Knowledge management in Model United Nations

Model United Nations1 (MUN) is an academic simulation of the United Nations. During MUN conferences2, students take on the role of ambassadors of different countries and debate, negotiate and tackle the actual agenda topics currently or previously being addressed at the United Nations. Hundreds of thousands of students worldwide take part every year at all educational levels. In fact, I used to be one of them.

Looking back on my university days, Model United Nations activities are the most colorful part of them. I have participated in different MUN conferences in various roles including delegate of regular committees and Main Press Center, Dais Member, Dais Head, member of Organization Committee, Secretary General, etc. This experience has given me different insights into international relations and precious friends in my life.

As an academic simulation activity, sometimes even used as an experiential learning method, MUN requires not only great enthusiasm but also a wealth of knowledge. That’s why knowledge management (KM) exists and is significant in every process of MUN conferences.

MUN: a student-centered community of practice

Wenger advises3 that “Communities of practice develop around things that matter to people.” Although not from the same organization, MUNers do this. They come together in 3-5 day sessions, and learn, discuss, share, cooperate and even argue with each other to solve global challenges.

Their discussions are not limited to the speeches and caucuses at the conference (as in the case of the United Nations General Assembly), but the pre-session preparation, tea breaks, and social events are all good times for exchange. Some of the discussions start even before they meet. Similarly, knowledge is transferred between them in various forms such as statements, pages, working papers, draft solutions, etc.

As the MUN conference came to an end, so did this student-centered community of practice. Another MUN conference is a new beginning. In a sense, I see it as a community of practice with a fluid nature that allows students to gain stronger knowledge and richer communication opportunities.

Academic “cosplay”: active knowledge acquisition and creation

One of the crucial elements of the MUN conference is the sense of immersion which is the key to more active knowledge acquisition and creation4.

When you’re a student, serious and integrated knowledge of international relations can be boring. But assuming you’re a diplomat, things are completely different. It is important that you have to know as comprehensive as possible about the economic, political, and cultural aspects of the country you are a delegate of in order to react appropriately at international conferences. After all, behind diplomats there are national interests and the people of a country.

What motivates students in such an academic role-play is therefore curiosity and responsibility. When they mine for knowledge and construct their own knowledge maps with critical thinking, both knowledge acquisition and knowledge creation are more interesting than in traditional educational approaches.

Furthermore, in order to avoid making ridiculous statements at the MUN conference, student delegates find ways to verify information and ask for confirmation. They have to make the journey from information to knowledge themselves, which is a very rewarding process of building their own KM system.

Conflict: effective knowledge sharing

Cooperating and conflicting are known to be two important forms of international relations, and the same goes for MUN. In MUN conferences, participants share knowledge anytime and anywhere. One of the interesting things I found when reflecting back on my MUN experience is that conflict often promotes knowledge sharing.

Let’s get to the real scene.

It was my first MUN conference, the committee was the UN Security Council and the issue was Threats to International Peace and Security Caused by Terrorist Acts (ISIL). When discussing the efforts to counter the threats, the use of the word “ISIS” by the delegate from Egypt was strongly protested by the delegate from the United States.

The delegate from the United States insisted that “ISIL” was the more appropriate term because the name “ISIS” first belonged to a goddess before it was used by a terrorist organization and was then preferred by many women. He argued that it was offensive to Western women to use ISIS to describe a terrorist organization (deliberately omitting geopolitical considerations, of course). It is also true that many women whose name is Isis are outraged and have collectively petitioned the media to use the term “ISIL”.

This conflict involves cultural differences, political positions, geopolitical relations, and many other issues. In this case, all participants are brought into the scenario to think about unnoticed issues and the knowledge sharing becomes effective and memorable.

Draft solution: knowledge application and retention

At the end of the meeting, delegates are asked to submit draft resolutions and to vote on them in a plenary session to decide whether or not to adopt them. Throughout the conference, they must debate, consult, persuade and even compromise to ensure the final adoption of the draft resolution.

