Critical Eye: Tacit knowledge paper gets lost in neuromyths, highlighting issues with evidence quality in KM

This article is part of two ongoing series of articles: Critical Eye and Evidence-based knowledge management.

My research for RealKM Magazine often takes me into Google Scholar, where my searches mainly involve looking for newly published academic journal review papers on the range of topics related to knowledge management. I primarily look for systematic reviews1, which produce a reliable knowledge base through appraising and summarising the findings of a range of studies. However, I also consider narrative reviews, and sometimes also single studies if the research findings are significant or relate to prominent issues being debated at the time by the knowledge management (KM) community.

But wait…

But before I can use any of the academic journal papers that I locate, there’s an important step that I must take. This step is the third of the six steps of evidence-based practice, and involves critical appraisal of the potential evidence to judge its trustworthiness, value, and relevance in a particular context. To be able to critically appraise a journal paper, I have to be able to read all of it, so I can only consider papers that are open access.

The initial questions that I then ask as part of the critical appraisal of the open access papers I locate are in regard to the reliability of the source and the publication dates of the paper and the evidence and references is uses. Has the paper been published in a known, reputable source, for example one of the highly-ranked peer-reviewed KM journals2, or in the preferably peer-reviewed proceedings of a highly-regarded KM conference? Are the paper and the references and evidence it uses up-to-date?

Evaluating the reliability of the source is very important because, unfortunately, predatory journals and predatory conferences are a reality, and papers from them are indexed by Google Scholar. An example is the Google Scholar listing of the paper3 “Understanding knowledge management in academic units: a framework for theory and research.” This paper is published in the European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, which appears in Beall’s list of potential predatory journals.

Using up-to-date evidence is very important because more recent research improves on, or can even refute, the findings of earlier research. A general rule of thumb is to avoid sources published more than around five years ago unless there is a specific and valid reason for using older sources, for example the conduct of historical research.

If a journal paper passes the initial questions, then a thorough review begins. The Center for Evidence-Based Management (CEBMa) has a number of questionnaires that can assist you with your review. The questionnaires are based around these general appraisal questions:

- How was the outcome measured?

- Is that a reliable way to measure?

- How large was the effect size?

- What implications does the study have for your practice? Is it relevant?

- Can the results be applied to your organization?

Each questionnaire deals with a different type of study, for example one questionnaire provides a checklist for the appraisal of a meta-analysis or systematic review, and another a checklist for a case control study. There isn’t a questionnaire addressing conceptual studies, a type of study commonly encountered in KM, but other guidelines exist.

If a paper fails to pass either the initial questions or the thorough review, then the response is simple. Don’t use it. This applies even if the paper contains some useful information, because using or referencing it will give it value in the eyes of others, and unlike you, many of those other people will not know which parts of the paper are good and which parts are not.

Alarm bells

A single study KM research paper that I recently located clearly illustrates why evidence must be critically appraised before a decision is made to use it.

The paper4 is “Reassessing Tacit Knowledge in the Experience Economy,” published in Integrated Economy and Society: Diversity, Creativity and Technology, Proceedings of the MakeLearn and TIIM International Conference, 16–18 May 2018, Naples, Italy. The acronym TIIM stands for Technology, Innovation and Industrial Management.

The paper title caught my eye because of the focus on tacit knowledge in the context of the experience economy. At the time I located it I was preparing for my “Transforming mindsets – leading the way with innovation” masterclass at the Knowledge Management Singapore 2018 (KMSG18) conference. I was trawling Google Scholar to see if any new relevant research papers had been published in the few months since I developed the university knowledge management and innovation class on which the masterclass was based. Four of the ten types of innovation relate to the experience economy, so a paper exploring tacit knowledge in the context of the experience economy was potentially very valuable.

I first asked my initial questions. Has the paper been published in a known, reputable source? Are the paper and the references and evidence it uses up-to-date?

The KM conference at which the paper was presented is the MakeLearn & TIIM International Conference, which is organised by the International School for Social and Business Studies (ISSBS) in Slovenia in cooperation with international partner universities. In 2018, these partner universities were Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Poland; Kasetsart University, Thailand; and Pegaso Online University, Italy. The MakeLearn & TIIM International Conference has been convened for a number of years, and is highly regarded by the academic community, being supported by an Honorary Board and Programme Board made up of a large number of academics from universities around the world.

The conference proceedings are also peer-reviewed. The Quality Assurance Policy for the forthcoming 2019 MakeLearn & TIIM International Conference states that:

the author may submit a full paper which is subjected to a double-blind review process. Full papers are evaluated based on originality, clarity, methodological standards of a research paper, significance of their findings, and clarity of exposition …

Conference Proceedings include full-length papers as well as abstracts that have successfully passed the review process or evaluation. Proceedings are published in electronic form and have all the features of an academic publication, including its own ISSN number which introduces it into a fully refereed conference publication.

Moreover, MakeLearn & TIIM conference announces best paper awards, which additionally strengths [sic] quality of the event.

The paper was published this year. A number of the references used in the paper were published in the last five years, but quite a few other references are more than ten years old, which is a concern. However, some of these older references relate to landmark research that is directly relevant to the topic of the paper, for example research where Ikujiro Nonaka is lead author. So the paper could only be considered to be somewhat up-to-date, and I would need to keep this in mind as I then progressed to the thorough review.

I then commenced the thorough review, and sadly it wasn’t long before the alarm bells started to ring in my mind. I was very concerned to read the following text in section 4 of the paper:

As we, the humans, use only a fraction of our brain capacity, if we do not tap into the currently underutilized mental resources that have been removed from our consciousness by sociocultural programming, there is a serious possibility that we can be entirely replaced by machines.

