Case studies in complexitySystems & complexity

Case studies in complexity (part 6): Tacit knowledge transfer and deliberative conversations in the Helidon Hills

This article is part 6 of a series featuring case studies in complexity from the work of RealKM Magazine’s Bruce Boyes.

Background

- Helidon Hills. The Helidon Hills1 is located about 100km west of Brisbane, the capital city of the Australian state of Queensland. It is one of the largest areas of mostly continuous native forest still remaining in the southeastern region of Queensland, and has a large number of rare and threatened flora and fauna species. This includes a large number of species that are found only in this area, for example Eucalyptus helidonica2.

- Sustainable management project. Recognising the values of the Helidon Hills and the need to conserve them through the sustainable management of the area’s various land uses, the Western Subregional Organisation of Councils (WESROC) implemented the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills project3 in 1998-1999. I was appointed as Project Coordinator, with support from two part-time staff seconded from Queensland Government agencies.

Why it’s complex

- Competing and conflicting objectives. The Helidon Hills area is one-third National Park and two-thirds private freehold land. The approximately 250 freehold landholders were engaged in a range of pursuits including timber harvesting, sandstone mining, ecotourism, nature conservation, and farming. Some of these pursuits were competing or in direct conflict with each other. The area also has Aboriginal and European cultural heritage. Management policy for the area was the responsibility of various local governments and state government agencies. This divergent array of objectives and perspectives made it very difficult to find a way forward that would not be opposed by at least some of the landholders and/or land managers.

- Lack of understanding and awareness. Compounding the complexity of widely divergent objectives and perspectives, it was apparent at the commencement of the project that most stakeholders lacked important knowledge in regard to the Helidon Hills area. Many stakeholders had a poor understanding of the natural values of the area and what needed to be done to conserve them, and a low awareness of the activities and issues of concern of other stakeholders. (In nature conservation in Australia, the term “stakeholders” is used to collectively refer to the people within an area or with an interest in an area, and in this case included landholders, government agency representatives, and members of the wider community).