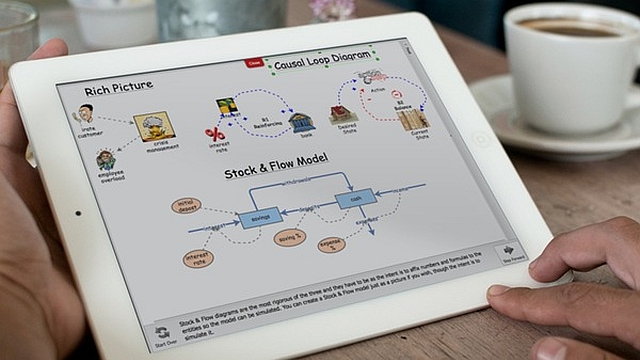

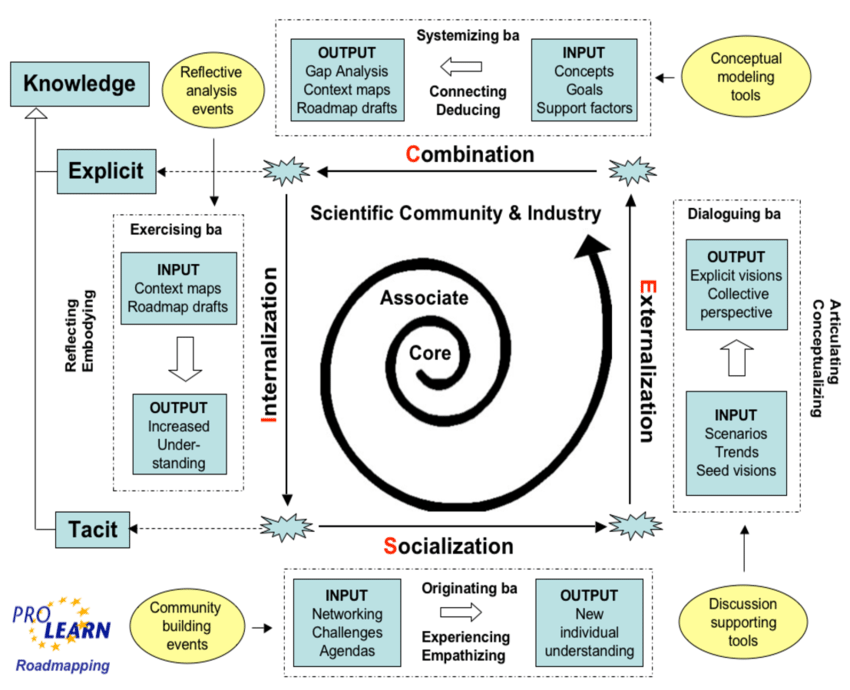

In the process, they receive perspectives from others and develop tacit knowledge of communication skills, negotiation skills, etc. during the caucus, which they internalize as they participate in the resolution. In a way, this is also an application of the SECI model5. MUN conference becomes an excellent “Ba,” similar to what is shown in the following diagram.

The future: sustainable knowledge

As our lecturer Rajesh Dhillon advises, sustainable knowledge is of paramount importance in the context of MUN for a number of reasons.

Firstly, MUN is an academic simulation that requires students (our future leaders) to delve deep into various aspects of international relations, and this knowledge needs to be sustainable to support ongoing participation and learning within the MUN community. As students engage in multiple MUN conferences and even mentor others, the knowledge they accumulate becomes a valuable resource for the entire community. Sustainable knowledge ensures that this resource remains accessible and relevant over time, benefiting current and future participants.

Moreover, sustainability in KM within the MUN community fosters a culture of continuous learning and improvement. It encourages students to not only acquire knowledge but also to refine their critical thinking, research, and communication skills. Sustainable knowledge supports the development of informed and responsible global citizens who can tackle complex issues both within and outside the MUN context.

A lasting reflection: knowledge and KM

Finally, I would like to end with a question-and-answer session.

At one of the MUN conferences I attended, the then Chinese Ambassador and Senior Official of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) Xie Bohua was invited to be the guest of honor at the opening ceremony. My senior asked him a question. “Perhaps most of us will not be involved in diplomatic work in the future. What can we do if we are still passionate about international relations?”

And his answer struck me.

He said: “Whatever you try to do well in your field will be the backbone of diplomacy.”

I think it is the same with knowledge and KM.

Wherever and whenever you acquire it, whether it seems useful or not, knowledge and KM methods will be part of the strength of our life.

Article source: Adapted from Knowledge Management in Model United Nations, prepared as part of the requirements for completion of course KM6304 Knowledge Management Strategies and Policies in the Nanyang Technological University Singapore Master of Science in Knowledge Management (KM).

Header image source: Casey C, Amador Valley Today.

References:

- United Nations. (n.d.). Model United Nations. Retrieved from https://realkm.com/go/model-united-nations/. ↩

- Phillips, M. J., & Muldoon Jr, J. P. (1996). The Model United Nations: A strategy for enhancing global business education. Journal of Education for Business, 71(3), 142-146. ↩

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning as a social system. Systems thinker, 9(5), 2-3. ↩

- Calossi, E., & Coticchia, F. (2018). Students’ knowledge and perceptions of international relations and the ‘Model United Nations’: An empirical analysis. Acta Politica, 53, 409-428. ↩

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14-37. ↩

- Kamtsiou, V., Naeve, A., Kravcik, M., Burgos, D., Zimmermann, V., Klamma, R., Chatti, M., Lefrere, P., Dang, J., & Koskinen, T. (2007). Gap Analysis Report. Research report of the ProLearn Network of Excellence (IST 507310), Deliverable 12.12. 2007. ↩