Exploring the science of complexity series (part 28): Concluding remarks – The challenge of applying complexity science to development and humanitarian work

This article is part 28 of a series of articles featuring the ODI Working Paper Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts.

Based on our exploration, we feel safe in saying that development is a complex adaptive process – it is highly local, particular, context-bound, time-specific, path-dependent, etc. Similarly, immediate responses to humanitarian crises are local, complex and adaptive – in the Asian tsunami, 97% of lives that were there to be saved were saved before international agencies arrived.

However, the aid system, with a few exceptions and some emerging ideas, is not a complex adaptive system in relation to poverty and needs. Although things may be improving, the aid system is arguably more adaptive in response to, and ‘tightly coupled’ with the political and financial apparatus of Western states and publics. Chambers 1 argues that the aid sector is ‘a mutually supporting pattern of concepts, values, methods and behaviours which is widely applicable’. Given the limited scope for radical new ideas in this context, the most serious obstacle for application of complexity science for international aid may well be the inability or unwillingness of actors within the system to engage with complexity.

Complexity, for many, is seen as an indulgence. This has led to organisations that are increasingly rigid, risk-averse and bureaucratic; it has meant led to the prevalence of tools and techniques that are linear and simplistic in their scope and outlook2, it has meant change at the level of ideas is much more likely than at the level of ground-level practices3; it means that one can always predict who will do what, when and how4; and it means that the adaptive learning of particular actors are short-circuited, or worse, suppressed. It means that, when mistakes are made in this complex system of governments, NGOs, UN agencies and donors, everyone points the finger at everyone else5.

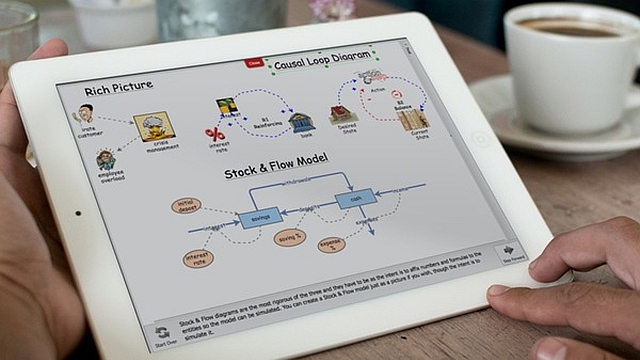

Aside from the political will, there are other more practical issues to consider. Organisations may not have the resources to bear the analytical burden of examining the systems they operate in; most reporting frameworks are geared to a linear mindset; they may not have the scope to incorporate a realistic understanding of the uncertainties of their efforts when planning and implementing projects and programmes; they may not have it in their hands to ensure that those acting to solve a problem address it in a coherent manner; the pressures of accountability to donors or the public may not allow for such uncertainties to be honestly and openly addressed. The following is a summary from a 2004 report on future dynamics of crisis in humanitarian agencies addressing the take-up of complex conceptual frameworks:

Coherent analytical frameworks, while a step in the direction of more effective programs, are no panacea … The challenges for agencies in adopting wider conceptual frameworks are many. Slow uptake may be associated with the burden of more complex analysis and the problems of perceived reliance on outside expertise. A framework requires an elaborate combination of qualitative and quantitative indicators and therefore agencies need to create, teach, develop, sustain, and monitor complex analysis at the national and program levels. Since not all agencies have access to expertise, affiliations with academic or training institutions may be useful. The reluctance to adopt complex frameworks may also reflect an awareness of the difficulties in using these tools for better programming … Agencies need to use these frameworks to advocate and justify more innovative programming. Similarly, donors need to be more flexible and open to tailored responses6

The financial and political costs of bringing such a framework to bear on development and humanitarian problems are far from trivial. As well as use by implementing agencies, an understanding of complexity must also be built into the frameworks of the donors and others who hold the power to determine the shape of development interventions. This may be easier said than done – complexity requires a shift in attitudes that would not necessarily be welcome to many working in Northern agencies. For example, such a shift may require adjusting away from the ‘mechanistic’ approach to policy, or being prepared to admit that most organisations are learning about development interventions as they go along, or being transparent about the fact that taxpayers’ money may be spent on a project that does not guarantee results. It may mean having smaller, but better programmes.

