Co-creative approaches to knowledge production and implementation series (part 11): An experimental evaluation tool for the Public Innovation Lab of the Uruguayan government

This article is part 11 of a series of articles based on a special issue of the journal Evidence & Policy.

In the second of two practice articles in the special issue, Zurbriggen and Lago1 describe the process that led to the development of an experimental evaluation tool for public innovation as part of an action-research process in a laboratory within the Uruguayan Government. Laboratories in the public sector have emerged as experimental spaces that incorporate co-creation approaches to promote public innovation and social transformation. However, Zurbriggen and Lago alert that although there is abundant literature about public innovation and reports on innovative practices, little progress has been made on how to evaluate these.

Innovation in public policies and services is moving to the top of the agenda at all government levels in many parts of the world. Governments are exploring different ways to involve public servants, the private sector, civil society and academia to play an active role in tackling complex problems. In recent years, a multiplicity of experimental spaces – that is, the laboratories, commonly known as ‘Labs’ – have emerged to promote public innovation and social transformation, incorporating co-creation approaches for the design of public services and policies. The number of innovation Labs in government has rapidly grown in the last decade.

Two Labs born in Western Europe, the MindLab (Denmark) and the Behavioural Insights Team (UK), have been the source of inspiration for governments across the world to re-imagine their public services and create similar initiatives. Some examples include the Seoul Innovation Bureau in South Korea, the Centre for Public Service Innovation in South Africa, the Public Innovation Lab in Chile, the OPM Innovation Lab in Washington D.C., the Co-Lab in Sweden, ARENA A-Lab in Australia, the Laboratory for the City in Mexico City, The Human Experience Lab – THE lab – in Singapore, among many others. Also, different networks have emerged, such as the EU Policy Lab; UNDP and the Sustainable Development Goals-Lab (UNLEASH), to expand this new conception of public innovation.

Influenced by the work of the MindLab, the Uruguayan government launched the ‘Social Innovation Laboratory for Digital Government’ in 2015, within the National Agency of Electronic Government and the Information and Knowledge Society (AGESIC by its acronym in Spanish). The purpose of the Lab is to build a culture of innovation oriented towards the democratisation of public management, based on new paradigms of public intervention that emphasise the active participation of citizens in the construction of services and policies. To this end, the Lab’s strategy is to orchestrate experimental and creative processes to understand, empathise with, and devise solutions to current challenges in digital government.

Zurbriggen and Lago report that the Lab, like many other similar laboratories, faced adversity and frustration when reporting its results to authorities within the organisation, because the rich information emerging from the co-creation processes hardly conforms to the requirements of the dominant instrumental model of evaluation in the public sector. They alert that although involving citizens and other end users in collectively framing problems and bringing forward solutions may be an important ideal, there is little evidence that demonstrates whether this produces better policies and public service innovations. Moreover, they advise that evaluation in this area lacks a theoretical framework.

In their paper, Zurbriggen and Lago focus on describing the process that led to the development of an experimental evaluation tool for public innovation as part of an action-research process in the Lab. The pilot prototype, the ‘Roadmap’ as they named it, seeks to provide a timely and purposeful means to learn from the co-creation processes to communicate results and, thus, be accountable to public authorities and society. To build this tool they drew primarily from the guides and principles of developmental evaluation, organisational learning, and reflexive monitoring. Other relevant approaches to public innovation and evaluation were also considered, such as public design evaluative thinking, social innovation evaluation, and systemic evaluation of learning.

The emergence of the Lab

In the last decade, rich literature about public innovation emerged, framing it as a process of co-creation with citizens having an active role to identify solutions to public problems. The driver of change is therefore the creative and experimental process that involves diverse stakeholders in generating knowledge collaboratively in the production of new services and public policies.

Zurbriggen and Lago state that nevertheless, the concept of public innovation is not new, and its origins can be traced back to the 1980s when the New Public Management (NPM) discourse of ‘reinventing government’ emerged. Such discourse was followed by the creation of several public innovation labs seeking to make governments more efficient. Public innovation is narrowly defined in NPM as new or improved services and policies, where public servants apply forethought to guide agency action to solve problems.

