3 reasons to study science communication beyond the West

This article is part of a series of articles on decolonising KM.

Lindy Orthia, Australian National University; Dan C H Hikuroa; Ehsan Nabavi, Australian National University; Francesca Rochberg, University of California, Berkeley, and Paula DeVos, San Diego State University

Ask a science communicator how old their field is. They might say a few decades, or even centuries, because they’re thinking about the Western science communication tradition associated with a scientist-public gap.

These days, we almost exclusively associate science communication with Western science. Yet humans have always communicated knowledge about the world within their own societies and to others. There’s evidence of this going back tens of thousands of years.

Society today should recognise past and ongoing science communication approaches that diverge from the West’s relatively recent ones.

Also, as we have explored in a paper and webinar, we should include this knowledge in science communication histories. Here are three reasons why.

1. Framing science as ‘Western’ is political

The histories we tell are political. Political factors can determine important elements such as where a story begins and ends and what is included or excluded. Histories of science aren’t immune to this.

We often equate science and scientific practice with a gold standard of credibility. But there’s much rhetorical power behind the “science” label.

Some influential 20th-century scholars, such as the late British historian Herbert Butterfield, valorised Western science and judged other sources of human knowledge production as failed attempts.

Others such as Andrew Cunningham, while trying to redress that tendency, defined “science” so narrowly that only the Western version of professional knowledge production applied.

Both these stances denigrate non-Western knowledge systems as lesser, by excluding them from “science”.

They have shaped science communication histories taught today, wherein we mostly ignore the diverse ways in which cultures across the world have communicated knowledge.

Thus, most science communicators lack insight into how these cultures tailored their communication to different audiences, aims and mediums.

Did you know medieval European medical writers regularly used Arabic pseudonyms for their published works to confer prestige?

This was because, at the time, Arabic cultures demonstrated strong leadership in pharmaceuticals and other scientific fields across the Afro-Asian-European landmass.

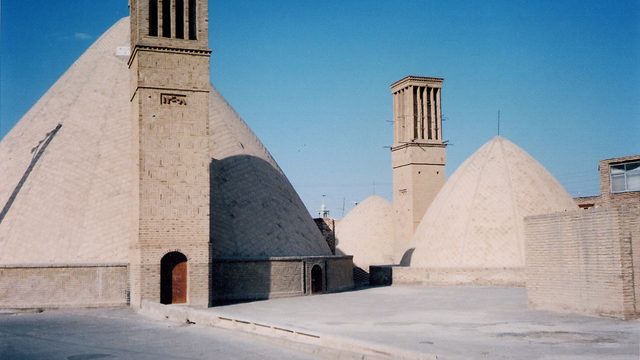

Or consider the Persian engineers who built ingenious constructions to provide water, air conditioning and refrigeration to desert communities thousands of years ago.

They communicated their technical expertise over generations through spoken word and actions.

Such snippets offer deep insight into myriad science communication cultures. Unfortunately, they’re rarely included in science communication histories today.

To borrow from Peter Pormann, a professor of Classics and Graeco-Arabic Studies at the University of Manchester, this is a case of intellectual amnesia.

It may be historians’ wish to respect diverse cultural categories, since “science communication” is an English term associated with Western culture. But a side effect of this is a profoundly Eurocentric approach.

2. Human cultures are diverse and wonderful

All over the world, different science communication systems have been adapted to different locations, lifestyles, cultures and histories. They are manifestations of a glorious wealth of human expertise and creativity and should be celebrated, not ignored.

Some are poetic, some instructional. Some were used to bridge cultures and some to maintain knowledge throughout generations, over centuries and even millennia.

Māori pūrākau (stories) are one example of a narrative technique for communicating mātauranga (Māori knowledge) about the environment, culture, values and more.

Westerners often dismiss pūrākau as myths. In fact, they encode evidence-based knowledge, gathered and tested over many ages, into a metaphor-driven form of communication.

One pūrākau associated with the Waitepuru stream in the Matatā region of Aotearoa New Zealand describes a “taniwha” — in this case a lizard whose tail flicks from side to side.

Among this pūrākau’s many meanings is a warning about the stream’s movement over time, indicating where it’s dangerous to build.

The pūrākau encodes complex hydrogeological knowledge that has been observed, tested and communicated over centuries.

The Māori process of constructing knowledge on the evidence of time-honoured experience is, in fact, consistent with Western science’s expectations of evidence-based knowledge.

Yet, strategies such as pūrākau for communicating that knowledge are culturally-specific and unique. Science communicators should pay them attention as part of the rich diversity of global knowledge communication.

3. Science communication should be inclusive

The past few years have seen the science communication discipline come under heavy fire for exclusionary practices.

The strongest supporting evidence comes from University College London science communication researcher Emily Dawson. She worked with low-income ethnic minority communities in London who weren’t heavily involved in science communication practices.

They didn’t visit science centres or museums. Dawson’s work showed “powerlessness” and “cultural imperialism” (feelings of being “othered”) were key reasons why.

Western science museum exhibits incorporating historical narratives may tell stories about the world from a European perspective. This can perpetuate racism and ratify European colonialism.

If European-descended Westerners are the only demographic who see their culture reflected and respected in science communication histories, this can lead to further social exclusion.

For cultural resilience and continuity, we must support knowledge-keepers’ efforts to sustain their science communication practices.

Even where ancient practices are no longer part of a society’s contemporary life, cultural roots still matter.

For instance, many modern Iraqis have great interest in the 2,000-year-old cuneiform cultures of Babylonia and Assyria. Exploring cuneiform science and its communication practices should be on our collective agenda.

Who had access to Babylonian knowledge about lunar eclipses? Within what worldview did Babylonians frame that knowledge?

These are exciting questions we can and should explore, to ensure the science communication histories we learn and teach leave none behind.![]()

Lindy Orthia, Senior Lecturer in Science Communication, Australian National University; Dan C H Hikuroa, Senior Lecturer; Ehsan Nabavi, Lecturer in Science and Technology, Australian National University; Francesca Rochberg, Distinguished Professor of Near Eastern Studies, University of California, Berkeley, and Paula DeVos, , San Diego State University

Article source: This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Header image: A wall relief from the British Museum shows three scribes amid a military campaign of the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III, in Babylonia (Iraq). Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.