefeller Foundation have developed a ‘pro-poor scenario toolkit,’ intended to provide guidance for learning and decision-making in the face of high uncertainty, placing poor populations at the centre of concerns for the future. It takes an ‘aspirational futures’ approach, which charts the future into three different zones:

- A zone of ‘conventional expectation,’ reflecting the extrapolation of current trends;

- A zone of ‘growing desperation,’ proposing a problem-plagued future embodying a group’s greatest fears and concerns;

- A zone of ‘high aspiration’ – a future characterised by surprising successes.

The toolkit provides guidance in facilitating scenario development and is at www.altfutures.org/pro_poor.

Scenarios and futures techniques encourage a move away from looking for ‘optimal’ policies or strategies: ‘any strategy can only be optimum under certain conditions,’ and ‘when those conditions change, the strategy may no longer be optimal’ 5. As such, it may be preferable to produce strategies that are robust to future variability rather than optimal for one possible future scenario. This could be seen as a ‘possibility space’ in which the future will unfold, allowing a programme to give a balanced evaluation of a range of strategies. Scenarios have also been found to improve understanding of the dynamics of change, to give clues and signposts about the timing and nature of key moments of change and to enable perception of a wider range of strategic opportunities than might otherwise emerge6.

Next part (section 3.3.4): Peer-to-peer learning.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity.

Article source: Jones, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 330. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/6485.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

References and notes:

- Bochel, H. and Shaxson, L. (2007). ‘Forward-looking Policy Making.’ In Bochel, H. and Duncan, S. (eds)Making Policy in Theory and Practice. Bristol: The Policy Press. ↩

- Slaughter, R. (2003) ‘Futures Concepts.’ Briefing Paper for Christian Futures Consultation. ↩

- Ramalingam, B. and Jones, H. (2007). Strategic Futures Planning: A Guide for Public Sector Organisations. London: Ark Group Publishing. ↩

- Ramalingam, B. and Jones, H. (2007). Strategic Futures Planning: A Guide for Public Sector Organisations. London: Ark Group Publishing. ↩

- Mittleton-Kelly, E. (2003). ‘Ten Principles of Complexity and Enabling Infrastructures.’ In Complex Systems and Evolutionary Perspectives of Organisations: The Application of Complexity Theory to Organizations. London: Elsevier Press. ↩

- Ralston, B. and Wilson, I. (2006). The scenario planning handbook: Developing strategies in uncertain times. United States: Thompson-Southwestern. ↩