However, Zurbriggen and Lago advise that contemporary approaches to public innovation distance themselves from NPM because, instead of resorting to scientific evidence-based policy making, contemporary approaches are grounded on a strong experimental orientation to policy and service design. These emerging experiment-oriented approaches to policy design reveal the ‘sensemaking policymaker’ who practises design-intelligence-choice.

Labs provide the necessary ‘room’ to develop these new ways of doing things in government, performing processes of experimentation where a solution concept (an idea, design, program, project, and so on) to a particular problem is created, and iteratively refined based on continuous feedback from the stakeholders immersed in the experiment.

Uruguay has turned into a regional and global reference in digital government, becoming the first Latin American country to be part of the most advanced digital nations network, the Digital 9 (D9) in 2018. In this context, the Social Innovation Laboratory for Digital Government (in short named the Lab), was created with the purpose of supporting Uruguay’s digital government strategy by experimenting with the uses and applications of digital technologies in people’s daily lives, applying co-creation methodologies. It seeks to promote and disseminate the principles of public and social innovation to improve internal processes, policies and public services.

The Lab developed an experimental strategy of intervention which is adaptive to each project and unfolds in four phases: understanding, empathising, devising and experimenting. The strategy aims to innovate in tools and techniques based on different design approaches (for example, design thinking, human-centred design, usability, accessibility of users, agile methodologies, games, among others) and harnessing the team’s diverse disciplinary backgrounds in Anthropology, Social Psychology, Ethnography, Communication, Design, and Engineering.

Until now the Lab has assisted in the digitisation of administrative procedures across all sectors in government, incorporating diverse stakeholders’ insights and experiences to provide better user-friendly solutions, as well as optimising time and reducing paper use. As a result of the project ‘Online Procedures’, the Lab has run 39 co-creation workshops to redesign these services with the participation of 154 public servants and 83 citizens; 50 prototypes were created, and today 33 new procedures are online.

Challenges in public innovation evaluation

Zurbriggen and Lago alert that a key characteristic of a public innovation initiative is that it is rarely clear how or if it will lead to a specific result at all, because of the multiple interactions and potential conflicts arising from values and perceptions in dispute. Furthermore, when a public innovation experiment is subjected to the dominant model of evaluation that focuses on outputs rather than outcomes, emergent learning processes are neglected and the data obtained can be biased in an effort to produce measurable results, which can ultimately affect the innovation process itself.

Despite the support that the Lab has received from inside and outside the government, it has found ‘barriers’ in its institutional insertion due to traditional public organisations’ management idiosyncrasy: adversity to risk and limited tolerance to failure, resistance to change, and bureaucratic/administrative routines. Consequently, it became strongly dependent on political support to thrive in the face of cultural resistance and the lack of a shared language.

Public innovation labs often confront the risk of being isolated from their parent organisation, which limits their overall impact on innovation capacity and questions the sustainability of innovation in the public sector. The Lab is not an exception to this. Since its creation, it has been tackling the challenge of legitimising itself and demonstrating (successful) results within AGESIC, as well as to other national authorities and financing international organisations.

Given the strain between the difficulties of conforming to the requirements of instrumental evaluation and the growing concern to better reflect their outcomes, in 2017, after two years of operation, the Lab enlisted a team from the University of the Republic to work with them on designing an evaluation tool tailored to the organisation.

University of the Republic researchers Zurbriggen and Lago proposed to develop a pilot, a Roadmap, as they named it, to guide the Lab in harnessing learnings from co-creation processes and communicating public innovation outcomes to government authorities and the broader audience. The project was conducted from February 2017 to February 2018, and was based on an action-research approach, focusing on social learning and context adaptation.

