Exploring the science of complexity series (part 11): Concept 2 – Feedback processes promote and inhibit change within systems

This article is part 11 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts.

Complexity and systems – Concepts 1, 2, and 3

Complexity sciences look at the phenomena that arise in systems of interconnected and interdependent elements and multiple dimensions (Concept 1). Both positive and negative feedback processes take place (Concept 2), acting to dampen or amplify change; emergent properties (Concept 3) result from the interactions of the elements, but these are not properties of the individual elements themselves.

These first three concepts help to clarify aspects of systems that are complex, drawing on applications from social, economic and political life. These are features by which complexity in a given system can be recognised.

Concept 2 – Feedback processes promote and inhibit change within systems

… feedbacks are central to the way systems behave. A change in an element or relationship often alters others, which in turn affect the original one1

Outline of the concept

Feedback, as illustrated in the quote above, is at the heart of phrases such as ‘vicious circles’ or ‘selffulfilling prophecies’ and, in this broad sense, can be described as an influence or message that conveys information about the outcome of a process or activity back to its source2. At its most basic, feedback can be amplifying, or positive, such that a change in a particular direction or of a particular kind leads to reinforcing pressures which lead to escalating change in the system3 4. Feedback can also be damping, or negative, such that the change triggers forces that counteract the initial change and return the system to the starting position, thereby tending to decrease deviation in the system.

Although feedback plays out in very distinctive ways in complex systems, the basic principles are the same as in simpler systems. The major differences relate to how feedback is treated – in simpler systems, feedback may be linear, predictable and consistent. In complex systems, as Byrne suggests5, feedback is about the consequences of nonlinear, random change over time.

Detailed explanation

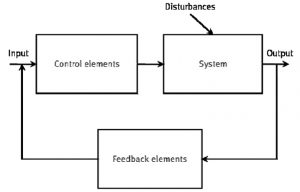

In simple systems, the dynamics and information flows around the system are referred to as feedback loops. This is usually represented mechanically, as shown in the typical example of a feedback system in Figure 1 below. Input into a system results in an output which feeds back into the system again, potentially adjusting the inputs.

Although feedback in complex systems is distinct from that in more simple systems, the basic principles are the same. Simply put, feedback can be amplifying, or positive, such that a change in a particular direction or of a particular kind leads to reinforcing pressures which lead to escalating change in the system8 9. Feedback can also be damping, or negative, such that the change triggers forces that counteract the initial change and return the system to the starting position, thereby tending to decrease deviation in the system. Negative feedback is associated with the concept of homeostasis, which will be addressed in Concept 10.

Mittleton-Kelly10 provides a useful qualification by suggesting that it is feedback processes, rather than feedback loops, that are to be found in complex systems. For example, like any complex system, the Earth’s climate has many feedback processes. Some of these amplify and reinforce an underlying trend and so destabilise the climate, moving it in new directions. Other feedbacks are fundamentally stabilising, in that they counteract the original change and return the climate to equilibrium. Scientists do not understand many of the principal feedbacks in the Earth’s climate but are most concerned with the positive feedback that could drive climate to a higher temperature or even produce a runaway greenhouse effect. Events in the Arctic show how this could happen – open water left by the Arctic ice melting is much darker and absorbs about 80% more solar energy than ice, which makes the waters warmer, melting ice and leading to more ‘dark’ water – this could change the energy balance of the entire Northern hemisphere. Simultaneously, northern boreal forests will die as the Arctic warms, releasing more carbon into the atmosphere. And the 2,500 cubic kilometres of peat under the tundra of Siberia, Alaska and Canada would release vast amounts of methane into the atmosphere. Climate scientists have also identified some counterbalancing negative feedback processes – the newly melted Arctic may absorb more carbon dioxide. There is fierce debate about the relative influence of positive and negative feedbacks, but in recent years the evidence is mounting that dangerous positive feedbacks are outweighing negative ones11.

Work on the international food system has highlighted that feedback may also be masked or disregarded12. Because of the distances between the use of resources and the environmental consequences – both in times of geography and time – feedback signals are not perceived or are difficult to correlate to consumer choices and management practices. Such feedback might occur at a scale where the information cannot be detected or transferred – masked feedback – or is not acted upon despite the fact that it is perceived (disregarded feedback). Feedback relationships that are not functioning properly can have serious implications for the food system and life-supporting ecosystems. While unmasking masked feedback is often a question of deepening the understanding of ecosystem functioning through scale-relevant monitoring and institutions, coping with disregarded feedback is a matter of enhanced communication between actors in the food system.

