Managing in the face of complexity (part 3.2): A. Move from static to adaptive management

This article is part 3.2 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper A guide to managing in the face of complexity.

In the face of complexity, managing should neither be reduced to mechanistic implementation of pre-defined plans nor to engaging in ad hoc ‘trial and error’ testing of what works. Managing requires different approaches that acknowledge the limits to prediction and control and adapt to unfolding realities. In short, be open for learning and adaptation (this corresponds to the adaptive approach to planning in the face of complexity outlined in … [the planning and strategy development in the face of complexity series]1). [Part 4] … contains Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) as a recent example of the growing number of adaptive management approaches (Booth, Eoyang/Holladay, Heifetz, Manzi, Rondinelli, Pritchett et al).

Express and test a theory of change

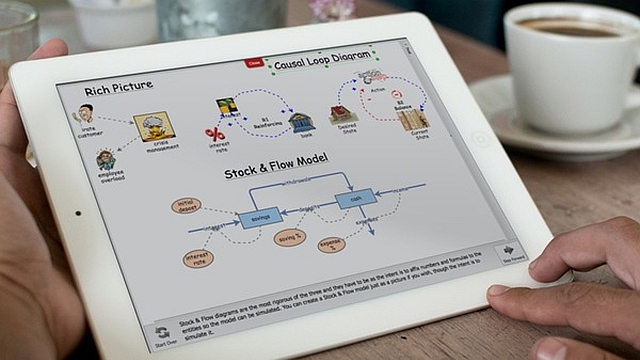

Essential to this shift is to see your intervention as an expression of hypotheses and assumptions. At the same time as attempting to produce deliverables or to achieve goals, your intervention is putting to the test ideas about how to best do this, i.e. positing theories of change and of action. This means that a central part of managing well is understanding the relevance and validity of those ideas.

Monitoring is a key management tool in order to test hypotheses and theories of change; learning-based processes and the purposeful and systematic pursuit of knowledge need to be an explicit part of management. On-going monitoring is the best tool to carry out this function by measuring, assessing and interpreting the effects an intervention is having. In particular, monitoring should focus on the key assumptions and hypotheses about how the intervention will have impact – this information should be used to adapt and refine the theory of change and the intervention itself.

Experiment to learn

Promoting experimentation and innovation is one way to ensure that development interventions can be rich learning exercises. As well as taking an opportunistic approach to learning, ‘active adaptive management’ promotes learning by doing by deliberately intervening in the system, in order to test hypotheses and generate a response that will shed light on how to address a problem. This is not quite as simple as management by ‘trial and error’, which might be inefficient and can hinder the institutionalisation of experience. However, there could be some small-scale interventions that are ‘safe-fail’, i.e. it is acceptable for them to fail2. Learning gained from a ‘failed’ project should be valued highly; and expecting a certain level of ‘attrition’, and ensuring sufficient redundancy should be seen as the only responsible approach to programming in complex domains. Unfortunately, the concept of pilots being allowed to fail, or agencies valuing bureaucracies is somewhat at odds with the current culture in development agencies – this point will be picked up again in the concluding section.

Incentivise learning

Carrying out good monitoring is more to do with leadership and communication than it is with the analytical tools used for the task. In the face of complex problems, actors are more likely to respond to evidence where it emerges in the context of trust and ownership. Monitoring functions must be embedded throughout implementation chains, with autonomy to shape M&E frameworks at different levels. Incentives are also important: when things that don’t go to plan are seen as a ‘failure’, staff are unlikely to reflect genuinely on issues. An alternative approach is to see an opportunity for learning in a project which seems to be underperforming – for example, triggering additional support and expertise. There may need to be a shift in accountability practices. Rather than being judged by results alone, in the face of uncertainty managers should set in place learning objectives alongside performance goals – this has also proven beneficial on staff motivation and productivity in the face of complex problems3.

Next part (part 3.3): B. Move from directive to collaborative management.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Taking responsibility for complexity.

Article source: Hummelbrunner, R. and Jones, H. (2013). A guide to managing in the face of complexity. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8662.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: pxhere, Public Domain.

References:

- Hummelbrunner, R. and Jones, H. (2013). A guide to planning and strategy development in the face of complexity, ODI Background Note. London: Overseas Development Institute. ↩

- Snowden, D. (2010). ‘Safe-fail Probes.’ Cognitive Edge network blog, 17 November 2007. https://cognitive-edge.com/blog/safe-fail-probes/ ↩

- Ordonez, L., Schweitzer, M., Galinsky, A. and Bazerman, M. (2009). ‘Goals Gone Wild: The Systematic Side-effects of Over-prescribing Goal-setting.’ Working Paper 09-083. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School. ↩