Exploring the science of complexity series (part 27): Concluding remarks – Our View: Champions, pragmatists or critics?

This article is part 27 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts.

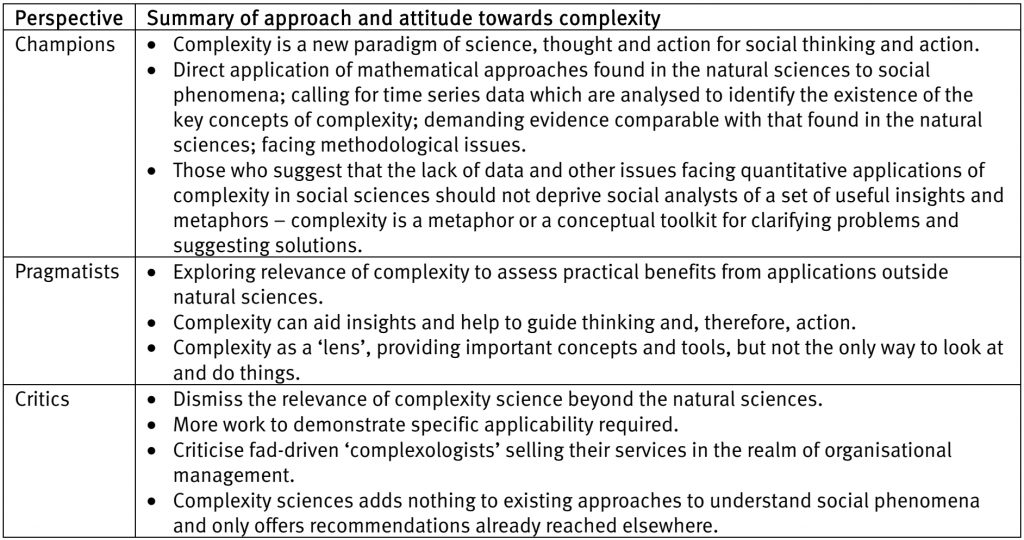

There are a number of problems and pitfalls facing the application of complexity to public sector efforts, specifically within the international aid sector. These are not insurmountable. It is worth revisiting the three contrasting perspectives outlined in … [part 8], presented in Figure 1 below.

We have tried to be keenly aware of these different approaches and not to overextend the potential applications of complexity. This requires careful and considered application of the concepts of complexity to international aid. While this may limit the immediate applicability of complexity, it does not detract from its potential power. Importantly, a growing number of applications have tried to take serious account of the (sometimes strident) objections that have been made to the application of complexity to socioeconomic phenomena. While our reference to the original science has made us highly sensitive to the careless application of all of these concepts to social sciences, enough serious thinkers are engaging with these issues to give cause for comfort.

However, if in attempting to use the principles of complexity science in international development and humanitarian efforts it is found that certain aspects of a particular phenomenon can be appropriately characterised using a complexity concept, this does not mean that this aspect is in some way the most important feature, or that increasing awareness of this factor is automatically a valuable or useful thing. The fact that complexity can offer new ways of looking at aspects of development problems and a focus on different sorts of features and processes in no way suggests that these features will be the crucial aspect of some problem. For example, the concept of a complex system shows that there are new possibilities regarding the way that things behave and change over time. This does not mean that any one particular phenomenon is best explained using the concepts of complexity. Some writers appear disinclined to address the issue of whether it is appropriate to apply a concept to a situation. Where this occurs, the reading at best is that their reference to complexity is as a metaphor, thereby at most suggesting interesting potential relationships between factors and elements being described.

Building on the previous issue, if some phenomena can be properly characterised and described using complexity science, and are seen to be crucial features of a situation, this does not necessarily mean that a particular action should automatically follow. Theoretical understanding of complexity is at an early stage and, from some perspectives, there may not appear to be a great deal of prescriptive power within the key concepts. This issue is frequently come across. For example, some writers use complexity to advocate endlessly increasing actors’ connections with each other, or to suggest that allowing self-organisation will unquestionably lead to better results or that organisational strategy is best left as something that ‘emerges’, i.e., is unplanned.

Our examination of complexity science and its underlying principles suggests that these kinds of recommendations do not naturally follow from the concepts of complexity. Perhaps the greatest challenge in using and applying complexity concepts to development and humanitarian issues systems stems from the fact that they fundamentally state that the best course of action will be highly context-dependent.

In our view, the value of complexity concepts are at a meta-level, in that they suggest new ways to think about problems and new questions that should be posed and answered, rather than specific concrete steps that should be taken as a result. This means that they may be more useful in addressing questions of ‘how’ international aid work should be undertaken. The potential value and relevance of this is outlined in the following quote, taken from a recent large scale evaluation of relief efforts:

…International agencies need to pay as much attention to how they do things, and their capacities to do them, as they do to the content of their policies and programmes… sensitivity to context and the flexibility to adapt to evolving realities are essential, instead of applying predetermined strategies and one-size-fits-all solutions… (emphasis added)1

This highlights the most important implication of complexity science – that it provides ways for practitioners, policy makers, leaders, managers, researchers, [to] all stop and collectively reflect on how we are thinking about trying to solve aid problems. Are we using inappropriate mental models and frameworks? Are we continuing to act in inflexible, top-down ways? Are we using too many off-the-peg approaches? Are we driven by naïve expectations of impact? Do we simplify complexities for the sake of convenience?

These questions – many of which will be familiar – are challenging, highly necessary, and can be sharpened and honed using the ideas of complexity science.

Next (final) part (part 28): Concluding remarks – The challenge of applying complexity science to development and humanitarian work.

Article source: Ramalingam, B., Jones, H., Reba, T., & Young, J. (2008). Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts (Vol. 285). London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/publications/583-exploring-science-complexity-ideas-and-implications-development-and-humanitarian-efforts). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: qimono on Pixabay, Public Domain.

Reference:

- Telford, J. and Cosgrove, J. (2006). Joint Evaluation of the International Response to the Indian Ocean Tsunami: Synthesis Report, Tsunami Evaluation Coalition. ↩