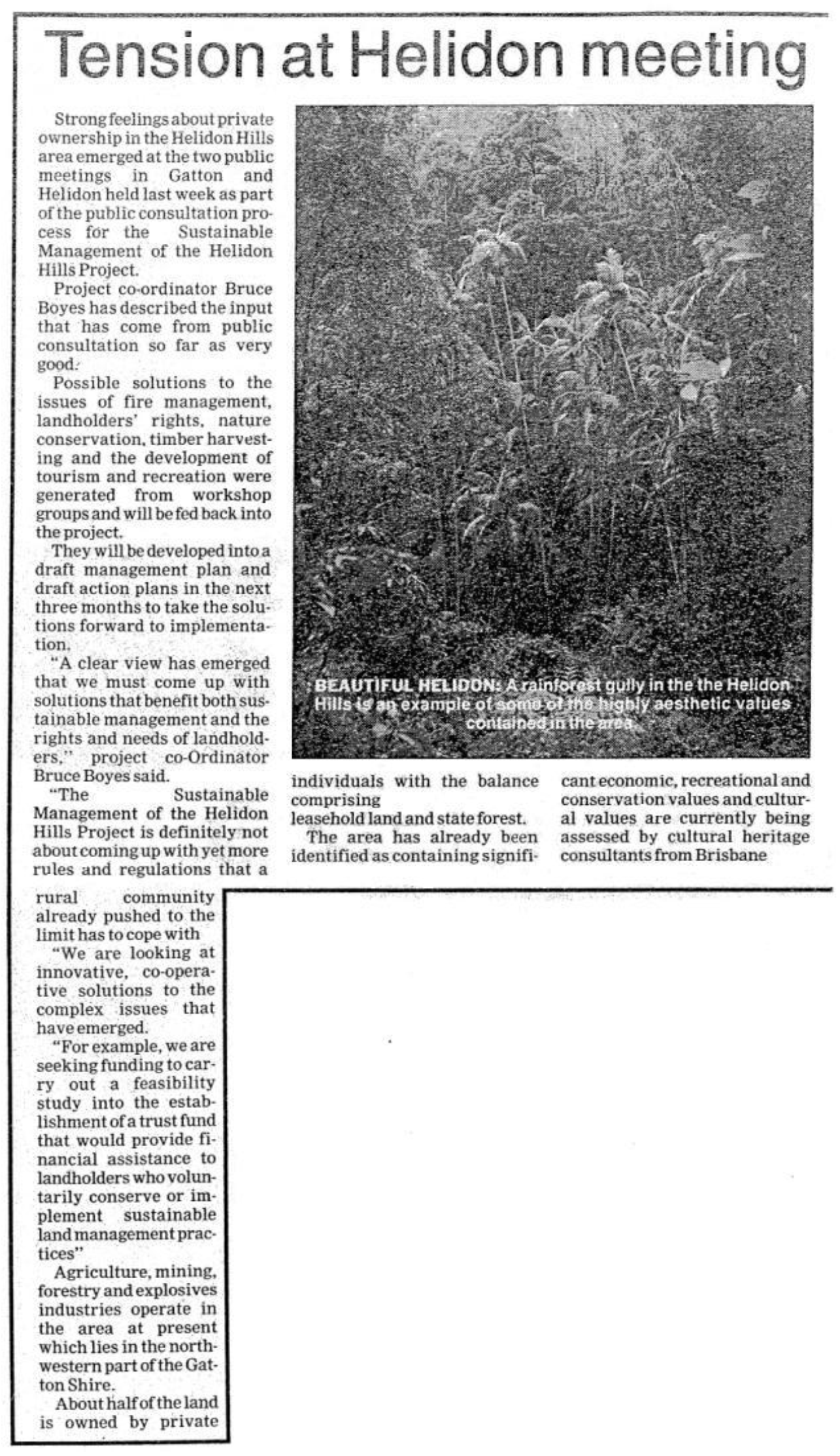

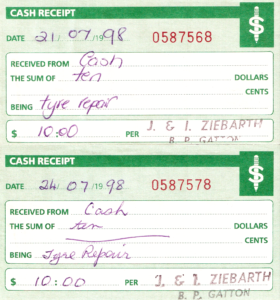

- Landholder rights and disenchantment with mainstream government. At the commencement of the project, some landholders expressed strong opposition to it. Particularly strong feelings were evident in regard to private land ownership, with the view expressed that people should have the right to manage their land as they see fit without any government influence, control, or intervention (Figure 1). This opposition was symptomatic of community disenchantment with mainstream government in the wider area and in some other parts of Australia at the time, with the project coinciding with the rise of the controversial One Nation political party4. During the course of the project, the Lockyer State electorate, in which most of the Helidon Hills was located, elected a One Nation candidate as its local member. This community disenchantment with mainstream government added to the complexity faced by the project, for example, early in the project I experienced acts of attempted intimidation including death threats and the spiking of the rear tyres of my car (Figure 2).

- Rural decline. A number of authors have attempted to explain5 the voter support received by One Nation. However, from my own experiences and observations, the support for One Nation in the Lockyer electorate and associated values position against government programs such as the Helidon Hills project was due to the declined emphasis on agriculture since the 1970s6, the impacts of the recession of the early 1990s, and government programs that had not adequately involved the community. Most of the farming families in the Lockyer were second or third generation, and adapting to the decline of agriculture from the heydays they had previously experienced was difficult. The recession of the early 1990s compounded the difficulties. Further compounding the pressure that the community was feeling were government programs such as the mid-1990s Regional Open Space Scheme7 which triggered a backlash because it had not effectively engaged the community.