In simple systems, feedback operates in a relatively straightforward and predictable fashion. In complex systems, by contrast, feedback processes occur when there is change among any of the elements or dimensions of a system, which then have a dynamic influence on other elements or dimensions. This has clear relationships with the degree of connectivity of the system, as outlined in Concept 1. Meadows takes the bath tub metaphor mentioned earlier and skilfully uses it to illustrate feedback in complex systems:

… mentally turn the bath tub into a [bank] account. Write checks, make deposits, add a faucet that keeps dribbling in a little interest …

This creates a simple predictable system of stocks and flows. Meadows continues:

… attach your bank account to thousands of others and let the bank create loans as a result of your combined and fluctuating deposits. Link a thousand of those banks into a federal reserve system … Simple, predictable stocks and flows, plumbed together, make up a system [that is] complex13

In such a system, changes in the elements and dimensions mutually feed back to each other in a continually dynamic manner14. Any change in a particular element or dimension has an influence on others in the system, causing further changes around the system15. In more complex systems, several interacting feedback processes mean that changes in some directions are amplified while changes in other directions are suppressed (other distinctions made between complexity science and systems thinking, some of which were outlined in Box 1 … [in part 7 of this series]).

The word ‘tends’ is often used in the context of feedback processes in complex systems, as other factors may also influence the change or deviation. A rather more prosaic example than the previous one on global climate change can be drawn from the situation of facilitating meetings. Consider a situation where a particular topic is under discussion, and a particular participant suggests broadening the conversation to cover other areas. Such a deviation may tend to make the discussion facilitator steer the discussion back to the original topic, which returns the overall discussion to the planned agenda. Fellow participants may wish to go in the new direction suggested, or the facilitator may not feel confident to speak against the suggestion, both of which would work against the tendency.16

This can lead to very complicated and difficult-to-predict behaviour17. Work by IDRC on the ecosystem approach highlights some of the broader implications of these issues in social settings:18

An enforced policy on low-pollution transportation could within a few years result in cleaner air, less respiratory disease, healthier people who walk more – as well as the loss of income from motor-related activities and a change in the physical structure of the cities and in structure of the national economy. Building a road may increase access of poor villagers to markets (increasing income), but also result in restructuring of the landscape and the local economy in ways that ultimately drive the farmers from the land. The exact outcome cannot be predicted19

Example: UK political debates and feedback

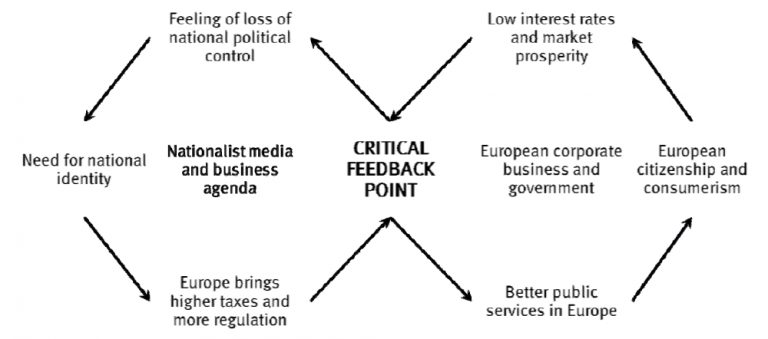

UK political engagement with the complex factors behind the EU illustrates aspects of feedback in public debates20. In the build-up to the 2001 election, the New Labour agenda was to create positive feedback around the Euro issue leading to change, whereas the more sceptical Conservative party attempted to reinforce negative feedback, inhibiting change. Specifically, a number of key variables were identified by both sides, and the relationship between them was highlighted in order to support their separate arguments (see Figure 2).

At the same time as trying to maintain their preferred set of relationships in the minds of the public, the parties had to deal with wider issues such as the movement of the Euro on currency markets and public reactions in other countries. Figure 2 illustrates how the debate on the Conservative side created a set of assumptions that were geared towards minimising change (the left-hand side of the figure), whereas New Labour was working towards amplifying change (the right-hand side).

Implication: Identify and work with the positive, negative, masked and disregarded feedback processes that foster and inhibit change

In order to better understand how feedback plays out in the international aid system, it is important to pay careful attention to areas where change has not happened despite continual pressure, and to areas where there has been considerable change. It is useful to assess how negative and positive feedback plays out over time in the context of the relationships embedded in the international development system between the various communities, institutions, countries, etc. There is also feedback that plays out between different dimensions of the development, and between different dimensions and specific elements.

Incorporating feedback can have dramatic effects on models of complex systems. For example, the Stern Review highlights that the cost of climate change over the next two centuries will be equivalent to a loss of at least 5% of global per capita consumption in perpetuity. However, scientific evidence has highlighted a number of important feedback loops, whereby rising temperatures could lead to further increases in greenhouse gases through the release of carbon dioxide from soils and methane from permafrost, thereby boosting the global temperature response to greenhouse gas emissions. When Stern’s analysis incorporates these known feedback loops, the total average cost rises from 5% to 14.4% of global per capita consumption22. In complex systems, positive feedback can make deviations grow in a runaway, explosive manner, leading to accelerating changes and potentially a radically different configuration for the system23.

