Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity series (part 4): Task 2 – Assess the level of agreement

This article is part 4 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Background Note A guide for planning and strategy development in the face of complexity.

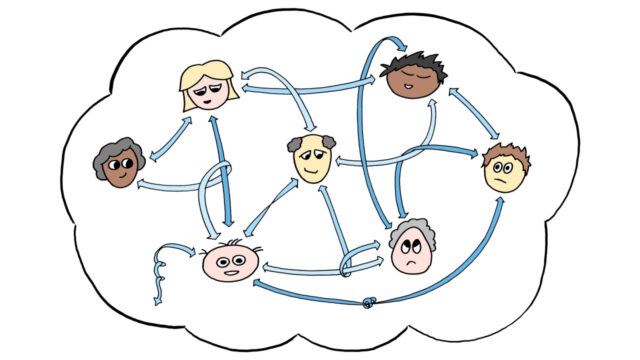

Next we need to assess the extent to which there is agreement or divergence about the problem, about what to do (goals as well as the strategy to reach them) – or about both. When it comes to multi-dimensional issues faced in development, in particular, there can be different plausible interpretations of a situation and its causes, as well as what constitutes success or progress, what are appropriate performance targets and how to go about achieving them. Different actors may have their own motives, values or interests and do not necessarily share the same views on a joint undertaking, and there can be barriers to the development of a joint understanding when the various perspectives overlap or even conflict.

Second, we must assess whether our goals or understanding of an issue may change over time, as we learn from implementation and experience gained elsewhere – or have to adapt to changes in context conditions. Are such revisions limited to activities or outputs (deliverables), or do they extend to intermediary outcomes (e.g. when they are considered inappropriate or have negative effects that could not have been foreseen) or even top-level goals? Especially where top-line project goals are not realistically achievable within the prescribed timeframe, programmes must target intermediate changes on the path to a longer term goal. However we may find along the way that this intermediate outcome is not feasible or appropriate for achieving the intended long-term improvement – or that the negative side-effects of working on one element of a complex whole are not foreseeable in advance.

For example, while the aim of building a healthy population has intermediate outcomes that represent unambiguous progress towards the greater goal, an aim such as promoting domestic accountability requires a number of intermediate outcomes that may or may not lead to better accountability. For example, building the capacity of civil society to make demands on government has, in some contexts, led to less accountability where it has resulted in state ‘crack downs’ on dissent, or led to civil society organisations being less responsive to grassroots concerns.

It is important to bear in mind that the source of complexity can be in the situation or in the way the intervention is structured and implemented. There may, for example, be agreement about a problem and what to do about it, as well as considerable certainty that this will solve the problem. But this situation will only remain simple if there is similar agreement within the organisational set-up for implementation. A situation might be simple, but the reality of implementation will be complex if partners cannot commit themselves to tackling this problem, cannot agree on what to do and how, and are uncertain that this will achieve the desired results. In other words, the degree of complexity at play in a given situation has an objective (degree of uncertainty about causal relations) and a subjective dimension (degree of agreement about the challenge and what to do about it).

Why does divergence matter?

Many planning tools attempt to simplify the aims of an intervention in terms of a single ‘bottom line’, or a simple set of indicators and targets that are presumed to provide objective guidance on the progress and success of the initiative. The idea is that setting specific, challenging targets against which implementation can be measured unambiguously will be the best way to lead and motivate action. Also, by focusing on negotiations with partners and interest groups before action, there is an assumption that objectives can be clarified, and an optimum trade-off can be selected.

In the face of complexity, planning processes structured in this way create a culture of reduced collaboration and relationship building, as well as inhibiting learning and acting as a deterrent to creativity and flexibility. Power differentials between actors can lead to imposition. As a result, key processes of collaboration to shape intervention values and set goals are not carried out sufficiently before an intervention begins. There is then no space left for the joint interpretation of information on progress throughout the life of the intervention. Again, this is liable to reduce any sense of ownership of the intervention by project teams as well as partners.

Next part (part 5): Task 3 – Assess the distribution of knowledge and capacities.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity

- Taking responsibility for complexity.

Article source: Hummelbrunner, R. and Jones, H. (2013). A guide for planning and strategy development in the face of complexity. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/publications/583-exploring-science-complexity-ideas-and-implications-development-and-humanitarian-efforts). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: rawpixel on Pixabay, Public Domain.