To develop the Roadmap, Zurbriggen and Lago were embedded in the Lab routines for a year. The process of research included fieldnotes and photographs; documents produced with the Lab such as presentations, project briefs, reports, summaries of meetings and emails. In addition, they conducted participant observation, semi-structured interviews with the Lab’s team (6), civil servants (9), and stakeholders (10), who participated in the Lab’s co-creation workshops, as well as with the directors of three Latin American Labs (Chile, Argentina and Colombia). The Roadmap was designed through iterative cycles of literature review, identifying relevant themes in the evaluation process, sharing them with the Lab team, triangulating with information arising from interviews, and referring back to scholarly and grey literature.

The rationale behind the Roadmap

In order to design a purposeful evaluation and monitoring tool for the Lab, Zurbriggen and Lago started by exploring new conceptual frameworks about innovation evaluation.

One of the most significant of these frameworks is ‘Developmental Evaluation’, which informs and supports innovative and adaptive interventions in complex dynamic environments, in real time. This model seeks to achieve changes in the way of thinking and behaviour of the stakeholders, and in the procedures and organisational culture resulting from the learning generated during the evaluation.

In Developmental Evaluation, the unit of analysis is no longer the project or programme, but the system. Developmental Evaluation is not about ‘testing’ a model of evaluation, but about generating it constantly. Therefore, this model is more appropriate than instrumental evaluation techniques to account for systemic change and deal with the unexpected and unpredictable.

Evaluation for strategic learning entails a process of acting, assessing, and acting again; it is an ongoing cycle of reflection and action. Strategic learning is a form of double loop learning. Single-loop learning takes place when an organisation detects a mistake, corrects it, and carries on with its present policies and objectives. Double-loop learning occurs when an organisation detects a mistake and changes its policies and objectives before it can take corrective actions. In strategic learning processes the integration of explicit knowledge (codified, systematic, formal, and easy to communicate) and tacit knowledge (personal, context-specific and subjective) is crucial.

Based on this new evaluation paradigm, and the Lab’s concerns and requirements, Zurbriggen and Lago and the Lab jointly decided that the evaluation proposal should contribute to its strategic learning process in order to improve systemic innovation. The Roadmap, validated not only with the Lab but also with AGESIC authorities, highlights the importance of processes of collaborative knowledge creation instead of focusing on objectives.

The fundamental principle underlying this evaluation pilot is to assess the learning capacities for systemic change and to produce collective knowledge that supports the team when making decisions. The evaluation seeks to address one of the organisation’s main challenges, such as the evaluation of co-creation processes and transdisciplinary knowledge generation, which is the basis of the Lab’s strategy. Zurbriggen and Lago therefore assumed that there is a reciprocal relationship between strategy and evaluation because when both elements are comprehended and carried out in this way, the organisation is better prepared to learn, grow, adapt and continuously change in meaningful and effective ways.

