Exploring the science of complexity series (part 12): Concept 3 – System characteristics and behaviours emerge from simple rules of interaction

This article is part 12 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts.

Complexity and systems – Concepts 1, 2, and 3

Complexity sciences look at the phenomena that arise in systems of interconnected and interdependent elements and multiple dimensions (Concept 1). Both positive and negative feedback processes take place (Concept 2), acting to dampen or amplify change; emergent properties (Concept 3) result from the interactions of the elements, but these are not properties of the individual elements themselves.

These first three concepts help to clarify aspects of systems that are complex, drawing on applications from social, economic and political life. These are features by which complexity in a given system can be recognised.

Concept 3 – System characteristics and behaviours emerge from simple rules of interaction

… From the interaction of the individual components … emerges some kind of property … something you couldn’t have predicted from what you know of the component parts … And the global property, emergent behaviour, feeds back to influence the behaviours of the individuals that produced it1

Outline of the concept

At its simplest, emergence describes how:

… a [complex] system emerges from the interactions of individual units … The units … are driven by local rules… and are not globally coordinated2

Emergent properties are often used to distinguish complex systems from applications that are merely complicated. They can be thought of as unexpected behaviours that stem from basic rules which govern the interaction between the elements of a system.

Detailed explanation

Many patterns and properties of a complex system emerge from the interrelations and interaction of component parts or elements of the system. These can be difficult to predict or understand by separately analysing various ‘causes’ and ‘effects’, or by looking just at the behaviour of the system’s component parts. They are known as emergent properties, and they form an important element in the defining concepts of complex systems. This concept of emergent properties is far from being a new one in social, economic and political thinking. As one writer has it:

It has been held that order in market systems is spontaneous or emergent: it is the result of “human action and not the execution of human design”. This early observation, well known also from the Adam Smith metaphor of the invisible hand, premises a disjunction between system wide outcomes and the design capabilities of individuals at a micro level and the distinct absence of an external organizing force3

Work at the University of Strathclyde has established that structure, processes, functions, memory, measurement, creativity, novelty and meaning can all be identified as emergent properties in complex systems. The researchers involved have used this to develop a useful classification of the kinds of emergence that occur in complex systems4. Emergence describes how overall properties of a complex system emerge from interconnections and interaction. While the nature of the entities, interactions and environment of a system are key contributors to emergence, there is no simple relationship between them. Emergence has been used to describe features such as social structure, human personalities, the internet, consciousness and even life itself. As one lucid account has it5:

…metaphors [are] useful. The music created by an orchestra may be envisaged as an emergent phenomenon that is a result of the dynamic, temporal interactions of many musicians at a point in time… the process that is the music may alter a listeners actions or behaviours in the real world… this viewpoint supports the proposition that complex systems, such as people, have multiple emergent levels, each level generating phenomena that is more that the sum of the parts and is not reducible to the parts…

Emergence, then, describes how a system emerges from the interactions of individual units driven by local rules6. The dynamic feedback between the parts crucially shapes and changes the whole7. One of the most widely cited examples of computerised emergence is the boids application, developed by Craig Reynolds8. This visual tool shows how models of flocking birds can be created by programming visuals on a screen using three basic rules: separation of flight path from that of local boids, alignment of steering with the average direction of the local flock, and cohesion to move towards the average position of the local flock. Perhaps the best known example of organisational emergence is that which is promoted within US marine operations which, like the boids, have a set of three rules that govern military behaviour in complex and unpredictable environments. These are: 1) capture the high ground; 2) stay in touch; and 3) keep moving. This enables maximum adaptive behaviours in the context of operational work. It is also worth noting that the internet embodies emergent properties on a grand scale. As Plant puts it:

… no central hub or command structure has constructed it … It has installed none of the hardware on which it works, simply hitching a largely free ride on existing computers, networks, switching systems, telephone lines … [it] presents itself as a multiplicitous, bottom-up, piecemeal, selforganising network which could be seen to be emerging without any centralized control9

But you do not have to look to the computer world to find examples of emergence. Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ is perhaps the best known and most frequently cited example of emergent properties, as seen above, and is at the heart of economic thinking. Similarly, the alternative globalisation movement that has arisen in global civil society has the ‘emergent properties of acting in a decentralised, participatory, and highly democratic manner’ 10. As with the web, this is the product of interactions among various parts of civil society, and is not implemented as part of some overall ‘plan’.

Overall, the principles of emergence mean that over-controlling approaches will not work well within complex systems – that in order to maximise system adaptiveness, there must be space for innovation and novelty to occur. While this may be obvious, this is often the reverse of what happens in the real world, because of a tendency to over-define and over-control rather than simply focus on the critical rules that need to be specified and followed11.