Approach

- Protecting nature conservation and cultural heritage values. An initial action I took was to decide that the nature conservation and cultural heritage values of the Helidon Hills area must be protected as a non-negotiable given, based on studies and assessments by ecological scientists and cultural heritage experts in consultation with First Nations representatives. There are very sound evidence-based reasons for this. Environmental management in Australia is extremely poor, with the country having one of the world’s worst biodiversity conservation records9. Protecting the conservation values of areas such as the Helidon Hills is essential if Australia is to halt and then ultimately reverse its worsening biodiversity crisis. Similarly, Australia has a shocking record of Indigenous heritage destruction10 that needs to be halted.

- Recognizing and respecting landholder rights. A further initial action I took was to commit to recognizing and respecting landholder rights in the project, in response to the strong concerns expressed at the commencement of the project in regard to private land ownership (as discussed in the “Why it’s complex” section above). Consequently, the management plan (see below) devotes an entire chapter to the issue (Chapter 3).

- Tacit knowledge transfer. In addition to convening twice as many public meetings as had been originally planned, I then talked directly with as many people within the area and with an interest in the area that I could. This involved discussions individually (such as with individual landholders and state and local government agency representatives) and in groups (such as with the sandstone miners and people with an interest in ecotourism). These direct discussions had the purpose of two-way knowledge transfer: me educating stakeholders in detail about the nature conservation and cultural heritage values of the area, and, very importantly, them giving me an in-depth and nuanced understanding of their land use and land management intent and issues. As discussed in part 7 of this RealKM Magazine series, I used problem-solving communication skills to significantly increase the effectiveness of the discussions. To the greatest extent possible, I met people onsite – such as on their property, at their sandstone mine, or at their timber mill – because tacit knowledge can’t be effectively transferred using just words. Collectively experiencing the nuances and intricacies of land use and land management issues directly facilitates tacit knowledge transfer. To encourage people to engage in the public meetings and direct discussions, landholders and other stakeholders were sent newsletters inviting participation and contact. The newsletters included “Have your say” forms so that people could provide written input if they preferred. The forms could be mailed back or returned at comment stations established in public locations in towns adjacent to the area. Copies of the newsletter were placed at the comment stations to enable members of the wider community to provide comment and/or make contact to request discussions. The public meetings used the nominal group technique11.

- Deliberative conversations. Finally, I facilitated numerous deliberative conversations to chart agreed ways forward that both protected the values of the area and maximized stakeholder land use and land management objectives. This included bringing people with conflicting issues together to work through and resolve their concerns in creative friction. The conversations created space for the emergence and development of win-win solutions to address the issues that were identified in the tacit knowledge transfer step above. All of the deliberative conversations were facilitated on-site in the Helidon Hills because, as with tacit knowledge transfer, emergence can’t occur using just words. Collectively experiencing the nuances and intricacies of land use and land management issues while seeking ways forward in addressing them facilitates emergence. A notable aspect of the deliberative conversations was that many people ended up having far more common ground than they had first expected. As discussed in part 7 of this RealKM Magazine series, I used problem-solving communication skills and lateral thinking to significantly increase the effectiveness of the deliberative conversations. For example, to address the rural decline issue discussed in the “Why it’s complex” section above, the win-win solutions identified through lateral thinking included establishing new environmental tourism enterprises in the Helidon Hills and a Centre for Native Floriculture at the nearby University of Queensland Gatton Campus.

- Draft management plan. The Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Draft Management Plan12 prepared from the above process was different to what might be expected for such a plan. Rather than specifying outcomes, the plan recognized that outcomes were a long way off, and instead describes a framework and ongoing tacit knowledge processes for achieving sustainable management that is sensitive to the diverse interests of the area and creates space for the adaptive ongoing emergence of win-win solutions. Direct quotes of stakeholder knowledge appear throughout the plan.

- Coordination body. Recognising that the tacit knowledge processes described in the management plan needed ongoing human coordination, landholders established the Helidon Hills / Murphy’s Creek Landcare Group at the end of the project to coordinate the ongoing implementation of the plan.

Outcomes

- Significant praise. The Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills project was very successful, receiving significant praise from the local government that had hosted the project, as shown in the newspaper article excerpt below (Figure 3).

