Guqin learning with knowledge management [Arts & culture in KM part 2]

This article is part 2 of a series exploring arts and culture in knowledge management.

The oldest cultural relics around the world can embody a process of knowledge management as well. In other words, the act of preserving heritage is entwined with knowledge management. Without its cultural context, the technique, the musicians, and their remarks, Guqin is merely a simple musical instrument. For me, learning to play Guqin is mainly a process to learn how to manage knowledge.

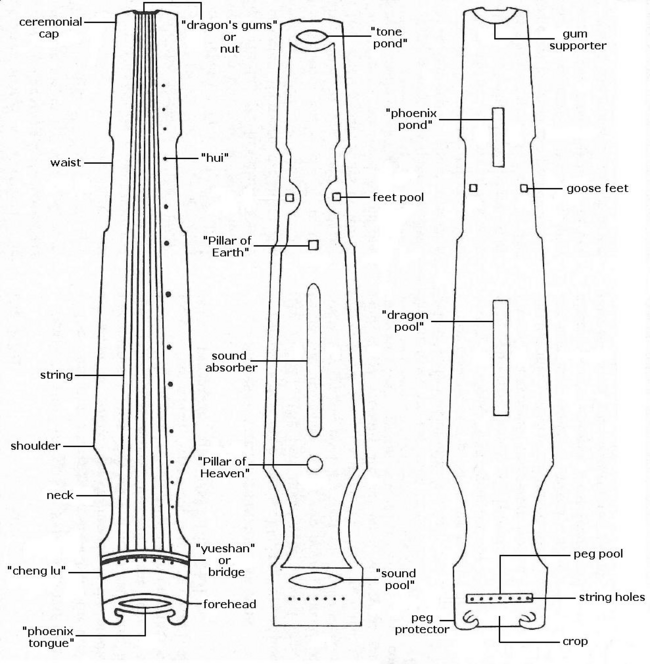

Guqin is the modern name for an ancient plucked musical instrument in China with seven strings. As an artistic heritage with thousands of years of history, Chinese believes that Guqin not only can play unsurpassed music but also tells stories about a unique culture, including ritual meanings and remarks of their users in different dynasties.

In the past, people first crafted Guqin with their knowledge and recorded their thoughts of aestheticism and philosophy during the musical performance, while musician in modern days, soon learned the knowledge through engaging with the instrument. For instance, a famous type of Guqin appearance called “Zhongni”, was named with Confucius’ courtesy name. Tradition has it that Confucius made his own Guqin into a special looking to express his courage to change the society for better ethics. Soon, Guqin with this distinctive appearance become well-known among Confucian scholars. Scholars showed their admiration on Confucius, attempted to learn his political ideology through Guqin performance, developing Confucianism through numerous generations. Guqin not only serves as a carrier of knowledge but also creates its own knowledge and culture over centuries.

While implementing the organization’s vision and mission, organizations also adjust strategies based on new knowledge and experience gained during the process. Similarly, in Hayes & Wheelwright’s matrix1, innovation creates new knowledge, and the same thing took place in the organization’s operation of existing knowledge.

When discussing how knowledge can be a strategic resource, the first thing to consider is to make knowledge accessible at the right place, delivered at the right time, presented in the right form, and obtained at the lowest possible costs. Such definition is applicable to Guqin beginners. On the surface of the Guqin, there are 13 white spots called “hui”, referring to standard pitch notes where players should press their fingers. To ensure that the fingers and the spots are aligned, the players must position the Guqin on stands with a special height or on their knees, and the proper distance between their bodies and the instruments are around two fists. Such posture is knowledge raised from previous experience, eliminating errors by using the player’s eyesight. In that case, it is feasible to find different pitches using their relative distances regardless of the player’s body shape, and furthermore, reducing the time costs in the learning. Moreover, organization applies knowledge in a strategic way to achieve the vision and the mission in the more effectively, efficiently, and productively.

Nowadays, Guqin players can produce tones without having prior knowledge and understanding of Guqin. Since in Earl’s perspective2, knowledge is a set of beliefs based on experience and could be defined along a continuum of thought, the process to access the knowledge can be described with the traditional Data-Information-Knowledge (DIK)3 knowledge hierarchy.