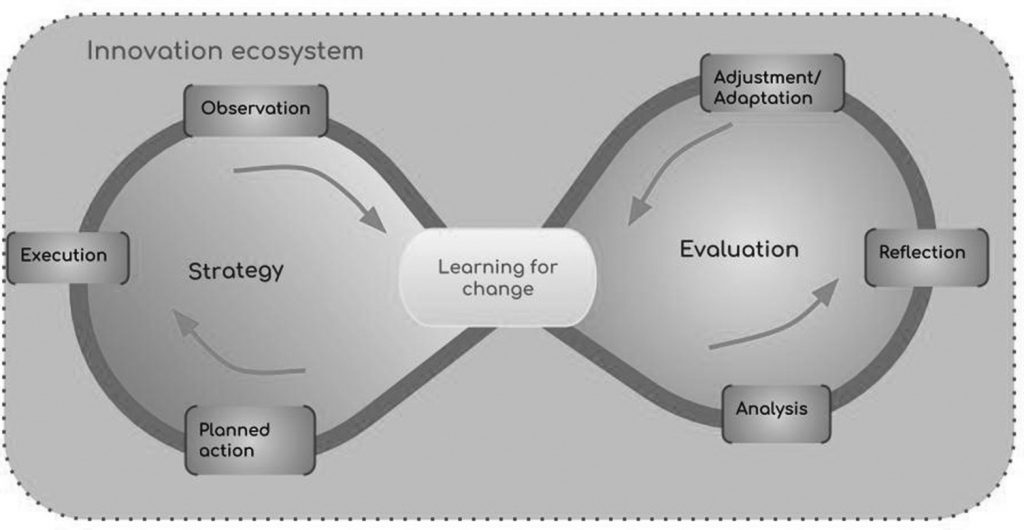

In the Roadmap, Zurbriggen and Lago assume there are two major interconnected phases in the learning process occurring within the innovation ecosystem where the Lab is inserted (Figure 1). The first phase involves the evolution of the strategy in which, after the execution of the planned actions, the team observes how the planned strategy unfolded. From the observation emerges the second phase in which the team analyses and reflects about the process to identify which elements of the planned strategy could be realised, which could not and which new ones emerged to adjust and adapt future actions. The learning for systemic change results from the interconnectedness of this two-fold process. This is a living model rather than a static one, and is thought to be an integral part of the Lab’s core tasks as it informs and supports continuous innovation.

As innovation takes place under uncertainty, the actions carried out are experimental and demand constant reflection to understand what is happening in the process. The double-loop learning cycle is crucial to have the necessary information about how the strategy is unfolding and the resulting lessons (for example, to develop new tools for citizen engagement and participation). The evaluation is intentional about the use of data in a meaningful way to inform the process of innovation and identify emerging patterns and learn.

Thinking about the conditions and capacities for learning must be, therefore, the first and constant exercise of the Lab’s team. Reflecting while the actions unfold (barriers and opportunities), enables generation of the necessary adjustments and adaptations to change the rules of the game. In this process, specific interventions can result in new rules, practices and relationships within the organisation and the network of actors involved. Therefore, system learning needs to assess whether the current and relatively stable set of social structures is being challenged, and what new knowledge, actions and practices are emerging.

The roadmap is ‘co-adaptive’ in order to meet the team wherever they may be in the project cycle and fit easily into the Lab’s organisational process. The guidelines included in the prototype were developed to have a more purposeful and nimble impact to support projects with timely feedback. Consequently, the Lab can improve methods and tools by integrating emerging information in continuously changing environments.

The Roadmap design and validation process

A critical challenge when designing the Roadmap was to ensure its integration into the Lab’s routines. To secure the appropriation of the new tool by the team, the design process underwent a series of stages: first, based on the review of literature and interviews with the team, Zurbriggen and Lago designed the pilot prototype presented above. Second, the pilot was analysed in three consecutive workshops in order to warrant the feedback process. In these events, apart from the Lab team, relevant stakeholders (AGESIC authorities, practitioners in the field of social and public innovation, and Lab workshops prticipants) were invited. In total, 32 people participated in the three workshops (12, 10 and 10 respectively).

Prior to the first workshop, which was held in October 2017, a document containing the conceptual framework supporting the prototype was created and discussed with the Lab team. During the workshop, the participants worked on understanding the rationale behind the proposed tool, and on identifying the Lab’s conditions and capacities for learning. Some of the triggers for the discussion were: What have we learnt from the co-creation processes and what outcomes can be connected to decision making? What evidence would indicate that a Lab’s co-creation process is working or not? What have we learnt from our success and failures? What are the real-time feedback mechanisms of the organisation to track changes? What unforeseen events occurred and how did we respond to them?

A second workshop took place in March 2018, with the goal of reflecting on the system where the Roadmap would be immersed and the capacities and conditions of the Lab for learning. First, Zurbriggen and Lago focused on the innovation ecosystem by paying close attention to current conditions in its subsystems: a) the institutional-political context; b) the innovative culture subsystem; c) the Lab-experimental strategy.

For each of these subsystems, Zurbriggen and Lago proposed a series of trigger questions for their assessment:

- For the institutional-political context subsystem, the key issues to answer were: What institutional and systemic factors, such as policies, regulations, resource flows and administrative practices need to be in place to support, expand and sustain innovation? What are the obstacles and incentives for public innovation (in the AGESIC and with other sectors of government)? How is innovation organised to work collaboratively with other actors, government officials, citizens and the private sector?

