Why do people in organisations withhold their knowledge?

This article is part of a series on knowledge withholding, hiding, and hoarding.

Research that I summarised1 in September last year recommended further investigation into the personal and contextual factors likely to significantly influence engagement in knowledge collection, knowledge donation, knowledge hiding, or knowledge hoarding behaviours. The research had presented a framework establishing the relationship between these behaviours.

A newly published paper2 reports on a systematic review that has further explored personal and contextual factors in regard to knowledge hiding and hoarding, and from this developed an integrative framework that explains why people withhold their knowledge. The systematic review involved the analysis of 42 empirical research papers that had collected data from 16,649 respondents.

While acknowledging that the literature uses the three terms of knowledge withholding, hiding, and hoarding, the authors of the new paper use knowledge withholding as one broad concept. They advise that this is because their systematic review does not provide sufficient evidence to integrate a conceptual distinction between these three terms.

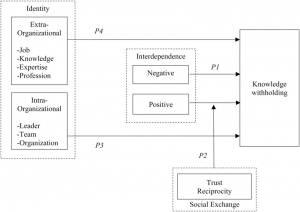

Integrative framework

The integrative framework is shown in Figure 1. Each of P1, P2, P3, and P4 in the framework corresponds to four propositions for which the authors found evidence, as summarised below.

Proposition 1 (P1 in Figure 1): Negative interdependence in the workplace is positively related to knowledge withholding.

There are two aspects to this negative interdependence. The first aspect directly or indirectly reflects (perceived) competition in the workplace. Competition occurs when people see each other as rivals, and so perceptions of competitiveness in the workplace are found to predict knowledge withholding. The second aspect reflects scarcity or uncertainty. When an employee views resources as scarce, threatened, or uncertain, they believe that not all employees can have the resource. One example of a scarce commodity is job security, which people may perceive not all of them can have simultaneously. Knowledge is a means to obtain such a scarce commodity, so withholding knowledge is a rational choice.

Proposition 2 (P2 in Figure 1): When employees (in positively interdependent situations) have positive exchange expectations / relationships, knowledge withholding will decrease, but when they have negative exchange expectations / relationships, knowledge withholding will increase.

Positive outcome interdependence entails that one person’s outcomes are positively interlinked with another person’s outcomes or behaviours, so in situations that are (perceived to be) structured in a positively interdependent way, one person’s success is helped by another person’s efforts or another person’s success. The effect of positive outcome interdependence pivotally depends on the nature of the exchange relationship between the knowledge holder and the potential (non-)recipient. Positive outcome interdependencies may often be the default situation in a workplace because people (e.g., in teams) need to collaborate to attain their goals.

When employees reciprocate and learn that others can be trusted to help them pursue their own goals, withholding knowledge from each other is not an effective means to attaining their own goal and is, in fact, counterproductive. In contrast, when employees believe that other colleagues cannot be trusted or will not reciprocate their help, employees will quickly learn that it is not useful for them to engage in helpful behavior such as sharing their knowledge.

However, what is important to keep in mind is that in positively interdependent situations, employees still depend on others’ behaviour or performance for their success even when they do not trust each other. In these situations, knowledge is likely to be used as a tool or a form of influence, and employees may likely withhold knowledge as leverage to get the knowledge they need from the other party. Hence, in addition to positive interdependence, the nature of the exchange relationship plays a pivotal role in knowledge-withholding behavior.

Proposition 3 (P3 in Figure 1): Employees who strongly identify with their team or organization will be less inclined to withhold knowledge from colleagues.

According to social identity theory, people derive their self-worth from their important group memberships. The groups with which people may identify include their country, work organization, team, profession, or brand identities. Social identity theory can account for the fact that people sometimes act against their self-interest when helping an in-group with which they strongly identify. For knowledge withholding, this means that when individuals identify with their organization, group, work unit, and so forth, they should be less inclined to withhold knowledge from individuals who are part of the in-group.

Proposition 4 (P4 in Figure 1): Employees who identify relatively strongly with people or entities outside their team / organization or who are being excluded from the social identity of their team/organization will be more inclined to withhold knowledge from colleagues.

While social identification focuses a person on positive interdependence between themselves and their group, people do not always identify with the in-group of their immediate colleagues. They may simply not identify with that group, but they may also identify with a completely different group. In the former case, the person is not likely to be motivated to work for the interests of the (immediate colleagues) group. In the latter case, the person may be more likely to consider their interests as negatively interdependent with those of the (immediate colleagues) group. Under these conditions, employees will be more inclined to withhold knowledge from their colleagues, who are, to them, an outgroup.

Article source: Antecedents of Knowledge Withholding: A Systematic Review & Integrative Framework, CC BY 4.0.

Header image source: Robin Higgins on Pixabay, Public Domain.

References:

- Silva de Garcia, P., Oliveira, M., & Brohman, K. (2020). Knowledge sharing, hiding and hoarding: how are they related? Knowledge Management Research & Practice, DOI: 10.1080/14778238.2020.1774434. ↩

- Strik, N. P., Hamstra, M. R. W., & Segers, M. S. (2021). Antecedents of Knowledge Withholding: A Systematic Review & Integrative Framework. Group & Organization Management, 1059601121994379. ↩

Also published on Medium.