At the same time, though, we see complexity science as having great potential to be misappropriated and misapplied in the aid world, especially given the speed and frequency with which new ideas and approaches are picked up, used, dropped, reused and reformulated.

An even more challenging problem arises from placing international development and humanitarian work in the context of the wider system of international relations within which development and humanitarian work is embedded and by which it is fundamentally shaped. While the emerging ‘beyond aid’ agenda7 shows some hope of this understanding playing a part in the work of at least one major international agency, it is highly unlikely that it will lead to fundamental and comprehensive shifts in foreign policy. Instead, what is likely in the short to medium term is that complexity can support a better awareness as to exactly why development and humanitarian work is so problematic, challenging and hard. If complexity science currently provides greater clarity on why so much in the aid world is wrong, it also points to the kinds of questions that should be asked for things to be put right.

At the start of our exploration, our view was simply that complexity would be a very interesting place to visit. At the end, we are of the opinion that many of us in the aid world live with complexity daily. There is a real need to start to recognise this explicitly, and try and understand and deal with this better. The science of complexity provides some valuable ideas. While it may be impossible to apply the complexity concepts comprehensively throughout the aid system, it is certainly possible and potentially very valuable to start to explore and apply them in relevant situations.

To do this, agencies first need to work to develop collective intellectual openness to ask a new, potentially valuable, but challenging set of questions of their mission and their work. Second, they need to work to develop collective intellectual and methodological restraint to accept the limitations of a new and potentially valuable set of ideas, and not misuse or abuse them or let them become part of the ever-swinging pendulum of aid approaches. Third, they need to be humble and honest about the scope of what can be achieved through ‘outsider’ interventions, about the kinds of mistakes that are so often made, and about the reasons why such mistakes are repeated. Fourth, and perhaps most importantly, they need to develop the individual, institutional and political courage to face up to the implications.

Next part: This article is the final part of the Exploring the science of complexity series. Please also see the three follow-on series:

- Planning and strategy development in the face of complexity

- Managing in the face of complexity

- Taking responsibility for complexity.

Article source: Ramalingam, B., Jones, H., Reba, T., & Young, J. (2008). Exploring the science of complexity: Ideas and implications for development and humanitarian efforts (Vol. 285). London: ODI. (https://www.odi.org/publications/583-exploring-science-complexity-ideas-and-implications-development-and-humanitarian-efforts). Republished under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 in accordance with the Terms and conditions of the ODI website.

Header image source: qimono on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References:

- Chambers, R. (1997). Whose Reality Counts: Putting the First Last, London: Intermediate Technology Publications. ↩

- Bakewell, O. and Garbutt, A. (2005). The Use And Abuse Of The Logical Framework Approach, Stockholm: Sida. ↩

- Killick, T. (2005). ‘Policy Autonomy and the History of British Aid to Africa’, Development Policy Review 23(6): 665–81. ↩

- Seaman, cited in Kent, R. (2004). ‘Humanitarian Futures: Practical Policy Perspectives’, Network Paper 46 (April). London: ODI/Humanitarian Practice Network. ↩

- Smillie, I and Minear, L (2004). The Charity of Nations: Humanitarian Action in a Calculating World, Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press. ↩

- Feinstein International Famine Center (2004). Ambiguity and Change: Humanitarian NGOs Prepare for the Future, Medford, MA: Feinstein International Famine Center, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University. ↩

- Hudson, A. (2007). Beyond-aid Policies and Impacts: Why a Developing Country Perspective is Important, ODI Opinion 79, London: ODI. ↩