- Pioneering work on tacit knowledge engagement and emergence in the face of complexity. The approach I took in the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills project was innovative pioneering work at the time. It was inspired by my earlier such work on the WWF South-East Queensland Vineforests Project (1996-1997), which had in turn been inspired by my experiences of collaborative knowledge co-creation in the Ipswich Heritage Program (1991-1994) and my earlier experiences with complexity in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) (1982-1991). The approach I took was several years ahead of similar approaches to complexity that would be documented later: probe, sense, respond13 in organizational knowledge management (KM) (2007), collaborative learning and governance14 in environmental management (2009), decisions from deliberation15 in international development (2011), and multiple knowledges and multi-stakeholder processes16 in KM for international development (2013).

Lessons

- Not transforming tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. In KM, there is a misguided view that organizations and managers should always seek to transform tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. Contributing to this view has been Nonaka’s SECI model18 which is unfortunately accepted as a universal fact by many, despite serious criticisms19. To have sought to transform tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge in the Helidon Hills project would have been an inappropriate reductionist response in the face of complexity. Tacit knowledge is dynamic, involving multiple ever-changing and adapting sources and users of knowledge that are in a constant state of flux. This creates the space for ideas and ways forward to emerge. Trying to turn this tacit knowledge interplay into explicit knowledge kills the adaptive and emergent capacity. Most of the explicit knowledge that needed to exist in the Helidon Hills project already existed before the project: in-depth ecological surveys, resources studies, land use planning overlays etc. But that explicit knowledge will achieve little because sustainability happens through the decisions of a myriad of human decision-makers, and those decisions are primarily driven by tacit knowledge. The project acted to have that tacit knowledge better informed by explicit knowledge, but not the other way around because for ongoing success it’s vital to stay in the tacit knowledge space.

- Top-down vs. collaborative consensus. In KM, there is a view20 that in the face of complexity, “instead of attempting to impose a course of action, leaders must patiently allow the path forward to reveal itself.” However, as this Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills case study shows, there are some key actions that leaders can and should readily identify and impose before then patiently allowing the remaining path forward to reveal itself. In this case, these actions were that the nature conservation and cultural heritage values of the area must be protected as a non-negotiable given, and that landholder rights would be recognized and respected. A further example demonstrating the success of this layered decision-making approach in the face of complexity is China’s Loess Plateau recovery, where environmentally destructive grazing was banned on the fragile Loess landform while rural communities were then engaged in processes that enabled a new sustainability pathway to reveal itself. For further insights into this layered decision-making approach, see the RealKM Magazine article “Top-down vs. collaborative consensus: using the most appropriate approach for the decision-making level.”

- Inspiration. Just as the approach I took in coordinating the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills project had been inspired by my previous experiences, my experiences in this project in turn inspired me to further develop and apply similar approaches in numerous other environmental programs and projects. These case studies will be the subject of future articles in this series.

- Undemocratic power plays. Towards the end of the Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills project, the Queensland Government agency responsible for mining strongly objected to the high level of stakeholder ownership over decision-making processes. The agency did this in reaction to having had their desire for the entire Helidon Hills area to be declared a mining reserve rejected by nearly all other stakeholders. In response, project sponsor WESROC (see “Background” section above) sought to dismantle the community ownership through the appointment of a new project coordinator above me. I then took what I considered to be the only morally responsible action, which was to resign. As a Helidon Hills landholder discusses in the paper “The Human Factor in Biodiversity Conservation” on pages 38-39 of the Proceedings of the 2000 South-East Queensland Biodiversity Recovery Conference21, this action derailed WESROC and preserved the success of the project. Having learnt from this experience, I sought to try to prevent such undemocratic power plays from affecting future projects. However, as a future article in this series will reveal, I would later experience a far worse case of this, in which the actions of a very powerful individual in the media would destroy a project that would have both saved a now nearly extinct ecological community and provided significant community benefits.

