Managing in the face of complexity (part 4.1): Appropriate approaches – 1. Cynefin framework

This article is part 4.1 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper A guide to managing in the face of complexity.

This section [parts 4.1 to 4.8 of the series] outlines specific methods that can be used for managing in the face of complexity. Most of these approaches were originally developed in corporate business, where the shortcomings of centralised ‘command and control’ models were first noted, but have since spread into public sector management. These approaches are aligned with the general principles for managing complex interventions outlined … [in the previous parts of this series], but each has a specific focus and is tailored for particular circumstances or purposes.

1. Cynefin framework

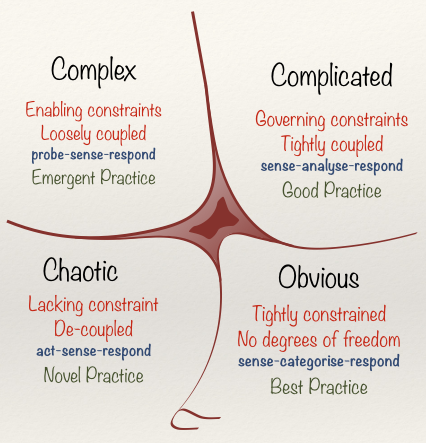

Widely discussed in international development, this is probably the most refined contingency approach to management. Developed by Snowden and Kurtz1, it offers a framework for deciding on the appropriate managerial style and is based on the distinction between simple, complicated and complex situations outlined in Box 1; it also adds ‘chaotic’ as a fourth dimension. Figure 1 summarises the management responses to each different level of complexity.

Simple[ / Obvious / Clear] situations:

Simple[ / Obvious / Clear]3 situations correspond to low uncertainty and low divergence. The management style most appropriate to simple situations is to:

- Sense: collect sufficient data to identify the core characteristics of a situation (e.g. what is required to carry out a specific task)

- Categorise: identify whether these characteristics apply to the given context (e.g. are the known requirements for action in place in the current situation)

- Respond: pick the best practice response to that category.

Since simple situations are largely independent of context, copying ‘best practice’ (i.e. applying solutions from one situation to another) is the most effective and efficient way to manage them.

Complicated situations:

Complicated situations correspond to high uncertainty and low divergence. The management style most appropriate to complicated situations is to:

- Sense: collect sufficient data to identify the core characteristics of the situation

- Analyse: deliberate on the information collected and use expertise from other contexts to choose appropriate responses (e.g. identify additional people, information or skills needed to carry out the task)

- Respond: apply this knowledge to the current situation and pick the most appropriate option.

Because situations are context sensitive and can be framed from different perspectives, careful analysis and comparison of characteristics is key. ‘Good practice’ (i.e. modifying the application of approaches from one situation to another context) is the most appropriate approach.

Complex situations:

These correspond to high uncertainty and high divergence. The most appropriate management style is to:

- Probe: design a few small-scale actions to test out ideas before taking full-fledged action

- Sense: collect sufficient data to identify the patterns of behaviour that could be a consequence of the probe and select what seems to be the right thing to do

- Respond: enhance the patterns that are desirable and dampen those that are leading the situation into undesirable behaviours.

Before adopting a course of action, you need first to better understand behaviour patterns over time. Emergent practice (i.e. practice that is gained from experimenting within a situation) is the most effective and efficient management approach, even though it can be quite demanding in terms of resources and time.

Chaotic situations:

These correspond to low uncertainty and high divergence faced. The most appropriate management style is to:

- Act: implement a strong response designed to shock the situation back into some form of order, or at least quickly curb negative consequences

- Sense: collect sufficient data to identify the patterns of behaviour that could be a consequence of that first action

- Respond: based on the results of the first action, enhance the patterns that are desirable and dampen any patterns that are leading the situation in the wrong direction.

In a chaotic situation there are neither observable patterns nor previous experience to rely on: anything can happen for almost any reason. Novel practice is required, often fast, but it must be developed from experience based on the observed outcomes of a determined action (one that has hopefully moved the situation in a positive direction).

It is important to note that these four dimensions are not distinct, mutually exclusive categories: they are located along a continuum with imprecise and permeable boundaries. Different perceptions of the degree of complexity of a situation may arise from disagreement on where the boundaries between simple, complicated, complex and chaotic situations lie. This has several important implications for working with this framework:

- Since managing simple situations is less resource intensive than managing more complex ones, it can be useful to consider moving a situation into an adjacent, less resource intensive domain (complex to complicated; complicated to simple). So instead of figuring out the most suitable way of managing the situation in terms of its existing zone it might actually be more effective to cross the boundary and manage a complicated process as if it were simple. This is something that we are already accustomed to in other areas, either by learning routines and rules (e.g. driving a car) or by using ‘checklists’ to guide us through complicated procedures (e.g. vehicle maintenance).

- Using these dimensions in collaborations can help understand different perspectives: for instance, when two actors locate the same situation in two different domains it reveals something about their underlying mental models. In this way, you can generate insight into how to manage such a situation across a partnership.

- It is not helpful to view a situation as entirely complex, or entirely simple. Most situations demonstrate features of all three (sometimes four) and while subcomponents of an issue may be simple, collectively they could add up to a complex problem. Therefore these distinctions should be used to understand certain aspects of a situation rather than the entire intervention. Think of an immunization program in rural areas that has already been carried out several times: there will be things that are quite certain (simple), like how many people clinic staff can immunise per day; and others that are rather uncertain (complicated or complex), such as other factors that may affect local people’s ability to attend clinics. And if crucial conditions change dramatically (e.g. an outbreak of violence) some things might turn chaotic.

Next part (part 4.2): Appropriate approaches – 2. Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA).

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Taking responsibility for complexity.

Article source: Hummelbrunner, R. and Jones, H. (2013). A guide to managing in the face of complexity. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8662.pdf). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: pxhere, Public Domain.

References and notes:

- Kurtz, C. F., & Snowden, D. J. (2003). The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world. IBM systems journal, 42(3), 462-483. ↩

- Figure 1 has been updated from the earlier version in A guide to managing in the face of complexity to this most recent version. ↩

- From 2014, after the publication of A guide to managing in the face of complexity, Snowden called the ‘simple’ domain ‘obvious’. The name of this domain has recently changed again to ‘clear’. ↩