The notion of feedback can help to better understand an increasing range of phenomena being faced by international agencies. For example, beyond its economic effects, climate change is also seen as contributing to the rise in disasters. Much of this thinking suggests that disasters are discrete phenomena that are external to the social or environmental systems upon which they impinge. According to this approach, disasters and society are related to one another in a linear, cause and effect manner. However, in reality, growing population, migration of population to coasts and to cities, increased economic and technological interdependence, and increased environmental degradation are just a few of the factors that feedback into each other and underlie the increase in disasters24 25. Feedback suggests that there is a different way to view disasters: not as isolated phenomena, but as the result of escalating positive feedback within or between complex, dynamic systems.

Consider the following three ingredients: a mega-city in a poor, Pacific rim nation; seasonal monsoon rains; a huge garbage dump. Mix these ingredients in the following way: move impoverished people to the dump, where they build shanty towns and scavenge for a living in the mountain of garbage; saturate the dump with changing monsoon rain patterns; collapse the weakened slopes of garbage and send debris flows to inundate the shanty towns. That particular disaster, which took place outside of Manila in July 2000, and in which over 200 people died … starkly illustrates the central point that disasters are characterised and created by context. The disaster was not inherent in any of the three ingredients of that tragedy; it emerged from their interaction26

In many parts of any economy, there are positive feedback processes at play, which magnify the effect of small economic shifts. Once economic forces select a particular path, they may become locked in, regardless of the advantages of other paths. If one product or nation in a competitive marketplace gets ahead, it tends to stay ahead and even increase its lead. This concept, known to economists as path dependence, will be explored in more depth later, in Concept 5. By contrast, Arthur’s work27 on feedback and economics argues that conventional economic theory – with its focus on diminishing returns – overemphasises negative feedback. Specifically, economic actions eventually lead to negative feedback loops which, in turn, lead to a predictable equilibrium for prices and market shares. According to conventional theory, the equilibrium marks the ‘best’ outcome possible under the circumstances: the most efficient use and allocation of resources. Negative feedback in this sense tends to stabilise the economy, because any major changes will be offset by the very reactions they generate.

In order to illustrate the implications of positive and negative feedback in the aid world, it is worth drawing on the work of a leading analyst [Killick]28 who suggests that there have been major movements in almost all dimensions of British aid policies to Africa in the past four decades. To cite a few examples, the department responsible has shrunk and grown, there have been changes in the influence of commercial motives, there have been changes in the real value of aid, there have been changes owing to lessons learned, there have been changes away from growth towards poverty reduction, and so on. Importantly, Killick also suggests that it is ‘almost inevitable’ that changes at ground level have been less dramatic than those at head office and policy levels.

Applying the concept of feedback would imply that the feedback processes at the head office and policy level are more likely to be amplifying and more change-enabling than those surrounding the work of agencies in developing countries, where there may be some degree of homeostasis and where negative feedback processes that inhibit change may prevail. Moreover, the international aid system may be characterised by both masked and disregarded feedback. The sheer size and scope of the system, and the loose coupling that occurs between the different elements, may mask many aspects of the system. Furthermore, the political dimensions within which aid is embedded may also lead to disregarding feedback as to the actual effects of aid.

An approach for furthering such understanding, Drivers of Change, has been developed within DFID29. This approach was motivated by the fact that donor organisations frequently explained away the failure of their programmes by pointing to a lack of political will for change among aid recipients, without examining the underlying reasons for this lack of the will. Drivers of Change was developed as a learning exercise to enable a better appreciation of the interlocking causes that make progressive change so difficult in some of the poorest developing countries. This includes assessments of the ways in which the efforts of donor organisations can become part of the problem rather than a source of solutions. The exercise enables an approach to aid policy that focuses on how the complex interaction between economic, social and political factors can variously enable and inhibit change.

The above suggests there needs to be more attention within development agencies to how strategies for change address broader dynamics of feedback, positive and negative. Of particular importance is the fact that feedback processes do not always produce the same effects and are not predictable. In addition, because such complex feedback loops have both positive and negative effects, different people will look at the same situation and evaluate it differently. Where one sees the excitement of economic activity, another sees deforestation; where one sees disease control by draining swamps, another sees loss of wildlife and clean water provided by the filtering effects of wetlands; where one sees more robust housing provision through metal roofing, another sees increased costs and less comfortable houses. As such, international aid should be seen as part of broader, often unpredictable, processes of feedback, which play out differently at local levels. An ODI study summarises these issues succinctly in the context of the dependency of disaster-affected populations on humanitarian relief:

Rather than seeing dependency on relief as necessarily negative, we should be trying to understand the role that relief plays in the complex web of interdependencies that make up livelihoods under stress in crises. The many interdependencies that comprise a community’s social relations and people’s livelihoods may have both positive and negative aspects … external aid influences these existing patterns of social relations and, if it continues over a prolonged period, it may become embedded within them30

Next part (part 12): Concept 3 – System characteristics and behaviours emerge from simple rules of

interaction.