- For the innovative culture subsystem, the key questions were: What cultural attributes, beliefs, narratives and values are required for public innovation to thrive (in the AGESIC and with other sectors of government)? Where do they exist and where do they meet resistance?

- For the Lab-experimental strategy subsystem, the key questions were: Do we have a clear strategy for the Lab? What aspects of the plan could be executed? What had to be ruled out and why? What adaptations have been made? What resources, skills, networks and knowledge are required in the public sector to support the scaling of innovation?

From this collective discussion, the Lab team proposed to introduce a qualitative self-evaluation online form to systematise the information of the ecosystem and to analyse it in their annual meetings with AGESIC authorities. The members of the team would answer the questionnaire, and the set of questions discussed during the workshop were reduced and simplified to the following (aiming to cover each subsystem):

- How does the political and legal context hinder or encourage innovation in the Lab?

- Have we developed a shared language and vision concerning the Lab practices?

- Concerning the strategy the three critical questions are: Why are we practising public innovation? How are the short- and medium-term objectives linked to the theory of change? What actions do we need to take to achieve these short- and medium-term objectives?

Finally, a third workshop took place in April 2018. After iteration and adaptation of the tool based on the feedback received on the first and second workshop, as well as on the continuous dialogue with the Lab team, Zurbriggen and Lago focused, on this occasion, on the validation of the prototype. This workshop was conducted using a design game method developed by the Lab to simulate the process of evaluation (Figure 2). Design games are a form of instrumental gaming data in experimental and innovative contexts for creating a common language. The activities usually involve relevant stakeholders and end users in both product and service design processes, through dialogue material to improve creativity. This board game was initially created with the aim of building co-creation capabilities among public servants. Through the game, the players would become familiar with the different stages of the co-creation process.

Zurbriggen and Lago adapted the board game and used it in the workshop to identify in which parts of such process the Roadmap should be integrated and how. As a result, it was recognised that it should play a critical role in monitoring the strategy while it is unfolding and assessing the experiments conducted by the Lab (for example, the introduction of new co-creation methods and tools). With regard to the experiments, the Roadmap serves to assess the capacities for learning by focusing on two outcomes: internal learning, aiming to capture the Lab team’s reflections at the beginning and end of each co-creation project, and external learning seeking to apprehend the participants’ reflections before and after attending the co-creation workshops.

For internal monitoring of learning capacities, an online protocol for each experiment will be implemented. It is to be responded to by members of the team involved in each project, and it contains the following information:

- General project information (name of the experiment, participants, sector, time of development)

- Pre-experiment questions: What is the activity that we are going to develop and why? What do we expect will happen (hypothesis)? How are we going to do it (method, tools)?

- Post-experiment questions: What unforeseen factors emerged and how did we adapt to them?

For the external evaluation of learning capacities, participants of the workshops will be required to answer an online questionnaire with the following questions:

- How useful was the activity?

- Did the co-creation process seem appropriate for the problem/s to be addressed?

- Was there an adequate treatment (respectful, humble, inclusive) of emerging ideas during the workshop by the Lab team?

As an incentive for participants’ response to the evaluation, they will receive an attendance certificate.

In synthesis, the process of designing the Roadmap led not only to the development of a monitoring and evaluation tool tailored to the organisation, but also to acknowledge the necessity for a more robust information system for decision making. The Roadmap as an information system per se will be complemented with online protocols and questionnaires to assess the Lab’s innovation ecosystem, strategy and experiments.

Next and final part (part 12): What next?

Article source: Adapted from the paper An experimental evaluation tool for the Public Innovation Lab of the Uruguayan government published in the Evidence & Policy special issue Co-creative approaches to knowledge production: what next for bridging the research to practice gap?, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Acknowledgements: This series has been made possible by the publication of the special issue as open access and under a Creative Commons license. The guest editors and paper authors are commended for their leadership in this regard.

Header image source: Adapted from an image by Michelle Pacansky-Brock on Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

References:

- Zurbriggen, C., & Lago, M. G. (2019). An experimental evaluation tool for the Public Innovation Lab of the Uruguayan government. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 15(3), 437-451. ↩

Also published on Medium.