Editor’s note: This article was first published on 29 October 2015 as “Case Study: Knowledge transfer and sharing through collaborative learning and governance.” It has been revised and updated for inclusion in the case studies in complexity series.

Header image source: Knowledge sharing in the Helidon Hills. © Bruce Boyes, CC BY-SA 4.0.

References:

- Google. (n.d.). Google Maps location 27°28’47.4″S 152°11’46.3″E. Retrieved 27 November 2023, from https://maps.app.goo.gl/wfnyfmtRzusEJR2DA. ↩

- Hill, K. D. (1999). A taxonomic revision of the white mahoganies, Eucalyptus series Acmenoideae (Myrtaceae). Telopea, 8(2), 219-247. ↩

- Boyes B., Pope, S., & Mortimer, M. (1999). Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Draft Management Plan December 1999, as amended by Sharon Boyle & Associates under direction of the Interim Management Group. Ipswich Queensland: Western Subregional Organisation of Councils (WESROC). ↩

- Megalogenis, G. (2010, September 24). A tale of two elections – One Nation and political protest. Queensland Historical Atlas. ↩

- Bean, C. (2000). Nationwide Electoral Support for One Nation in the 1998 Federal Election. In Leach, M., Stokes, G., & Ward, I. (eds.) The Rise and Fall of One Nation. St. Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press. ↩

- Reeve, I., Frost, L., Musgrave, W., & Stayner, R. (2002). Overview Report, Agriculture and Natural Resource Management in the Murray-Darling Basin: A Policy History and Analysis, Report to the Murray-Darling Basin Commission. Armidale NSW: Institute for Rural Futures, University of New England. ↩

- Moore, T. (2010, May 27). A green tax for green space? Brisbane Times. ↩

- Toowoomba Chronicle. (1998). Tension at Helidon meeting. Toowoomba Chronicle. ↩

- Preece, N. D. (2017, November 3). Australia among the world’s worst on biodiversity conservation. The Conversation. ↩

- Kemp, D., Fredericks, B., Muir, K., & Barnes, R. (2021, October 21). Fixing Australia’s shocking record of Indigenous heritage destruction: Juukan inquiry offers a way forward. The Conversation. ↩

- Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0. ↩

- Boyes B., Pope, S., & Mortimer, M. (1999). Sustainable Management of the Helidon Hills Draft Management Plan December 1999, as amended by Sharon Boyle & Associates under direction of the Interim Management Group. Ipswich Queensland: Western Subregional Organisation of Councils (WESROC). ↩

- Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, 85(11), 68. ↩

- Harding, R., Hendriks, C., & Faruqi, M. (2009). Environmental Decision-Making: Exploring complexity and context. Sydney: The Federation Press. ↩

- Jones, H. (2011). Taking responsibility for complexity: How implementation can achieve results in the face of complex problems. Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Working Paper 330. London: ODI. ↩

- Cummings, S., Regeer, B. J., Ho, W. W., & Zweekhorst, M. B. (2013). Proposing a fifth generation of knowledge management for development: investigating convergence between knowledge management for development and transdisciplinary research. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 9(2), 10-36. ↩

- Gatton, Lockyer and Brisbane Valley Star. (1999). Helidon Hills project co-ordinator ‘unties cord’. Gatton, Lockyer and Brisbane Valley Star. ↩

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14-37. ↩

- Gourlay, S., & Nurse, A. (2005). Flaws in the “engine” of knowledge creation. Challenges and Issues in Knowledge Management, 293-251. ↩

- Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007). A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, 85(11), 68. ↩

- Burkett, G. (2001). The Human Factor in Biodiversity Conservation. In B. R. Boyes (ed) (2001). Biodiversity Conservation “From Vision to Reality”, Proceedings of the 2000 South-East Queensland Biodiversity Recovery Conference (pp. 38-39). Forest Hill: Lockyer Watershed Management Association (LWMA) Inc. – Lockyer Landcare Group. ↩

Also published on Medium.