Each touch between the strings and the fingers creates distinct tones, and each tone is a transferring process for the raw data. Similar to data, separate tones are discrete and objective facts or observations, which are disorganized and unprocessed, containing no meaning or value. To create a melody, the player must combine the tones together in a harmonious way in order to make the melody flow smoothly. Through a similar process, raw data is interpreted, contextualized, corrected, condensed, and categorized. For knowledge management workers, it is important to classify raw data into specific clusters to manage data and select the right data for usage. This is also a practice of their data literacy skills. Ultimately, “data” becomes “information” and contains meaning, relevance, and purpose, while melodies composed of different notes hold values and develop into a meaningful piece of music to be memorized and recorded.

To fill in the gap from a line of melody to a real Guqin piece, the performer inputs own design then perform to others to test the output validity. During the composition of the famous Guqin masterpiece “Flowing Water”, the musician wants to express his observation about flowing water by applying different gestures to produce the rhythm of low pitches in order to mimic the sound of water hitting stones and falling from cliffs. The musician incidentally met a traveler who can completely understand his idea and appreciate his fertile imagination. In knowledge management, knowledge originates and gets applied to the mind of knowers, which consequently requires codification and application to a specific scenario to test its validity. In an organizational perspective, its culture must be fully understood by employees in order to motivate an individual’s commitment and willingness to practice the culture and start knowledge sharing in daily operations.