Article source: Ramalingam, B., Jones, H., Reba, T., & Young, J. (2008). Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts (Vol. 285). London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/publications/583-exploring-science-complexity-ideas-and-implications-development-and-humanitarian-efforts). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: qimono on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References and notes:

- Jervis, R. (1997). System Effects: Complexity in Political and Social Life, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ↩

- Capra, F. (1996). The Web of Life, London: Flamingo/Harper Collins. ↩

- Jervis, R. (1997). System Effects: Complexity in Political and Social Life, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ↩

- Maruyama, M. (1968). ‘The Second Cybernetics: Deviation Amplifying Mutual Causal Processes’ in Buckley, W. Modern Systems Research for the Behavioural Scientist, Chicago: Aldine. ↩

- Byrne, D. (1998). Complexity Theory and the Social Sciences: An Introduction, London: Routledge. ↩

- Schueler, G.J. and Schueler, B.J. (2001). ‘Feedback Loops’, Part 10 of ‘The Chaos of Jung’s Psyche’. ↩

- Meadows, D. (1999). ‘Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System’, Whole Earth, Winter 97. ↩

- Jervis, R. (1997). System Effects: Complexity in Political and Social Life, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ↩

- Maruyama, M. (1968). ‘The Second Cybernetics: Deviation Amplifying Mutual Causal Processes’ in Buckley, W. Modern Systems Research for the Behavioural Scientist, Chicago: Aldine. ↩

- Mittleton-Kelly, E. (2003). ‘Ten Principles of Complexity and Enabling Infrastructures’ in Complex Systems and Evolutionary Perspectives of Organisations: The Application of Complexity Theory to organizations, London: Elsevier Press. ↩

- Homer-Dixon, T (2005). The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity and the Renewal of Civilisation, Bodmin: Souvenir Press. ↩

- Sundkvist, A., Milestad, R. and Jansson, A. (2005). ‘On the Importance of Tightening Feedback Loops for Sustainable Development of Food Systems’, Food Policy 30, 224–39. ↩

- Meadows, D. (1999). ‘Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System’, Whole Earth, Winter 97. ↩

- Haynes, P. (2003). Managing Complexity in the Public Services, Berkshire: Open University Press. ↩

- Capra, F. (1996). The Web of Life, London: Flamingo/Harper Collins. ↩

- For more on how complexity can be applied to facilitation, see Robert Chambers on self-organising systems on the edge of chaos (SOSOTEC); Chambers, R. (1997). Whose Reality Counts: Putting the First Last, London: Intermediate Technology Publications. ↩

- Heylighen, F. (2001) ‘The Science of Self-organization and Adaptivity’, Center Leo Apostel, Free University of Brussels, Belgium. ↩

- The ecosystem approach is perhaps the area of aid work which has seen the greatest and most systematic application of complexity science. See the journal of the International Society of Ecological Economics for more details: www.isecoeco.org ↩

- Waltner-Toews, D. (1999). An Ecosystem Approach to Health: Communicable and Emerging Diseases, Document presented in the seminar An Ecosystem Approach to Human Health: Communicable and Emerging Diseases. Río de Janeiro-Brazil, 7–12 November 1999. ↩

- Haynes, P. (2003). Managing Complexity in the Public Services, Berkshire: Open University Press. ↩

- Haynes, P. (2003). Managing Complexity in the Public Services, Berkshire: Open University Press. ↩

- HM Treasury (2006). The Stern Review of the Economics of Climate Change, London: HM Treasury. ↩

- Heylighen, F. (2001) ‘The Science of Self-organization and Adaptivity’, Center Leo Apostel, Free University of Brussels, Belgium. ↩

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (1999). World Disaster Report, Geneva: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. ↩

- CRED (2001). Center for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 2001. ↩

- Sarewitz, D. and Pielke, R. (2001). ‘Extreme Events: A Research and Policy Framework for Disasters in Context’. ↩

- Arthur, W.B (1990). ‘Positive Feedbacks in the Economy’, Scientific American 262 (February): 92–9. ↩

- Killick, T. (2005). ‘Policy Autonomy and the History of British Aid to Africa’, Development Policy Review 23(6): 665–81. ↩

- Booth, D., Cammack, D., Harrigan, J., Kanyongolo, E., Mataure, M. and Ngwira, N. (2006). Drivers of Change and Development in Malawi, Working Paper 261, London: ODI. ↩

- Harvey, P. and Lind, J. (2005). Dependency and Humanitarian Relief: A Critical Analysis, HPG Research Briefing 19, London: ODI. ↩