Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity series (part 9): Move from comprehensive to diversified planning

This article is part 9 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Background Note A guide for planning and strategy development in the face of complexity.

Comprehensive planning leads to voluminous conglomerates of information, which can be very demanding in terms of time and resources as well as difficult to revise. But planning cannot encompass everything and should be selective about purpose and content. And if initial plans should be light and serve primarily as communication tools, they cannot simultaneously respond to all of the different needs of the various actors involved.

First and foremost, a distinction should be made between two planning categories.

- Strategic planning: this deals with the middle or long-term and usually encompasses the whole organisation or intervention. It is based on normative statements about the desired future (the mission or vision), specifies the means to reach it and aims to balance competing demands of the present and the future.

- Operational planning: this deals with short-term issues and might only encompass units responsible for the creation of specific value-added (e.g. deliverables). It is based on provisions made through strategic planning, specifies timing and resource allocation, and aims to ensure coordination and synergies.

In situations where multiple actors located at various levels are expected to collaborate, this distinction can also help to divide planning tasks. In a multilevel planning structure each level should carry out its own operational planning and, at the same time, provide a strategic frame for the level beneath. A clear separation of responsibilities is crucial to make ‘embedded’ plans work: higher levels limit themselves to specifying the framework conditions, but refrain from interfering in micro-management, leaving the details to the lower levels.

There are different approaches to what aspects the higher levels need to fix for the lower levels. It may be, for example, that the higher levels focus on framing an issue and expounding a view on its causes and effects, or it may be that high level planning would best focus on setting boundaries and permissions or minimum standards. But, if done correctly, working with such a ‘hierarchy of plans’ stimulates the self-organisation capacities of each level and improves ownership for development activities. It should also lead to more effective and timely adaptation of plans, with responsibility transferred to those best placed to identify the challenges and opportunities that can be associated with changes in circumstance. Promoting buy-in and ownership throughout the implementation chain or network is of central importance here, as is striking a balance between direction and self-organisation.

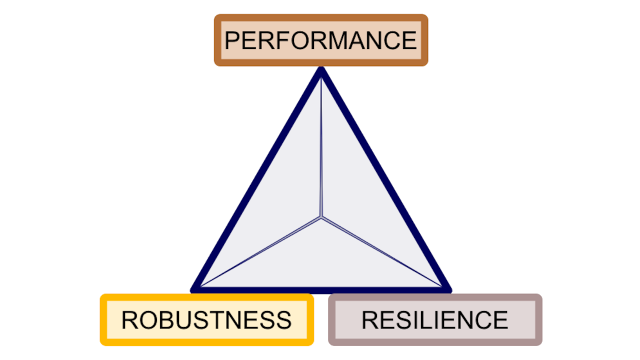

Last but not least, it is recommended that formats should be diversified to make them more user-friendly and appropriate for different target groups. Visual formats, such as logic models, are at the core as they can be updated periodically without great effort and serve as communication tools between the various actors or planning hierarchies. If the programme theory contains complicated and/or complex aspects, the form of representation should allow their capture (e.g. interrelations between multiple components or causal strands, and intended linkages with other interventions or with important contextual factors).

These graphic representations are then specified for different audiences, in line with their respective information needs. For example, an administrative document for the contractual partners can specify the requirements to be met by them (e.g. achievement of milestones, fulfilment of donor requirements, data to be supplied). A guidance document for the actors involved in implementation can explain the strategy and the operations envisaged. Key messages will often have to be conveyed to political decision-makers or the public at large, and while this might not require a ‘document’, it should be part of the communication strategy that should accompany any programme.

Next part (part 10): Appropriate approaches.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity

- Taking responsibility for complexity.

Article source: Hummelbrunner, R. and Jones, H. (2013). A guide for planning and strategy development in the face of complexity. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/publications/583-exploring-science-complexity-ideas-and-implications-development-and-humanitarian-efforts). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: rawpixel on Pixabay, Public Domain.