As well as no reference to support the strong claim that it’s possible we can be entirely replaced by machines, the text contains the statement that “we … use only a fraction of our brain capacity.”

This statement is unfortunately one of a number of what are known as “neuromyths,” which are common misconceptions about how our mind and brain functions. You can complete a test on Quartz to find out how many of several of the most common neuromyths you believe. A healthy human actually uses 100% of their brain, rather than “only a fraction” as the paper incorrectly states.

The alarm bells then rang even more loudly when I read further, and encountered the following statement in section 5 of the paper:

To this end, they must rely heavily on advanced left-brain-based technologies while building extremely sophisticated social structures relying on non-cognitive traits of the human psyche.

And then this text at the end of section 5:

Once a successful interface of the AI with human brain is invented, it can potentially liberate the untapped resources of human intelligence and creativity, provided we have a good insight into how human non-cognitive (right) brains function and how they interface collectively with each other. In any case, right brain is the natural habitat of tacit knowledge, which, being in its essence cultural, contextual, experiential, social, emotional, attitudinal and conceptual, belongs precisely there.

And then a number of other statements in regard to “right brain” function right through to the conclusion at the end of the paper.

The notion that creativity and emotion are located in the right half of the brain while rationality and logic are situated in the left half of the brain is unfortunately also a neuromyth.

So the paper failed the thorough review, meaning that I couldn’t used it.

Where did they go wrong?

How did the authors come to feature neuromyths so prominently in their paper? As these neuromyths are common misconceptions, the authors may have believed them before they wrote their paper. However, I don’t know that, so if I was to draw any conclusions in that regard then I’d also be guilty of making statements that weren’t evidence-based.

However, a clearer contributing factor can be found in the following statement in the conclusion of the paper:

As many jobs, including the most complex ones, are gradually replaced by artificial intelligence and smart technology, organizations and individuals will have to adapt to the new work realities by unleashing their right-brain creativity. (Pink, 2006)

The reference for this statement is:

Pink, D. (2006). A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future. New York City: Riverhead Books.

The publication date of 2006 makes this book more than ten years old, and as I discussed above, this means that there is already cause for concern.

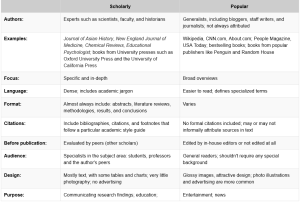

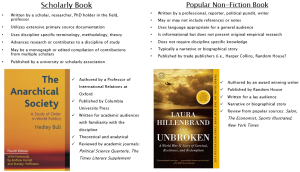

Beyond this, can the book be considered an appropriate scholarly source? An academic paper can use both “scholarly” and “popular” reference sources (Figure 1). Scholarly sources should primarily be used, but popular sources can also be appropriate, depending on the research question.

In regard to books, there are clear differences between scholarly and popular works (Figure 2), and an academic paper should primarily reference scholarly books rather than popular books.

The Amazon listing for Daniel Pink’s A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future states that the book has drawn “on research from around the world.” I can’t access the book to assess the quality of that research, and it’s possible that Pink used “right brain” as a metaphor.

Regardless, Pink’s best-selling book is primarily popular non-fiction rather than a scholarly source, and was an inappropriate reference for a peer-reviewed conference paper on knowledge management. As a Harvard University educational resource alerts:

“Right-brainers will rule the future,” declares Daniel Pink.

Although such statements are likely meant as metaphors to suggest that those who can think creatively and empathically will become increasingly important to businesses, they lock us into ways of thinking about brain function that reduce our understanding of the brain and, therefore, limit our ability to develop more effective models of education. The left-brain/right-brain metaphor puts us into the very box out of which we encourage creative people to think.

It’s also clear that the paper authors didn’t see “right brain” as a metaphor, as evidenced for example by the following statement at the end of section 5:

right brain is the natural habitat of tacit knowledge, which, being in its essence cultural, contextual, experiential, social, emotional, attitudinal and conceptual, belongs precisely there.

The authors should not have made such neuromyth-based statements in their paper. But if they did, the peer-reviewers of the paper and the universities that co-organized the conference should have identified the neuromyths and requested that the authors make corrections to the paper.

Some things to keep in mind

This example of the use of neuromyths in the paper “Reassessing Tacit Knowledge in the Experience Economy” alerts us to some things we need to keep in mind when considering what evidence to use in evidence-based KM:

- All of the evidence we use in KM practice needs to be critically appraised to judge its trustworthiness, value, and relevance in a particular context.

- Common misconceptions can negatively influence research and the application of research findings to KM practice. We need to be ever-vigilant in this regard.

- While Google Scholar is a useful tool for locating KM research as part of evidence-based practice in KM, some of the research indexed by Google Scholar can’t be trusted.

- Peer review isn’t perfect, and neither are universities. While peer-reviewed research published by a university is likely to be of much higher quality than other potential reference sources, be aware that “meeting all of the criteria for a scholarly source is not an absolute guarantee of good scholarship. Aim to use the highest quality information but subject everything to critical scrutiny.”

Header image source: Adapted from Evidence Based by Nick Youngson on Alpha Stock Images which is licenced by CC BY-SA 3.0.

References and notes:

- Briner, R. B., & Denyer, D. (2012). Systematic review and evidence synthesis as a practice and scholarship tool. Handbook of evidence-based management: Companies, classrooms and research, 112-129. ↩

- Serenko, A., & Bontis, N. (2017). Global ranking of knowledge management and intellectual capital academic journals: 2017 update. Journal of Knowledge Management, 21(3), 675-692. ↩

- Because the paper has been published in a potentially predatory journal, it has not been referenced here. ↩

- Because the paper fails critical appraisal, it has not been referenced here. ↩

Also published on Medium.