Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity series (part 10): Appropriate approaches

This article is part 10 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Background Note A guide for planning and strategy development in the face of complexity.

This … [article] outlines specific methods that have been used for planning in the face of complexity. Most of these approaches were developed originally in corporate business, where the shortcomings of static and deterministic planning were first noted, but have since spread into public sector strategy and planning. Each is in line with the principles outlined earlier in this … [series], but has a specific focus and is tailored for particular circumstances or purposes.

Scenario technique

The scenario technique is the classic and most widespread approach. Scenarios are images of the future that help to prepare for the most probable path and to avoid the risks arising from possible but undesirable developments. Against these scenarios, informed judgements can be made to produce decisions and policies that are robust under a variety of circumstances. Scenario development can proceed as follows.

- Define the boundaries of the situation (scenario field) and identify the key factors that will influence success.

- Describe trends and possible development paths for each key factor.

- Analyse their plausibility and cluster them to build coherent scenarios that often encompass three alternatives (e.g. best, worst and probable case).

- Assess the consequences and risks of each and elaborate a strategy that is robust to the plausible scenarios as well as being adaptive to likely opportunities.

Scenario technique is useful for long-term planning in situations where there is significant uncertainty about the future developments for some key variables. It is a reflective (not a predictive) tool that allows the incorporation of multiple perspectives about the future in order to help improve understanding of the dynamics of change, to give clues and signposts about key moments of change and to enable the perception of a wider range of strategic opportunities than might otherwise emerge. Comprehensive scenarios may require substantial time and resources, but there are lighter and highly participatory versions like Future Images or Future Stories.

Conditional planning

In planning we identify individual actions that seem appropriate to achieve objectives and assemble them to form activity chains. But fitting actions together often requires specific conditions, which tend to be neglected in the planning process, as well as during implementation. Planning alternatives or identifying assumptions for an entire intervention (as required in a logical framework) is either too cumbersome or not specific enough to guide decision-making. Conditional Planning links the assumptions and conditions for implementation directly to the actions of a plan. In this approach every activity (chain) consists of three parts:

- activity (what should be done?)

- outcome (what should the activity achieve or contribute to?)

- conditions (which factors should exist to implement the activity successfully?).

Conditions can refer to the outcome of previous activities or contextual factors. They can also express logical connections (‘if, then’) and, therefore, outline options for future decisions. When these conditions are documented during planning, this information is available in the event of changes or unforeseen situations. This also improves transparency and facilitates the transfer of information to actors who were not involved in the planning stage. In general, it is sufficient to specify the conditions only for a few activities that are particularly sensitive or important (e.g. milestones). By planning in this way it is possible to outline the intended pathway to reach objectives, while specifying crucial conditions and retaining possible options.

Conditional planning is best applied when faced with uncertain or dynamic environments. Detailed plans can be made to achieve objectives, but precautions are taken against their mechanistic implementation. This facilitates the review of plans, supports swift decision-making during implementation and finding alternative routes, if necessary. For example, a regional development programme would first identify some key measures, such as establishing a development agency or setting up a development fund. It would then define for each measure the conditions that should be in place in the context (e.g. political support, co-financing, capable project owners) as well as activities that need to be undertaken beforehand (e.g. awareness raising, information campaigns, training).

Milestone planning

An approach related to both the scenario technique and conditional planning is ’milestone planning’, where plans and strategies are elaborated only partially up-front and develop gradually, pivoting around elements of a desired future. Intermediary targets (milestones) are identified that should lead to the desired final state or objective. These milestones are the focus of attention, because they are closer to the present and easier to identify and monitor. Different options to reach a certain milestone can be kept open, and the actual path is determined as late as possible. As with conditional planning, assumptions (and activities) can be associated with each milestone and, therefore, integrated in the plan, which helps to avoid ‘automatic’ implementation of plans without regard for circumstance or the actors involved.