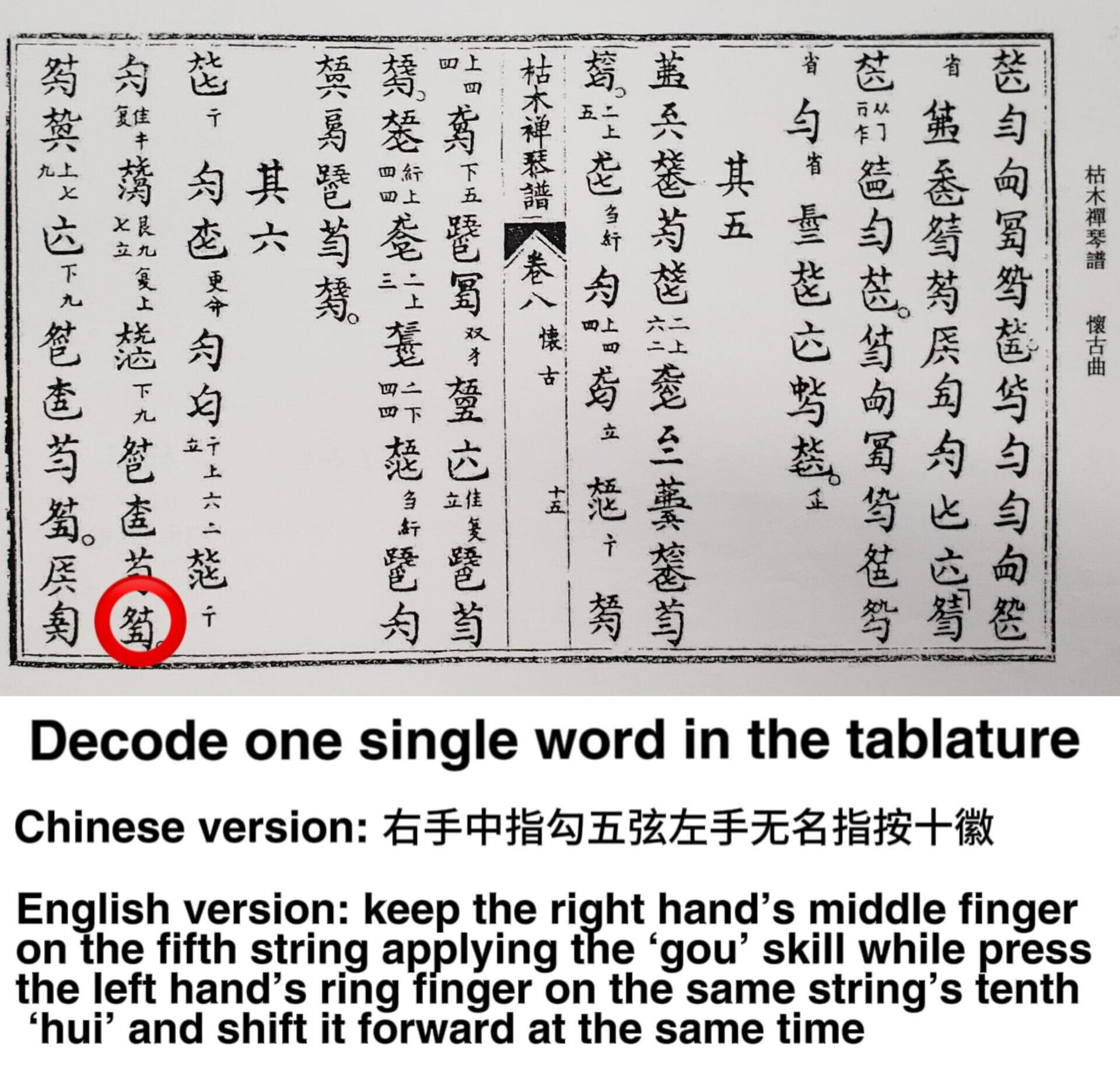

Mastering the hand-based techniques required to perform Guqin is essential, but the ability to recognize the historical masterpieces is equally important and challenging. The most common Guqin scores are in tablature form which record details including the finger gestures and the “hui” positions for every tone. This tablature score replaces sophisticated sentences of instructions with small element of Chinese characters as specialized notations. The tablature scores of Guqin pieces link modern learners with masters from ancient time as if we can directly visualize the techniques and skills they utilized. This process fulfills one of the codification principles, as knowledge managers should evaluate knowledge for usefulness and appropriateness for codification, suggesting the selection for the most valuable knowledge. For organizations, knowledge that needs to be acquired by employees is the most desirable but difficult to be transferred from tacit to explicit. For instance, the experience and knowledge gained from employee orientation and shadowing experienced employees are desirable for new employees.

However, in Nonaka’s statement of paradox4, knowledge that is easily codified must be hard to maintain its secrecy. Motivations and activities mentioned above can be extended beyond workplace. In that case, a comfortable lounge outside the office that provides employees with a space to socialize and communicate is important to solve dilemmas.

During the learning process of Guqin, once we have confidence for the knowledge about the music pieces and our skills, we can participate in “yaji”, which means an elegant gathering. In such event, performers in different skill levels and backgrounds gather in an informal setting to promote and play “qin” music. It is often a good opportunity to network, ask questions, and learn from the answers, during which the knowledge gets transferred from one to another.

Similarly, Nonaka and Konno5 emphasized the importance of a shared place and introduced the definition of ‘Ba’ for embedded knowledge. Based on our earlier analysis of the importance and effective outcome of knowledge sharing, organizations are encouraged to provide a safe and separate space for employees to organize their elegant or exciting coffee/tea gathering. A ‘Ba’ can cultivate new relationships, enhance brainstorming for new projects, and develop organizational culture and identity among employees. For organizations, the more they learn from others, the less risky the organizations are when facing accidents and challenges like unpredictable turnover or job transitions.

Guqin learning is an ancient subject while knowledge management is a new subject. Nonetheless, these two different subjects share intrinsic values in knowledge sharing and transfer. For organizations in the modern society, the approaches they decide to take could potentially be adopted from these ancient people, inheritors, and innovators in order to achieve sustainability.

Article source: Adapted from Guqin Learning with Knowledge Management, prepared as part of the requirements for completion of course KM6304 Knowledge Management Strategies and Policies in the Nanyang Technological University Singapore Master of Science in Knowledge Management (KM).

Header image source: DongDj.Com.

References:

- Hayes, R. H., & Wheelwright, S. C. (1979). Link Manufacturing Process and Product Life Cycles. Harvard Business Review. ↩

- Earl, M. J. (1997). Knowledge as Strategy: Reflections on Skandia International and Shorko Films. In L. Prusak (Ed) Knowledge in Organizations, 1-15. Newton, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann. ↩

- Ackoff, R. L. (1989). From Data to Wisdom. Journal of Applied Systems Analysis, 16, 3-9. ↩

- Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (2007). The Knowledge-Creating Company. Harvard Business Review, 85(7/8), 162. ↩

- Nonaka, I., & Konno, N. (1998). The Concept of “Ba”: Building a Foundation for Knowledge Creation. California Management Review, 40(3), 40-54. ↩