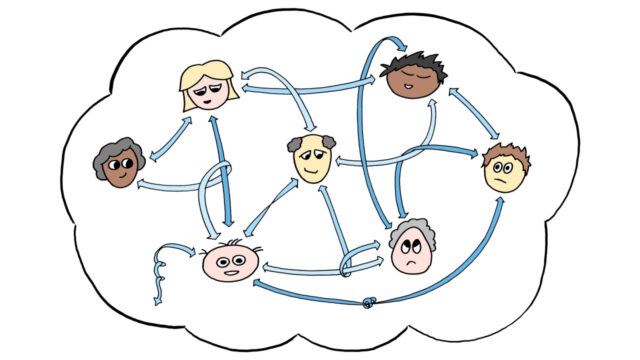

Example: public sector accountability as an emergent property of a complex system

Work by researchers at the University of Kentucky12 uses the term ‘accountability environment’ to capture the emergent nature of accountability in public sector organisations. In this approach (consistent with a school of thinking termed new institutionalism), public sector organisations are shaped and structured by interactions between themselves and other entities in their organisational ‘field’. Besides the focal organisation, the field includes the external organisations and social groups that make up the organisation’s stakeholders. The constituent parties in a field might include competitors, suppliers, unions, environmentalists, local residents, government regulators, local contractors, customers / clients, with internal management being just one of a number of parties.

Similarly, managers of aid organisations operate in a field that comprises other parties – that is, a program field. Each party in the field can hold the organisation accountable for some particular output. The overall accountability environment is the ‘constellation of forces – legal, political, socio-cultural, and economic – that place pressure on organisations and the people who work in them to engage in certain activities and refrain from engaging in others’ 13. Different parties can press for accountability for different concerns. In particular, there are three dimensions of accountability which are of relevance: finances, performance and fairness. A donor might expect an implementing agency to provide a high quality of service (performance) at a lower cost (finance) while serving more citizens in a more equitable manner (fairness).

With these multiple concerns and multiple actors, accountability can be seen as the ‘multidimensional product of many forces operating in the accountability environment’. The overall level of accountability – while measurable at times – is not a predictable product of hierarchical relationships and managerial rules. Rather, with multiple actors who have a variety of ties to each other and differing goals, the degree and nature of accountability is best described as an emergent property which is a result of the interactions between actors. By implication, to enlarge total accountability, it is necessary to attend to the web of relationships between the parties and to the resources they bring to the setting. That accountability is the emergent result of complex interactions between multiple actors is to be expected. ‘[I]n today’s world no single person, group or organisation has the power to resolve any major public problem; yet at the same time, many people, groups and organisations have a partial responsibility to act on such problems’ 14. It is for this reason that accountability can be seen as an emergent property, and as more than a collection of rules and procedures.

Implication: Approach ‘grand designs’ with care

Chambers argues in Whose Reality Counts? that top-down attempts to manage complex interrelations have not worked in development aid – such efforts have generated ‘dependency, resentment, high costs, low morale and actions which cannot be sustained’ 15. The applicability of the emergence concept is seen as having some potential, although it is qualified it as follows:

… development projects can be paralysed by overloads at their centres of control. But they differ from [computer simulations]. Projects deal with varied environments and idiosyncratic people as independent agents. The simple rules which then work have to go further, allowing and enabling people to manage in many ways with their local, complex, diverse, dynamic and unpredictable conditions, and facilitating not the uniform behaviour of flocks but the diverse behaviour of individuals

Examples are provided of a southern Indian NGO that runs savings and credit societies, using only two minimal rules: 1) there is transparent, accurate and honest accounting; and 2) those with special responsibility are democratically elected, regularly rotated and not given honorifics, but called ‘representatives’. As Chambers suggests:

… the key is to minimise central controls, and to pick just those few rules which promote or permit complex, diverse and locally fitting behaviour

In fact, looking at the development world, there are some interesting examples of minimum rules used to promote certain kinds of initiatives. For example, the well publicised example of Uganda’s 1990s HIV/AIDS campaign16, referred to by some as a miracle, is synonymous with the ABC approach to HIV/AIDS prevention. ABC stands for ‘Abstain, Be faithful, use Condoms’, and refers to the necessary changes in individual behaviours, as well as the programmatic tools and techniques designed to promote these behaviours.