Milestone planning ensures flexibility and, similarly to conditional planning, helps programmes to move ahead even if the final objectives are unclear. This openness is particularly advantageous when dealing with several actors or situations at once, because various alternatives can be pursued while still focussing on joint objectives. This approach uses a sequence of intermediary steps between the present and the future (sometimes labelled a ‘theory of change’). However, in multi-actor settings like a cooperation system, it is best to avoid classifying these elements according to pre-defined categories (e.g. outputs, results and impacts) and to use, instead, a more generic label (e.g. outcomes).

Instead of using linear models, e.g. a result chain, it is more appropriate to use an ‘outcomes hierarchy’ that displays a programme theory as a series of outcomes from beginning to end. This type of representation makes it easier to show how different causal strands are understood to combine (or conflict) in producing the intended outcomes. Activities are not only foreseen at the start (as in a chain), but can be inserted at any stage, integrated in a graph or shown separately (e.g. as a matrix or narrative description). For example, the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) uses such a form of representation in its new impact model.

Assumption-based planning

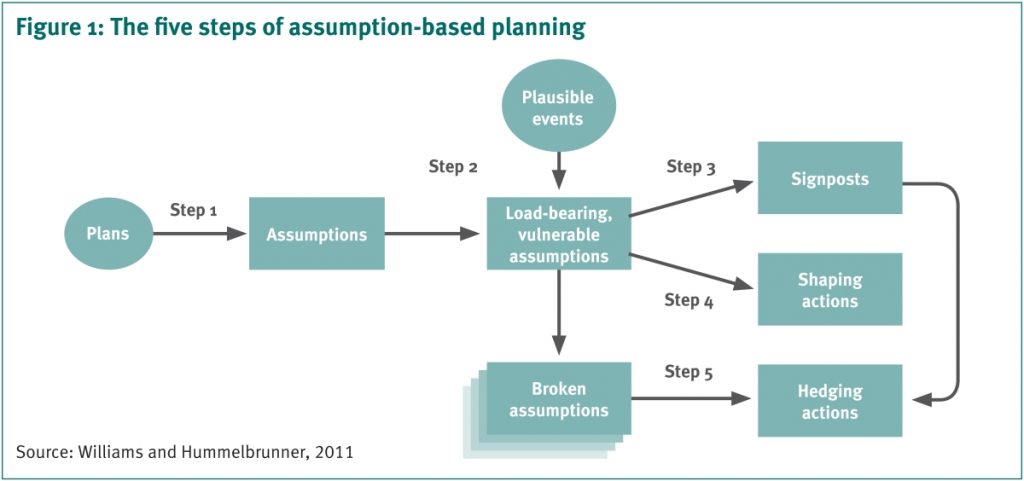

Assumption-based planning (ABP) can be applied if a plan already exists, but is largely incomplete because there are many options and uncertainties. It is based on the experience that plans often fail because inadequate attention is paid to their underlying assumptions about, for example, characteristics of the past, present or future. The emphasis, therefore, is on identifying key assumptions and monitoring them over time to protect the plan from assumption failures. Figure 1 illustrates the five steps of ABP1.

An assumption is load-bearing if its negation would lead to significant changes in the plan and vulnerable assumptions will be invalid if plausible events occur in the environment. Signposts are mechanisms to monitor the uncertainties associated with assumptions and indicate that their status is changing. It is, in other words, becoming vulnerable. A shaping action is designed to take control of the uncertainty and a hedging action helps to cope with the failure of an assumption by, for example, preserving important options by rethinking the plan (e.g. via scenarios).

ABP is effective for mid- and long-range planning in very uncertain times and environments. It generates relevant scenarios systematically and ties actions (‘shaping’ or ‘hedging’) to specific assumptions. Therefore, if the assumption changes, the implications for action are obvious. For example, a long-term programme to mitigate the consequences of climate change could identify as vulnerable all those assumptions that might be affected by a change that might occur within the programme’s time horizon (e.g. flood relief would be affected by severe droughts). A signpost, such as less rainfall, would alert actors that an assumption is going wrong. A shaping action could be to investigate the likely impact of this change on floods and a hedging action would be to reallocate resources to water management instead of building dams.

Boundary planning

The coordination of plans between several partners requires a joint frame of reference, usually consisting of (higher level) objectives. However, there are times when it is neither useful nor possible to define joint objectives – or when they become so vague that they can hardly be operationalised. In this case, boundary planning can be used to provide adequate guidance.

It defines the conditions for successful implementation in negative terms: what needs to be avoided by the partners to achieve objectives (instead of specifying what should be done). This makes it possible to outline the boundaries of (un)desired behaviour or actions, which provides coherence but leaves room for creativity, adaptation and autonomous action.

In order to be effective, the boundary conditions of relevance should consist of a few rules. The specific behaviour or actions will then be decided by the various actors, who apply these rules in a flexible manner within their particular context. Simple rules that are understood by the relevant actors should make it clear when an actor is in or out of bounds. This approach is particularly useful in situations where actors have or need a large degree of autonomy in implementing joint plans. For example, a national programme to combat poverty that takes place in several outlying regions that have little contact with each other would specify situations to be avoided in order to achieve the programme’s aim, such as activities that should not to be considered, social groups to be excluded, and political interference. These then serve as guidelines for the disbursement of the programme funds by the largely autonomous partners.

Adaptive strategy development

In contexts that are changing rapidly and that are unpredictable, success often depends on the ability to detect unanticipated events and make swift use of ‘windows of opportunities’. Adaptive strategy development postulates that strategies should not be designed beforehand but should emerge gradually from individual and loosely connected actions. The starting point is the present (not the future), beginning with an assessment of the effectiveness of current activities and strategies, increasing the sensitivity for change and improving synergies. In addition, past experience should be incorporated to retain elements of past success, such as strengths and skills.

With this approach, not much time is invested in planning. On the basis of a clear vision – a global objective – and some promising leverage points, a series of options is outlined and tested through a variety of actions. Their implementation is observed and the most successful are retained and strengthened. This can include so-called ‘safe-fail experiments’, small actions designed to test ideas to deal with a problem where it is acceptable for them to fail critically, in the interests of the valuable learning gained from a series of low-risk failures. Rapid feedback not only sheds light on how to address a problem, but also captures the unplanned and detects new facts or changes in the environment. In this manner, strategies are grown continually from the change processes initiated simultaneously in several areas.

This form of strategy development is particularly suitable when strategies are uncertain as a result of lack of information or a dynamic environment. Several strategic options can be probed deliberately at the same time and rapid lessons can be learned. The strategic direction unfolds gradually and is in line with the real experience gained as well contextual changes, rather than making large commitments based on insufficient evidence.

Outcome mapping

Outcome mapping is another approach designed for complex problems2. Anchoring planning in an understanding that development interventions have a limited sphere of influence means focusing planning efforts on behaviour changes among the partners with whom the intervention works directly – the ‘boundary partners’. This makes outcome mapping particularly suitable for situations with a higher level of distributed capacities.

Outcome mapping is also designed for situations where change processes involve a high level of uncertainty, providing ways to ensure planning is dynamic and iterative and laying the foundations for continuous learning and flexibility to be built into project management approaches and systems. In addition, the approach rests on ideas similar to our ‘diversified planning’, with exercises designed to be carried out in participation with boundary partners. These partners help to define key behaviour milestones such as ‘outcome challenges’ (ideal behaviour changes in a particular stakeholder group) and ‘progress markers’ (sequential steps of behaviour change leading towards the outcome challenge).

Next part (part 11): Examples of complex planning with logical frameworks.

See also these related series:

- Exploring the science of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity

- Taking responsibility for complexity.

Article source: Hummelbrunner, R. and Jones, H. (2013). A guide for planning and strategy development in the face of complexity. London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/publications/583-exploring-science-complexity-ideas-and-implications-development-and-humanitarian-efforts). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: rawpixel on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References:

- Williams, R. and Hummelbrunner, R. (2011). Systems Concepts in Action: A practitioners toolkit. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ↩

- Earl, S., Carden, F. and Smutylo, T. (2001). Outcome Mapping: Building Learning and Reflection into Development Programs. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre. ↩