The evidence shows that some combination of important changes in all three of these sexual behaviours contributed both to Uganda’s extraordinary reduction in HIV/AIDS rates and to the country’s ability to maintain its reduced rates through the second half of the 1990s. This drastic reduction can be seen an emergent property of implementing the three ‘minimum rules’. Subsequently, Western leaders backing the export of the ABC approach elsewhere in Africa, with rather less success (for example in Botswana). A vigorous debate in ongoing around the widespread applicability of this approach to other countries.

This debate highlights an important aspect of dealing with emergence. It may be easy to say that those working in aid organisations who are in the position to determine programmes and projects should define no more than is absolutely necessary to launch a particular initiative, and that the role of grand designer should be avoided in favour of the role of facilitation, orchestration and creating the enabling environment that allows the system to find its own form17. However, in specifying the minimum rules, it is crucial to understand the dynamics of local circumstances and actors. As Holland puts it:

… [emergent properties are global, but] context … determines their function. It is important to build a perspective on an issue from the point of view of those who live their lives immersed in it18

This heightens the importance of local knowledge and a good understanding of the contexts in which an agent is acting within a complex system. One needs a detailed understanding of the factors and dimensions of the complex social system that affect an area in order to refine one’s perspective to see which features are important and which are irrelevant to the context. One must then look to discern the wider patterns that drive these factors. It is quite possible that

… rules governing [the local context are likely to be] only be partially and inadequately understood by the outside actor19

The case for seeking out, transferring and harnessing knowledge of local actors increases in importance from the perspective of emergent properties. More generally, the changing demographic, economic and environmental conditions around the world are the dynamic contexts within which aid problems will emerge, be experienced and have to be addressed. This, in combination with the point about local actors, gives a sound theoretical basis for the argument made in the Tsunami Joint Evaluation, the first recommendation of which was to reorient the international aid system towards local actors and affected peoples.

Next part (part 13): Concept 4 – Nonlinearity.

Article source: Ramalingam, B., Jones, H., Reba, T., & Young, J. (2008). Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts (Vol. 285). London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/publications/583-exploring-science-complexity-ideas-and-implications-development-and-humanitarian-efforts). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: qimono on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References:

- Langton, cited in Urry, J. (2003). Global Complexity, Cambridge: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ↩

- Marion, R. (1999). The Edge of Organization: Chaos and Complexity Theories of Formal Social Systems, Sage: Thousand Oaks. ↩

- Markose, S. (2004). ‘Introduction to Markets as Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) and Agent-based Modelling’. ↩

- McDonald, D. and Weir, G.R.S. (2006). ‘Developing a Conceptual Model for Exploring Emergence’, Computer and Information Sciences, University of Strathclyde. ↩

- Newell, D (2003). ‘Concepts in the study of complexity and their possible relation to chiropractic healthcare’ in Clinical Chiropractic (2003) 6, 15-33. ↩

- Marion, R. (1999). The Edge of Organization: Chaos and Complexity Theories of Formal Social Systems, Sage: Thousand Oaks. ↩

- Haynes, P. (2003). Managing Complexity in the Public Services, Berkshire: Open University Press. ↩

- Cited in Chambers, R. (1997). Whose Reality Counts: Putting the First Last, London: Intermediate Technology Publications. ↩

- Plant, cited in Urry, J. (2003). Global Complexity, Cambridge: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. ↩

- Chesters, G. (2004). ‘Global Complexity and Global Civil Society’, Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 15. ↩

- Morgan, G. (1986). Images of Organization, 3rd edition updated in 2006 London: Sage. ↩

- O’Connell, L (2005). ‘Program Accountability as an Emergent Property: The Role of Stakeholders in a Program’s Field’ Public Administration Review, January/February 2005, Vol. 65, No. 1. ↩

- O’Connell, L (2005). ‘Program Accountability as an Emergent Property: The Role of Stakeholders in a Program’s Field’ Public Administration Review, January/February 2005, Vol. 65, No. 1, p. 86. ↩

- O’Connell, L (2005). ‘Program Accountability as an Emergent Property: The Role of Stakeholders in a Program’s Field’ Public Administration Review, January/February 2005, Vol. 65, No. 1, p. 86. ↩

- Chambers, R. (1997). Whose Reality Counts: Putting the First Last, London: Intermediate Technology Publications. ↩

- Cohen, S. (2003). ‘Beyond Slogans: Lessons From Uganda’s Experience With ABC and HIV/AIDS’, The Guttmacher Report on Public Policy 6(5). ↩

- Morgan, G. (1986). Images of Organization, 3rd edition updated in 2006 London: Sage. ↩

- Holland, J. (2000) Emergence: From Chaos to Order, Oxford: OUP. ↩

- Holland, J. (2000) Emergence: From Chaos to Order, Oxford: OUP. ↩